TEXTS READ IN WATER

After contextualizing the words used by the composer himself to present his piece, let us focus on one of the first distinctive features that Audéeis presents in comparison to its predecessor, Artemis: its title. While Artemis is clearly a homage to the eponymous quartet to which the work is dedicated, in Audéeis, the meaning of the Greek term sheds light on the Madrid composer’s intentions for this second version featuring a cantaor. As Frank Haase indicates in his text centered on Hesiod and Plato, audéeis refers to the ‘human discourse’ granted by the gods to materialize their divine voice on Earth, making it audible.1 It can therefore be deduced that the human voice of the cantaor and its projection through the use of the cajón in the rhythmic section of Audéeis are human manifestations of the “imagined flamenco voice” and the “virtual percussion instrument” entrusted to the string quartet in Artemis.2 Another textual individuality found in Audéeis is the use of traditional flamenco lyrics juxtaposed3 with poems by Valente: the texts sung by the cantaor throughout the work. Some of the melodies of these texts had already ‘appeared’—albeit exclusively instrumentally (without consonantal traces)—in the string quartet version of Artemis, while other texts—such as the two poems by José Ángel Valente—were later added to the ‘almost’ unchanged structure of the quartet, thus creating a kind of palimpsest.4

At the beginning of the score, the texts used in the cantaor’s section are collected and presented alongside their sources. This information is then supplemented with its English translation:

MARTINETE Y TONÁ, popular

Yo soy un pozo de fatigas

que un buen manantial tenía

ay a la par que crece el agua

van creciendo mis fatigas.

Aquel que tiene tres viñas

(y el pueblo le quita dos)

que se conforme con una

y le de gracias a Dios.

BULERÍA, popular

La hierbabuena regarla

la que no esté de recibo

con la manita apartala.

SIGUIRIYA, popular

Si a caso me muero

pago con la vida.

JOSÉ ÁNGEL VALENTE, 1995

Si cortamos el tronco del cerezo

no hallaremos las flores en él:

la primavera sola tiene

la semilla del florecer.

JOSÉ ÁNGEL VALENTE, 25. V. 2000

Cima del canto.

El ruiseñor y tú

ya sois lo mismo.

MARTINETE AND TONÁ, popular

I am a well of hardships that

once had a good spring.

Ay, as the water rises,

my hardships rise too.

He who has three vineyards

(and the people take two),

let him be content with one

and give thanks to God.

BULERÍA, popular

Water the gentle mint;

that which is not decent,

with your little hand, set it aside.

SIGUIRIYA, popular

If I die,

I will pay with my life.

JOSÉ ÁNGEL VALENTE, 1995

If we were to cut the cherry tree’s trunk,

we would not find flowers inside:

spring alone holds

the seed of blossoming.

JOSÉ ÁNGEL VALENTE, 25. V. 2000

Summit of song.

The nightingale and you

are now the same.

Both poems belong to the final phase of the Spanish poet’s production, included in his poetry collection Fragmentos de un libro futuro,5 which comprises poems written from 1991 until his death in 2000. The first of the two poems used corresponds to Koan del árbol, 1996 version,6 while the second poem, with which Sotelo concludes the final intervention of the cantaor in Audéeis, is the last known documented poem written by Valente, Anónimo: versión,7 from the year 2000.

The juxtaposition of traditional flamenco lyrics with the poems of José Ángel Valente is justified as a result of the fermentation that constitutes Sotelo’s sonic ocean, as well as the poet’s own interest in this tradition.8 Lastly, it is worth mentioning that the source text is slightly modified by Sotelo during its adaptation to cante flamenco, articulating Valente’s verses with some Quejíos (‘vocalic spaces’—melismas—on the interjection ‘ay’) or performing repetitions to ‘respect’ the structure of traditional stanzas, as can be observed in the final repetition of Cima del canto:

Cima del canto ay cima del canto

el ruiseñor y tú ay ya sois lo mismo

Cima del canto ay cima del canto

In addition to these texts, which constitute the cantaor’s melodies, Sotelo permeates his score with various textual indications that, while sometimes strictly technical, at other times reveal the poetics of his sonic ocean, even serving as ‘signposts’ marking the poetic path of the work. Within the pages of Audéeis, Sotelo’s native Spanish coexists with the Italian of his master and the German of his Vienna study years. Curiously, there is a single instance of French, which, as mentioned earlier, might refer to some verses by Valéry,9 as well as a few brief appearances of Indian syllables, included for the requirements of traditional Indian music.10 Regarding the English used in the legend, it can be said that this was purely a practical choice.

Returning to the coexistence of the three languages in question, despite their seemingly chaotic succession throughout the work, there is a certain logic justifying Sotelo’s choice as an alternative to unifying all indications under a single language. References to flamenco tradition are made in Spanish, while technical instructions addressed to the performers (with few exceptions) are in Italian. Toná (p. 9, b. 63), Bulería (p. 29, b. 235), and Seguiriya11 serve as ‘signposts’ guiding us along the poetic path, just as the phrase canto hondo12 frequently appears alongside the string quartet’s instruments. Flamenco-specific terms like cantaor and cajón also find their place in the work’s pages, even going so far as to indicate the name of the performer for whom the flamenco percussion and cante parts were conceived: Arcángel.13

In Italian, in addition to purely technical instructions such as “con variazioni, cambia timbro, colori sempre diversi” (p. 29, b. 246), “Cello con la voce… come percussione” (p. 45, b. 413), “improvvisativo / ben ritmico” (p. 45, b. 417), we also find more rhetorical ones such as suono ombra (p. 9, b. 63), appassionato (p. 22, b. 149), or suono cristallo (p. 55, b. 507), which engage the performers’ imagination to enrich their musical interpretation.

The use of German—beyond a few technical indications accompanying those in Italian— 14is more enigmatic and therefore relevant to the analysis. Most German annotations are rhetorical in nature: wellenartig (p. 2, b. 14: undulating, wave-like), geheimnisvoll (p. 45, b. 413: mysterious, secretive), or nachdenklich (p. 59, b. 537: pensive, contemplative). If we add to these the few technical indications not appearing in Italian throughout the piece: leichte Akzente (p. 25, b. 179: light accents) and pizz. ‘Hindu’ (p. 25, b. 179: pizz. ‘Indian’), we find some clues confirming the direct link between Artemis (and consequently Audéeis) and Chalan, the 2003 orchestral piece in which Sotelo delved into traditional Indian music. As we will see later, some passages of Artemis and Audéeis are adaptations of certain sections of Chalan, adjusted for a chamber ensemble.

These textual clues allow us to find further connections between the work under examination and other pieces in Sotelo’s oeuvre. For instance, the cantaor’s first intervention is accompanied by the German indication mikro (p. 9, b. 67), an annotation already used in the violin piece composed a year earlier, where it appears more fully: “Die Mikro-Intervalle werden immer leicht hervor-gehoben” (Micro-intervals always slightly emphasized). When comparing the cantaor’s melody in this passage of Audéeis with the opening line of Estremecido por el viento for solo violin, one finds that both are identical.

The point at which the highest number of works converge is marked by the Italian indication ricorda! (p. 28, b. 233). This passage had already appeared in the first string quartet Degli eroici furori (2001), as well as in the two 2003 works previously mentioned: Estremecido por el viento (for solo violin) and Chalan (for orchestra), and again in Artemis and Audéeis—a sort of musical crossroads where these five works share a common point or memory. On the other hand, in the case of the indication suono cristallo (p. 55, b. 507), we find a connection at the timbral level between Audéeis and Si después de morir…,15 a work for cantaor and orchestra based on a poem of the same name by José Ángel Valente, completed in 2000 and dedicated to the poet’s memory after his passing that same year. Curiously, in the score of Artemis, this rhetorical nuance does not appear, even though it is an identical passage to the one in Audéeis. However, as previously mentioned, Valente’s poems were added later in Audéeis as a palimpsest upon the foundation of Artemis, manifesting Valente’s presence in the new version, and from which Sotelo seems to want to clarify—through a ‘simple’ indication—that the ‘crystal-like’ timbre used here is in some way linked to one of the most significant works of his relationship with Valente.

Tuesday, August 31, 2004

“We could speak of an attempt to create a new musical instrument based on an ancient musical practice: Flamenco. […] A string quartet that becomes an imagined flamenco voice, as well as a virtual percussion instrument.”16

SONORITY READ IN WATER

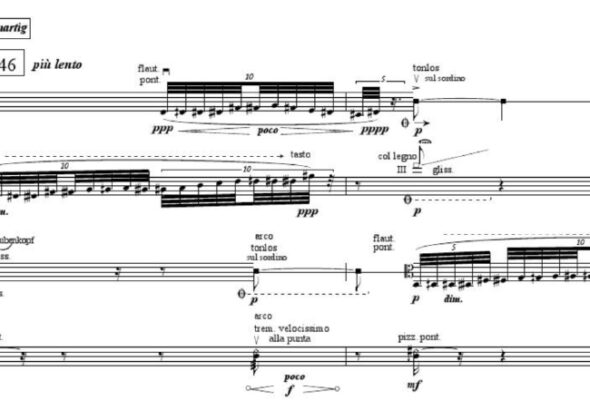

The “imagined flamenco voice” and the “virtual percussion instrument” created by Sotelo in Artemis materialize in Audéeis through the incorporation of the cantaor and his cajón. The idea of using the quartet—later adding the voice—as a synthesis, as a set of components of the same whole, is reflected in the sonority of the work, particularly through the use of heterophony.17 This structure, one of the most characteristic of the piece, is especially prominent in the creation of the “imagined flamenco voice,” which in Audéeis becomes the shadow of Arcángel’s voice. To observe the recreation of the “imagined voice” for the quartet and its subsequent concretization into the cantaor’s textualized voice, compare the same heterophonic passage in Artemis (p. 10, b. 70 and following) and Audéeis (p. 10, b. 70 and following). In Audéeis, the viola part is identical to that of the cantaor. The strict unison generates a new timbre and facilitates a more homogeneous synthesis with the rest of the quartet. The cello supports the main line an octave below, maintaining it for most of the time. However, at times, it presents certain ‘simplifications’ where it remains ‘static,’ acting as a sort of resonance that blurs—enriches—the final result. On a more ‘distant’ plane, the two violins act as a crystalline shadow—simplified by omitting the microtonal grace notes—constituted by ‘reflections’ of the main line in the high register18 and always on the ponticello (a timbre previously specified along with the rhetorical indication suono ombra, p. 8, bb. 56-59). In the most melismatic areas of the ‘vocal space’—see the septuplet or quintuplet in measure 71—the tremolo articulation is added to both instruments to help blur their contours, generating a timbral sensation reminiscent of a mirage.

Regarding the “virtual percussion instrument” and its subsequent materialization into the cantaor’s cajón, compare the same passage in Artemis (p. 26, b. 257 and following) and Audéeis (p. 30, b. 255 and following) to examine how a somewhat free hochetus19—developed in the quartet ‘without sound’—becomes the ‘spatialized veil’ of the continuum entrusted to the cajón in Audéeis. The free hochetus, in which the quartet’s instruments alternate—sometimes with slight overlaps—as if they were different parts of the same meta-percussion instrument, adheres to the new percussion layer that extends throughout the percussive section of the piece at the hands of the flamenco cajón. This new layer functions as a palimpsest, redefining the initial structure and providing the ensemble with a certain stability. Following this additional percussive line, we arrive at the use of las palmas (hand clapping)—with clear flamenco connotations—which replace the cajón (p. 32, b. 285) before finally flowing into the voice of the cantaor (p. 34, b. 306). This naked voice, presented without the previous heterophonic20 work, once again redefines the structures of Artemis that are reworked in Audéeis, constituting in this case a new section in which a sort of cante (melody) accompanied becomes the protagonist.

Another example of a redefined structure—and thus another individuality that Audéeis presents in comparison to Artemis—occurs towards the end of the piece in the passage Sotelo calls “resonance of what was once a vibrant voice.” In Audéeis, this vibrant voice overlaps with the work assigned to the string quartet in Artemis, now materializing in Arcángel’s cante. At this moment, the last two texts of the work appear: the siguiriya and the final poem by José Ángel Valente. In this case, the palimpsest generates a dialogue between the first and second versions, that is, between the ‘echoes’ of what was “a [previously absent in Artemis] vibrant voice” and Arcángel’s final interventions. This creates a structure of discant between the cantaor and the first violin, accompanied by the resonance held by the rest of the quartet.

This resonance is barely modified from its original form in Artemis, except when it extends to some of the measures added in Audéeis to accommodate the sung text.21

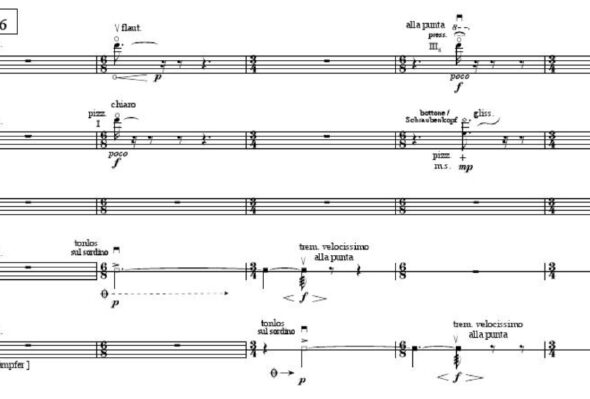

In sections where the cantaor does not intervene—neither singing nor with flamenco percussion—Audéeis retains the structures already present in Artemis. Consequently, the beginning and end of both pieces remain practically identical. Before the cantaor’s first intervention, two common structures in string quartet writing can be distinguished. Firstly, an almost soundless hint2268 of what will later become the rhythmic ‘framework’ for much of the piece: perhaps latent traces of what will later be the central bulería or the final siguiriya (rhythms contained in 3/4 and 6/8 measures).23 This structure is diaphanous and ‘incomplete’24 , likely generated—as we will see later—through subtractions. Secondly, a contrapuntal structure produced by successive overlapping ascending scale fragments, which unfold flowing through the initial framework structure before gradually dissolving (p. 5, b. 38). This ‘coexistence’ of structures suggests that both could actually be different ‘degrees’ of the same original structure, where the first is a ‘simplified’ layer of the second (after subtracting the scalar material).

The fact that this section is one of the string quartet reworkings of an orchestral passage from Chalan reinforces the idea of considering both structures in Audéeis (and Artemis) as more or less faithful reworkings of the original. According to this hypothesis, the opening corresponds to a focus solely on the parts of Chalan performed by brass (horn in F, trombones, and tuba), percussion (water gong), and piano, while the second structure (marked with Wellenartig, an indication that also appeared in the corresponding passage of Chalan) also incorporates the scale work of the string section. To verify these reworkings, see Chalan (p. 8, b. 19 and following) and the two fragments presented below, exemplifying the initial reworked structures of Audéeis.

Beyond the numerous adaptations from the original orchestral structure to the chamber setting of the string quartet, it is necessary to consider the changes made to measures and tempo indications. However, despite a certain distance, the similarities between both works are notable. These similarities are reinforced by the composer through the use of the same rhetorical indications and identical scalar material.25

The initial section—referred to by Sotelo as “breath” or “the formless”—is revisited at the end of the piece, once again presenting the diaphanous structure mentioned earlier, as if the application of further ‘subtractions’ revealed that ‘fragile’ layer that remains from the beginning. It is a cyclical closure that gives shape to the journey undertaken so far, presenting a common return point, revisited in an almost retrograde (but incomplete) manner.

Another structure appears between this common point and the cantaor’s final intervention: a contrapuntal framework in which ascending and descending fragments intertwine, constructed from fifths and fourths. 26

Notably, the interventions of the quartet’s instruments alternate—though some remain in the background as resonance—recalling the free hochetus of the percussive section, arranging melodic fragments (brief intervallic successions) in space, which within the quartet seem to constitute the spatialized melodic trait of a single meta-string instrument.

The sonority of the work also depends on the timbre employed by Sotelo, on the colors that tint the waters of his music. In general, Audéeis differs from Artemis through the inclusion of timbres characteristic of flamenco, which in Artemis were merely “imagined” or “virtual”: cante, cajón, and palmas. These timbres are drawn from flamenco tradition and incorporated into the new piece with almost no modifications. It is almost a transcription process,27 in which the result is redefined by the context— in this case, the string quartet—surrounding and permeating it until a new, unique music emerges, one inherently belonging to Sotelo.

This respect for flamenco tradition translates into the natural use of its elements; that is, the cantaor, cajón, and palmas integrate into the experimental string quartet context without signs of alienation. They do not assume a function different from their origins, nor do they employ extended techniques or ‘pretend’ to be something they are not. It is these roots that offer a compelling dialogue with the experimental framework of the string quartet, which in turn draws inspiration from flamenco, adapting to assimilate its essence.28

While the vocality of the cantaor and the percussion he employs are drawn from purely flamenco waters, the string quartet presents a less conventional timbral approach, particularly in the percussive section. Without losing sight of the classical string quartet tradition, Sotelo draws from more contemporary waters, incorporating more recent timbral techniques. He integrates new extended techniques for string instruments developed by German composer Helmut Lachenmann, particularly tonlos29 and a distinctive articulation method: striking with the metal part of the bow.30 Both indications appear in German, and if we examine the ‘silent’ bulería already used in Degli Eroici Furori, the first quartet employing similar techniques to those in Audéeis, we can observe Sotelo’s deep admiration for the German composer, even specifying: “Bulería, homage to Helmut Lachenmann.”31

The timbre of Indian music also finds its place in the waters of Audéeis, determining certain attack modes—such as pizz. ‘Hindu’ (p. 25, b. 179)—and significantly influencing the percussive section, where the flamenco cajón (and later las palmas) coexists with the string quartet, transformed into a “virtual percussion instrument.” Sotelo specifies in the legend that “the [string] section must play with great rhythmic precision and a rich palette of sonorities, like an Indian tabla.”32 The reference to the Indian instrument reaffirms the influence of the work undertaken in Chalan—completed one year before the composition of Audéeis—alongside the Indian tabla master Trilok Gurtu, serving as further evidence of how Sotelo’s experiences slowly ferment, maturing into his own musical production and enriching his sonic ocean.

However, the timbral indications for the string quartet also imply an intervallic or harmonic function—”not just timbral”—33, acting as a sort of bridge between musical parameters. This concept, closely linked to the music of Nono, was observed and later applied to his own compositions by Sotelo:

[…] the indications for the bow’s contact point—more widely known—but in Nono’s case serving a completely different function, together with dynamics. A function we might call intervallic or micro-intervallic rather than ‘timbral,’ or at least not purely timbral. In works such as Hay que caminar soñando, for two violins, one can hear—not only the different zones of the harmonic spectrum more strongly illuminated than the fundamental note itself, which in many cases disappears—but even small variations or micro-intervallic oscillations that do not depend so much on the position of the left hand, but rather on the speed, amount, pressure, and position of the bow; elements with which the composer is able to construct a true ‘Skala-mikro’ without the need to alter the diatonic-chromatic corpus […].34

In this way, the numerous indications for bow friction—sul ponticello, ordinario, tasto, flautando, etc.—that run throughout the pages of Audéeis, along with the precise dynamic markings that accompany them, do not merely define a specific timbre for the string quartet but also serve to enhance “different zones of the harmonic spectrum,” as well as to generate “micro-intervallic variations or oscillations” in a manner similar to what occurs in the works of the Venetian composer. In Sotelo’s case, however, these micro-intervallic variations or oscillations are added to the specific microtonality already present in the writing for both the string quartet and the cantaor.

Regarding the timbral work related to bowing, three significant techniques are also indicated, enriching the sonic palette of the quartet: legno battuto35, crine e legno36 (suono cristallo), and *arco ‘barroco’*37 (baroque).

Finally, as just mentioned, dynamics also play a fundamental role in shaping the sonority of the work. In Audéeis, they are meticulously indicated,38 often spanning—gradually—the entire range from ppp and even pppp tenuto (p. 55, bb. 507-512) to ff, and at certain points fff or ffff. These two cases of dynamic saturation—where fff (p. 49, b. 484)39 and ffff (p. 28, b. 228)40 appear explicitly at the individual level and implicitly reinforced at the global level—have a structural function, as they help delineate the poetic path of Audéeis.

Additionally, it is worth highlighting the tenuto of pppp, as Sotelo frequently employs this extremely subtle dynamic as a fleeting beginning or ending of a dynamic gradient, distinguishing it from dal/al niente, which he uses when he needs to completely blur the boundaries of silence. Sotelo’s use of silence and its thresholds brings us once again to the aesthetics of his master and to the verses of his esteemed poet:

In Valente’s hendecasyllable, we might find the solution to

one of the ‘enigmas’ of the quartet Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima […].

We refer to the fermatas […], which mysteriously fill the

pages of the work. Nono writes at the beginning of the score:The fermatas must always be perceived differently with free fantasy.

of dreamlike spaces – sudden suspensions – of ineffable thoughts –

of tranquil breaths [sic.] – and of silences to be “sung” “timeless” [sic.]«Se oye tan sólo una infinita escucha» [Only an infinite

listening is heard], could, indeed, be written above eachof the fermatas, which, like a space or void, allow the silences

or sounds on which this score rests to resonate ad infinitum.41

In addition to working on the thresholds of silence, Sotelo occasionally indicates the need for a gran pausa (G.P.) or places fermatas over what would otherwise be small silences or even breath commas, allowing space for the “infinite listening.” Regarding the measured pauses interspersed within the quartet’s work—sometimes including the cantaor—it is interesting to recall what Ordoñez Eslava observed about the Madrid composer’s use of them in Chalan, noting that “they must be understood as the natural pauses the cantaor takes for breathing.”42

Returning once again to sound, Sotelo’s use of layered dynamics in the heterophonic sections43 recalls, in a certain way, the ‘zones of intensity’ conceived by Edgard Varèse, which “would be differentiated by different timbres or colors and different volumes.”44 However, in Audéeis, although these ‘zones’ present slightly different timbres and dynamics (volumes), they primarily serve to generate a ‘three-dimensional whole’ rather than a ‘superimposition of different surfaces,’ as they belong to the same heterophony. Consequently, this use of layered dynamics seems to seek, through a sort of additive instrumental synthesis,45 to recreate a timbre—that of the cantaor’s voice—ultimately generating a new one that provides the work with a unique sonority.

Friday, September 22, 2017

“I have also based my work heavily on spectral techniques. That is, if I am in D (for example, tangos in D), I will use the spectrum of the tonic and the fifth, D and A. From this point, I will begin working with spectral filters […]. Furthermore, I use flamenco cadences in an almost literal way (literal/modern/advanced) […]. But always integrated within a spectral harmony.”46

[continue…]

- 1. FRANK HAASE, ‘On the Beginnings of Media Theory in Hesiod and Plato’, Pantelis Michelakis (ed.), Classics and Media Theory, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2020, pp. 115-146. “The divine had to enunciate itself—that is, be semiotized in the structure of human discourse—to become audible. The translation of audé as ‘inner power’ inherent to the divine voice is only a faint approximation of what is reserved during the bringing-to-earth of the divine and what makes it special. In reality, with the term audé, Hesiod prefers to comprehend the enunciation of the divine in the sense that the divine is endowed with human discourse (audéeis), or that human discourse is endowed with the divine.” [TdA] ↩︎

- 2. SOTELO, ‘Memoriæ’, op. cit. “imaginada voz flamenca”, “virtual instrumento de percusión” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 3. A possible translation of ‘entreverado,’ a term borrowed from flamenco guitarist José Manuel Cañizares, who uses it to refer to Sotelo’s music. See RUTH PRIETO, ‘Entrevista con Cañizares’, Mauricio Sotelo, Proyecto Mauricio Sotelo, El Compositor habla [online], 2017. https://www.elcompositorhabla.com/es/biblioteca-entrevistas/mauricio–sotelo_325.zhtm [last accessed: January 15, 2025]. ↩︎

- 4. On the implementation of the palimpsest in music, see the works of Andalusian composer José María Sánchez-Verdú, cf. JOSÉ MARÍA SÁNCHEZ-VERDÚ, ‘La tradición como fuente para la creación musical actual. Comentarios sobre el uso de algunas tradiciones en mi obra’, Catálogo de la Academia Española de Historia, Arquitectura y Bellas Artes de Roma, 1997 ↩︎

- 5. VALENTE, ‘Antología…’, op. cit. ↩︎

- 6. JOSÉ ÁNGEL VALENTE, Poesía completa, Andrés Sánchez Robayna (ed.), Barcelona, Galaxia Gutenberg, 2014. The previously consulted anthology does not contain the poem in question ↩︎

- 7. VALENTE, ‘Antología…’, op. cit. ↩︎

- 8. ORDÓÑEZ ESLAVA, ‘La creación musical de Mauricio…’, op. cit., p. 159. It should be noted that “it is essential to consider the value that cante flamenco holds within the poetic corpus of the author from Orense, as [José Ángel Valente] states: ‘One sings inward, into the body and the voice, towards the entraña [the depths] or—if we wish to use a term from Spanish mysticism—towards the entrañal [the visceral]. Such is the movement towards the depths or the jondo in singing […]. The cantaor, in cante, sings or sings himself towards interiority, pulling us into it. He sings towards the most intimate or profound part of himself, with a voice that plunges and withdraws into the deepest throats of the soul.’” [TdA], words taken from JOSÉ ÁNGEL VALENTE, La experiencia abisal, Barcelona, Galaxia Gutenberg, 2004, p. 37. ↩︎

- 9. Although in Sotelo’s words addressed to Artemis—which can be extrapolated to Audéeis—there is also a possible allusion in French to Baudelaire’s verses: “un rêve de pierre.” ↩︎

- 10. These syllables are called bol, cf. the section of this analysis focused on rhythm, pp. 36-41 ↩︎

- 11. GUILLERMO CASTRO BUENDÍA, ‘De playeras y seguidillas’, Sinfonía Virtual. Revista Gratuita de Música y Reflexión Musical, no. 22, January, 2012, p. 59. “This author [Manuel García Matos] interchangeably uses the different terms ‘siguirilla,’ ‘seguidilla,’ and ‘seguiriya’—in addition to the mentioned ‘siguiriya’—to refer to the same flamenco style.” [TdA]. In Audéeis, ‘Siguiriya’ appears in the collected texts in the legend at the beginning of the piece, while in the score, it is written as ‘Seguiriya’. ↩︎

- 12. SOTELO, ‘Audéeis’, op. cit., p. 9. ↩︎

- 13. Francisco José Arcángel Ramos. ↩︎

- 14. Especially in cases where the techniques used have been drawn from the aesthetics of German composer Helmut Lachenmann. On the influence of his music on Mauricio Sotelo’s string writing, cf. Ma CARMEN ANTEQUERA ANTEQUERA, Catalogación sistemática y análisis de las técnicas extendidas en el violín en los últimos treinta años del ámbito musical español, Universidad de la Rioja, Doctoral thesis, 2015. NB: In a passage common to both pieces, the term ‘lirico’ used in Audéeis (p. 23, b. 158) appeared in Artemis in German: ‘lyrisch’ (p. 19, b. 158). ↩︎

- 15. MAURICIO SOTELO, Si después de morir…, UE 32 548, Viena, Universal Edition, 1999-2000. ↩︎

- 16. SOTELO, ‘Memoriæ’, op. cit. «Podríamos hablar del intento de crear un instrumento musical nuevo, sobre la base de una antigua praxis musical: el Flamenco. […] Un cuarteto de cuerda que se convierte en imaginada voz flamenca, pero también en virtual instrumento de percusión» [TdA]. ↩︎

- 17. ‘Heterophony’: “This term is often used in ethnomusicological studies to describe a simultaneous variation, either accidental or deliberate, of what is identified as the same melody. According to Peter Cooke, ‘Heterophony,’ in *Grove Music Online” [TdA], cited in ORDÓNEZ ESLAVA, La creación musical de Mauricio…, op. cit., p. 195. ↩︎

- 18. The second violin approximately follows the double octave in relation to the cantaor’s voice, while the first violin follows the fifth or fourth above the second violin’s profile. See the section of this analysis focused on harmony, pp. 22-28, particularly the information related to spectralism. ↩︎

- 19. ‘Hochetus’ (or ‘Hoquetus’): “A polyphonic device […], characterized by the fragmentation of voices through pauses between syllables (and the deliberate use of syncopation between voices), thus creating a hiccup effect (Fr. *hoquet),” in Treccani [online], https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/hochetus/ [last accessed: January 15, 2025]. ↩︎

- 20. In the first intervention of the cantaor (p. 9, bb. 67-69), this ‘naked’ voice was already present. However, after these first three measures, the heterophonic work mentioned earlier begins. ↩︎

- 21. See the section of this analysis focused on formal construction, pp. 42-46. ↩︎

- 22. This reference consists of a sort of pointillism—achieved through very brief articulations in the quartet— that is ‘waved’ by the “marine rustle” to which the Madrid composer refers. See SOTELO, Memoriæ, op. cit. ↩︎

- 23. See the section of this analysis focused on rhythm, pp. 36-41. ↩︎

- 24. Or, in Sotelo’s words, “lo informe.” See SOTELO, Memoriæ, op. cit. ↩︎

- 25. This will be addressed later. See the sections of this analysis focused on harmony and melody, pp. 22-28 and pp. 29-35, respectively. ↩︎

- 26. See the section of this analysis focused on melody, pp. 29-35. ↩︎

- 27. Regarding the transcription of Enrique Morente’s cante in Audéeis, see the section of this analysis focused on melody, pp. 29-35. ↩︎

- 28. Such as microtonality and the articulation of highly melismatic ‘vocal spaces.’ ↩︎

- 29. SOTELO, Audéeis, op. cit. In the legend, it is specified: “play without sound by passing the bow directly on the wooden mute while the left hand slightly dampens the strings” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 30. Ivi. In the legend, it is specified: “place the metal adjuster of the bow on the string. Immediately after plucking (pizz.) the string with the left hand, move the adjuster in a looping motion along the string. A high-pitched, metallic glissando is heard” [TdA]. This technique is taken from the music of Helmut Lachenmann. See ANTEQUERA ANTEQUERA, Catalogación sistemática…, op. cit., pp. 115-116. “Lachenmann also uses this technique in his work Toccatina or in Grido, String Quartet No. 3” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 31. SOTELO, Degli Eroici Furori, op. cit., p. 9. ↩︎

- 32. SOTELO, Audéeis, op. cit. ↩︎

- 33. SOTELO, Luigi Nono o el…, op. cit. ↩︎

- 34. Ivi, p. 25. “[…] las indicaciones del punto de fricción del arco –por otra parte más conocidas– pero en Nono con una función, junto a la dinámica, completamente distinta. Una función que podríamos llamar intervalica o microintervalica y no ‘tímbrica’, o no solamente tímbrica. En obras, por ejemplo, como Hay que caminar soñando, para dos violines, pueden oírse –además de distintas zonas del espectro armónico más fuertemente iluminadas que la propia nota fundamental, que en muchos casos desaparece– incluso pequeñas variaciones u oscilaciones microintervalicas, que ya no dependen tanto de la posición de la mano izquierda, como de la velocidad, cantidad, presión y posición del arco; elementos con los que el compositor llega a construir una verdadera ‘Skala-mikro’, sin necesidad de alterar el corpus diatónico-cromático […]” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 35. SOTELO, Audéeis, op. cit. In the legend, it is specified: “strike the wood of the bow on the indicated pitches (contact point) while the left hand slightly dampens the strings” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 36. Ivi. In the legend, it is specified: “play with both the hair and the wood of the bow” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 37. N.B.: No bow change is expected, but rather the use of the modern bow in a way that recalls the sound of the Baroque bow. ↩︎

- 38. Except for the vocal intervention in the bulería, where no dynamic indication is provided, thus granting the cantaor a certain interpretative freedom. Regarding the ‘free’ use of flamenco as ‘independent parts’ in Sotelo’s music, see the section of this analysis focused on melody, pp. 29-35. ↩︎

- 39. The fff articulates the transition from the “rêve en pierre” (the final percussive interventions of the cello material) to the “vibrant voice” (the beginning of the Seguiriya). ↩︎

- 40. The ffff prepares the transition from the Quejío (the saturation of the string quartet that ‘evokes’ the shared memory: “¡recuerda!”) to the “rêve en pierre” (the silent bulería). ↩︎

- 41. SOTELO, Luigi Nono o el…, op. cit., p. 27. “En el endecasílabo de Valente podríamos encontrar la solución a uno de los ‘enigmas’ del cuarteto Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima […]. Nos referimos a los ‘calderones’ o ‘corone’, que misteriosamente pueblan las páginas de la obra. Escribe Nono al inicio de la partitura: Le corone sempre da sentire diverse con libera fantasia. – di spazi sognanti – di stasi improvvise – di pensieri indicibili – di respiri tranquilli – e di silenzi da ‘cantare’ ‘intemporal’

‘Se oye tan sólo una infinita escucha,’ podría, efectivamente, escribirse sobre cada una de las ‘corone’ que, como un espacio o vacío, dejan resonar ad infinitum los silencios o sonidos sobre los que en esta partitura reposan” [TdA]. ↩︎ - 42. ORDÓNEZ ESLAVA, La creación musical de Mauricio…, op. cit., p. 173. “deben entenderse como las pausas naturales que el cantaor dedica a la respiración” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 43. N.B.: In *Audéeis (p. 9, b. 63), the following dynamic stratification can be observed: ppp (shadow sound), pp intimate, and pp intimate ‘in relief.’ ↩︎

- 44. EDGARD VARÈSE & CHOU WEN-CHUNG. “The Liberation of Sound.” Perspectives of New Music, vol. 5, no. 1, 1966, pp. 11–19, p. 11. “would be differentiated by various timbres or colors and different loudnesses” [TdA]. ↩︎

- 45. ‘Additive synthesis’: “It is the process of synthesizing new complex sounds by adding simple sounds (usually sine waves) combined together. Since pure sine waves have energy only at a single frequency, they are the fundamental building blocks of additive synthesis, but naturally, any type of signal can be summed. […]” [TdA], in *Max MSP’s Synthesis Tutorial 1: Additive Synthesis in Max MSP’s Synthesis Tutorial 1: Additive Synthesis [online].

https://docs.cycling74.com/legacy/max7/tutorials/06_synthesischapter01 [last accesse: 15 gennaio

2025].. ↩︎ - 46. CARLOSROJO DÍAZ, ‘Entrevista a Mauricio Sotelo II’, Cultura Resuena [online], 2017. «Me he apoyado mucho también en el trabajo espectral. Es decir, si estoy en re (por ejemplo, unos tangos en re) voy a utilizar el espectro de la tónica y el quinto, el re y el la. A partir de ahí empezaré a trabajar con filtros espectrales […]. Además, utilizo de una manera cuasi literal (literal/moderna/avanzada) las cadencias flamencas. […] Pero siempre integrado dentro de una armonía espectral» [TdA]. ↩︎