2024 marks the twentieth anniversary of the passing of Fausto Romitelli, an innovative composer whose music continues to surprise with its ability to transcend academia and traditional forms, going beyond the classical concept of composition. His premature death left many of his works unexplored; it took years of research to discover new pieces, give them structure, and fully understand their history.Particularly significant is his catalog for guitar, an instrument that played a central role in his early studies and would become a guiding line in his compositional style. After years of experience in contemporary music, Elena Casoli decided to open the archives and, in collaboration with the Giorgio Cini Foundation and the Stradivarius label, released Solare, the first monographic album dedicated to the Friulian composer. We interviewed her to delve into the steps that led her to this important decision.

Elena, thank you for accepting our invitation. I’d like to start with your recent concert on April 26th at the Musikhochschule in Lübeck. You presented a unique program, giving the audience the opportunity to discover a piece by Fausto Romitelli, Étude pour Bilitis. Could you tell us more about it?

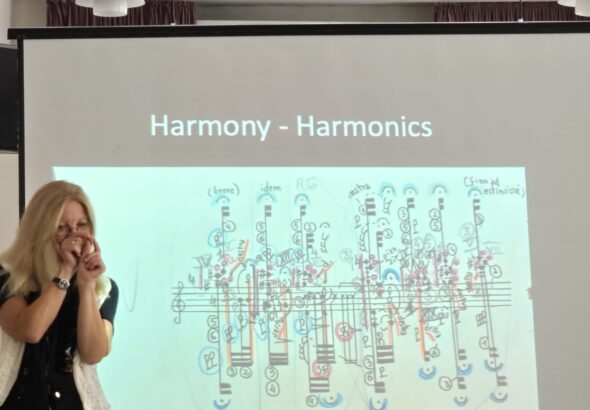

It all started with an invitation from Otto Tolonen to the Musikhochschule in Lübeck, in collaboration with Oliver Korte, a musicologist, and also made possible thanks to the support of the Hochschule der Künste in Bern.The project included a masterclass led by me, followed by a lecture on Étude pour Bilitis and, in conclusion, a concert with a program almost entirely dedicated to Fausto Romitelli’s guitar music, concluding with Poèmes de la Mort by Frank Martin in a rare performance by students from the Hochschule in Lübeck. For the concert, I involved two students from the Hochschule der Künste in Bern – Maria Criscione and Samuele Provenzi – so we were able to present to the Lübeck audience five works for guitar by Fausto Romitelli: Highway to Hell, La Lune et les Eaux, Solare, Étude pour Bilitis, and Trash TV Trance.

I focused on Solare and the modern premiere of Étude pour Bilitis – a term we agreed on with the Music Archive of the Giorgio Cini Foundation, since there is no record of a first performance at the time of composition –.

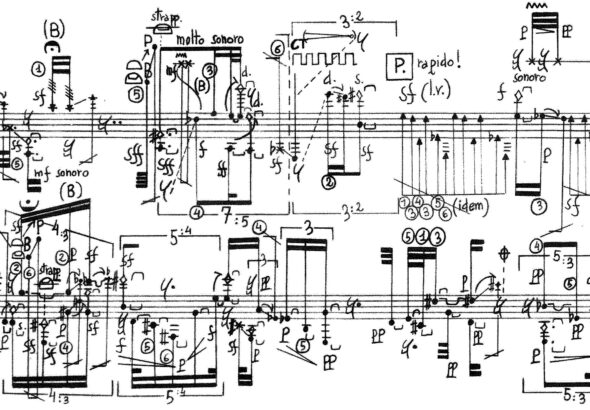

Being a piece from 1983, we are talking about a composer who was just in his twenties, a student at the Conservatory of Milan, who was beginning to explore spectralism and was still searching for a well-defined style. The characteristic of his early works, such as Solare or Coralli, is precisely the density of each sound, the layering of every gesture, almost as if wanting to transcend the limits of the instrument. How was it for you to approach Étude pour Bilitis from this point of view? Did you encounter any particular difficulties?

Just a few days ago, with Francisco Rocca, a musicologist who has been working at the Musical Archive of the Giorgio Cini Foundation for years, we were trying to remember when he first told me about the unpublished score of Étude pour Bilitis. We believe it was in 2017, and then, during one of my workshops at the Foundation in 2018, I received a copy of the score. At a first reading, and then in the following months, Étude pour Bilitis presented itself from the very first figures as a piece with intriguing, elaborate sonorities. As I start to work on it, I encountered more and more combinations of harmonic sounds and unusually original resonances. But in many parts, the congestion and extreme overlap of gestures, resonances, and sound materials seemed almost unachievable. I was certainly still surprised at how complex his sonic imagination for the guitar was even at twenty, in some ways with an even more unrestrained intuition in this piece than in Solare and Coralli. I began a long, slow process, coming closer to and distancing myself from Étude pour Bilitis several times. I thought that six strings might not be enough, and it might need a version for two guitars to achieve all the textures, especially the simultaneous glissandi with both hands and the contrary motion along the fingerboard. Then I let myself be guided by the sound, which had been the first reason for my fascination and interest. I also sought out the figure of Bilitis, through Les Chansons pour Bilitis by Pierre Louÿs, Claude Debussy, and his musical version of the Chansons pour Bilitis, a chain of encounters that helped me understand. Just as archaeologists listen to and read stones, I investigated the past and possible sources of inspiration for the composer, searching for answers and finding my way in the sound and vitality of the gesture. Performing it in concert at the Kammermusik Saal in Lübeck, crowded with an audience, was for me a confirmation of the quality and communicative power of this piece. For now, it remains a research work that has not been published and is part of the collaboration with the Giorgio Cini Foundation and Francisco Rocca. Perhaps in the coming months, there will be an opportunity to hear it online, and I hope that in the coming years, it will enrich our repertoire.

In 2018, Stradivarius released first monographic work dedicated to his guitar music. Where did the idea come from?

It certainly wasn’t the first time that Stradivarius supported monographic projects dedicated to contemporary composers, but this one had the particularity of presenting four works in their world premiere recordings. We were fortunate enough to record with Andrea Dandolo as the Tonmeister, with whom – thanks to his experience with this repertoire and a deep understanding of the guitar – we were able to work on the sound capture, both traditional and with the preparations in La Lune et les Eaux and the live electronics in Seascape, aiming for a result that fully convinced us.

Was the choice of the tracklist difficult? Why did you decide to exclude Étude pour Bilitis?

Roberto Elli from Stradivarius – who, as a music producer, has supported and passionately dedicated organizational energies and financial resources to New Music – was interested in producing a monographic CD of Romitelli’s music for guitar.

I already had Solare, Coralli, Highway to Hell, and La Lune et les Eaux in my repertoire, which I had presented in duo with Jürgen Ruck at Dampfzentrale in Bern, I think in 2009, and later with Virginia Arancio at the MilanoMusica Festival dedicated to Fausto Romitelli in 2014. I asked Virginia Arancio to also record Trash TV Trance and, in duo with the recorder player Teresa Hackel, Simmetria d’Oggetti, a work that they had already performed publicly many times. Thanks to Teresa Hackel’s presence, we also took the opportunity to complete the album with Seascape, another important piece from that compositional phase of Romitelli, which Teresa already had in her repertoire.

The piece that gives the album its title, Solare, immediately highlights the search for an “electric” sound, very far from what one would expect from a classical guitar. Was this perhaps just the first step towards the relationship he would later develop with the electric guitar? Yet, in many parts, a certain lyricism emerges, a choice of light sounds and subtle dynamics. Is this what distinguishes it from Coralli, a piece that is decidedly more energetic and nervous?

When I received the Solare score from Fausto Romitelli, the aspect I found most complex at that time was the layering of events, the stratification of parallel events, which in some sections is really very dense. I can imagine that even back then Fausto had the desire to write for the electric guitar – this is also evidenced by the quantity and quality of his vinyl and CDs stored in the Romitelli Archive at the Giorgio Cini Foundation – but in those years there were still few performers who could read such a complex score and were also experienced electric guitarists.

The use of bending, double glissando on 4th-string dyads, and the “distortion” of sound produced through various finger interventions on the string with extreme dynamics in F and FF can be seen as signs that he was seeking the sound and gestures of the electric guitar in the classical guitar.

The melodic lyricism in this music, however, is a constant that, in my opinion, goes beyond the electric guitar and rather belongs to Fausto’s ability and need to express himself through the singing of a line. Among the pieces for classical guitar, Solare is undoubtedly the one in which the lyricism is most intense, and I would say that it is the guiding thread throughout the piece, from the opening tremolo to the final vocal line.

La Lune et les Eaux marked an important turning point in Fausto Romitelli’s style. For the first time, the use of preparations on instruments and the inclusion of everyday objects become central components of the composition. This piece, which you recorded with Virginia Arancio, represents a more mature work, written by a Romitelli who was approaching thirty, just before leaving Milan to move to Paris. What challenges and new perspectives arise for an interpreter when facing this language compared to the solo guitar works?

It’s a piece that still surprises me when I play or teach it, because of how Romitelli was able to “bend” the sound of the guitars through the preparations to fit his compositional imagination. He transformed the performers into a sort of “sound and instrumental mechanisms,” which remind me, in their movement, of the mobile and asymmetric sculptures of Jean Tinguely.

And here, too, the stratification in layers creates a refined sequence, dense with combinations, from the inexorable rhythmic progression to the next transformation/preparation. With each page, the two guitars together become another instrument, but at the same time, the piece maintains a stable and solid structural coherence. It requires precise teamwork, which then transforms into sounds that are at times unstable/evanescent, only to become mechanical/metallic/material. As interpreters, it’s a virtuosity and a pleasure to follow Romitelli’s visionary thought in this piece.

Teresa Hackel, an interpreter alongside Virginia Arancio of Simmetria d’oggetti, also recorded Seascape, a piece for solo flute: a singular and interesting choice. Why include a non-guitar piece in the collection?

Seascape was written in 1994, but we can think that it shares many connections in the form of musical gesture with the compositional phase of these works for guitar, particularly Coralli and La Lune et les Eaux. Seascape was written for Antonio Politano – a flutist with whom I played in duo for several years. In a larger ensemble, Antonio and I had performed for a project called Symphonie Diagonale, organized by Paolo Pachini, in which there was also a work by Fausto Romitelli written for the film by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy Ein Lichtspiel, schwatz-weiss-grau.

The composition of this work is from the late 90s, and it combines guitar and Paetzold recorder in musical figures that belong to both Simmetria d’Oggetti and Seascape. So it’s as if a dense network of underground connections led to this choice.

Arriving at the crucial point of Fausto Romitelli’s guitar repertoire: Trash TV Trance. There has been much discussion about this piece: perhaps a point of arrival, or a starting point, if we consider the later masterpieces like An Index of Metals and Dead City Radio – Audiodrome. It is a piece that reinterprets the electric guitar’s practice extensively and requires much experience. How should a guitarist approach this composition?

I believe the uniqueness of Trash TV Trance is tied to two factors: an urgent expressive need of Fausto Romitelli, which runs through the poetics of all his later compositions – an urgency in terms of time and the intensity of experiences he lived in those years – combined with a compositional maturity that guides his writing with confidence and a clear vision of the result he aims to achieve. It’s a piece with strong inspiration, authentic in every gesture.

I believe there is not a single moment in Trash TV Trance that is not absolutely “necessary” for the composer. As in the earlier works for guitar, we find three fundamental elements of his writing: the layers – here even more acrobatic and multiplied by the loop machine – the lyricism – which pervades the entire piece and is not just in the reference to Pink Floyd – and the precise, detailed writing, rich in details for every aspect of the instrumental gesture – from the use of objects to the temporal mechanism in which the gesture is completed.

The indicated metronomes are important for grasping his thinking and the elasticity of the marks on the page. The physical characteristics of the objects used are not easily modifiable without sacrificing the timbral and gestural result. The careful performance notes created by Tom Pawels will always remain a starting point and reference, despite the continuous transformation of the electric guitar’s sound equipment and future performers’ tastes.

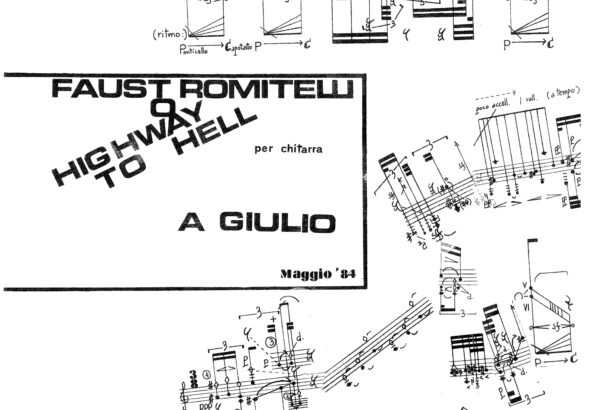

The elaboration of Fausto Romitelli’s musical catalog has brought to light new works and texts that had never been examined before. This is the case with Highway to Hell, an unpublished piece that, in collaboration with the Cini Foundation, you discovered and decided to publish. A complex responsibility, as the piece does not include any performance notes. What have been the most difficult decisions to make from an interpretative point of view?

Highway to Hell is an unsolved puzzle. After extensive research by myself and Francisco Rocca, it has not been possible to find any performance notes or indication that explains the meaning of the letters and the relationship between the “Percorso” and the other material arranged freely like a collage on the page. We know that the piece is dedicated to Giulio Chiandetti, a guitarist from Gorizia and a friend of Fausto’s, but even Giulio could not give us a key to interpretation.

So, if we want to perform it, we take responsibility for its form and the organization of the material, while still seeking the right timbre and respecting every detail of the writing. My vision is that there is a dialectical and tense relationship between the more traditional material of the Percorso and the more experimental material of the collage, fragmented throughout the rest of the page, whose arrangement resembles Serenata per un satellite by Maderna. The “collage” opens up a new vision of the guitar, of sound, and of instrumental gesture, which Romitelli later developed in his other works for guitar.

Therefore, I would say that in order to find one’s own interpretative key for Highway to Hell, it is even more important to know Romitelli’s poetics and the other works from that period.

What was your relationship with Fausto Romitelli like? When did you meet? Did you ever have the chance to work together?

We met at the Conservatory in Milan, where we studied in the same years. We worked together for the Symphonie Diagonale project and then we would meet at concerts, until Fausto moved to Paris. We stayed in touch through letters for Solare, although I performed it in public much later. I remember Fausto’s energy and his loud energetic laughter at a dinner after concert. I remember him as a sunny, positive young composer, full of energy. The news of his illness and his premature passing left us shocked, sadly surprised that something like that could happen to a composer of our generation in the prime of his artistic vitality.

Twenty years after his passing, what do you think of his musical legacy? Which aspects of his work continue to surprise and inspire composers of the current generations?

It’s not easy to answer this question. There are several pieces for solo electric guitar in which you can feel the influence of Trash TV Trance, just as An Index of Metal opened a new phase of multimedia work in the electronic/experimental field, which was then taken up and developed in the following years. The psychedelic, at times magmatic sonorities of his last works created new links between different musical worlds, worlds that today interact with greater freedom and ease, perhaps also thanks to Romitelli’s work. I believe that the dramatic appeal and interest in his later electronic works have sometimes overshadowed his earlier pieces, which instead deserve to be performed and listened to for their timbral richness, the wonder of the gesture, and the light that animates them. As he writes in the score, his poetics from those years sought a “vibrant, luminous” sound!