Recognized as one of the most significant composers of his generation, Oscar Bianchi has composed for numerous musical ensembles since the early 2000s, creating innovative works that have shaped a refined style and a continuously evolving language. His career is enriched by significant experiences, many of which feature the guitar as a critical element. In this dialogue, we explore the pieces that have defined his work for the six strings.

Oscar, thank you so much for accepting our invitation.

You have studied in renowned centers for new music, such as Milan, Paris, and New York, where you also participated in a doctoral program with Tristan Murail. How did these experiences shape your work, and what do you think they have left you with that is most significant?

Every one of these experiences was a crucial chapter in my intellectual and personal growth. I recognize in each of them the foundations of the artistic thinking that has accompanied me until now. Milan was my hometown, and with it, at the G. Verdi Conservatory, the first expressions of my ideals took shape; here, my passion for a distinct style of sound and a sense of “mission” regarding music-making ignited. Despite its many gaps, the famed conservatory in Italy allowed me, thanks to prominent figures like Adriano Guarnieri, to engage in an introspective work that proved crucial, especially concerning ideals and a sense of utopia in music. Then came Paris, the great revelation in my artistic and formative journey, where culture (unfortunately, at times almost in opposition to my country of birth – that was the feeling) is embraced, respected, celebrated, and supported. New York was the stage of significant cultural and personal freedom and a genuinely new world for me. The geographical distance from Europe (whether real or perceived) and the absence of the need to conform to any local aesthetics (whether French, Italian, or German – in the early 2000s, the notion of school was still powerful) gave me the strength and allowed me to defend even more fiercely a possible “own style,” own music proposals, something that, as for most young composer, I felt particularly fragile about.

In a composer’s career, the path toward writing for guitar is often gradual: one starts with classical guitar and gradually moves toward electric sounds. Your story, however, seems to follow the opposite path. Lines and Pictures of an Explosion, written in 2000, include electric guitar and bass. Where does this choice come from? How did you approach the six strings?

At that time, fresh from experiences and explorations within progressive rock and fusion bands, the immediacy and exuberance of the sounds possible with electric guitar and bass were both part of my musical fiber during that period and of the vision I had for a sound that was at times brash, dominant, and anti-bourgeois (which I did not want to disregard). I wanted to combine the freshness I had felt in that extra-classical/non-classical contemporary world (without espousing its stylistic references or clichés) with a musical language that could embrace mystery and absoluteness.

After Mezzogiorno, written in 2005, you composed Zaffiro for guitar, viola, bass flute, and baritone saxophone. The classical guitar appears nearly five years after your first approach to the six strings. What challenges did you encounter in composing for this instrument? And what differences did you notice in the transition from electric to classical guitar?

The challenge was finding an equivalent to the sharp and complex essence typical of the electric guitar, simulating its immediacy and that sense of urgency that has always fascinated and intrigued me (also in string instruments, in general). This translated into a rather tense, reckless use of the acoustic guitar, still carrying some idiomatic dimensions (compared to Thick Skin, for example). At the same time, the classical guitar, even in this context, allowed for a sense of contemplation within the acoustic sound (especially around its extraordinary natural resonances), the value and interest of which then led me towards the spiritual work of the cantata Matra.

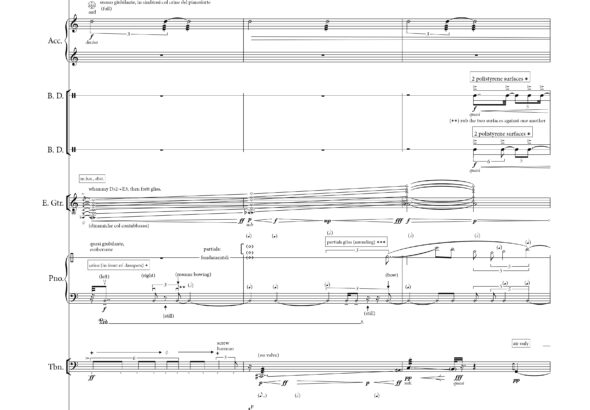

In 2007, you wrote Matra for the Ictus Ensemble and Neue Vocalsolisten-Stuttgart, including the electric guitar. Was it difficult to incorporate this instrument into such a large ensemble? What challenges did you face?In this case, it was not difficult because the electric guitar, in my imagination, was already an integral part of a “sonic arsenal” that was being defined. Its boldness and contemplative capacity were instrumental in bringing to life the “otherness” that the cantata Matra sought.

After Stone Rhapsody in 2008, for guitar, two pianos, and two percussionists, your guitar production stopped for a few years. During this period, you focused on large compositions for the ensemble (such as the Vishudda Concerto, for 19 players, written in 2009) and orchestra (like Inventio or Exordium, composed between 2015 and 2016). What led you to take a break?

I found it essential to engage with musical forms and sonic contexts different from those I had meticulously built. This was partly out of a sense of challenge, intellectual ambition, and especially an attempt not to discriminate against sonic worlds where I could find other responses, other variations of my language.

Significant experiences mark your return to solo guitar music. In 2014, Nico Couck received the Kranichsteiner Stipendienpreis, and in 2016, at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse, he performed Ballerina for electric guitar. This collaboration led to the creation of Étoile in 2020, which was performed in Sochi in February of that same year. How did all of this come about?

Thanks to Nico’s proposals, I was given the opportunity to reconnect with the instrument from an entirely new perspective. I wanted to aim for a complete and personal exploration of this instrument, placing it at the center of a new musical, compositional, and symbolic virtuosity. If Ballerina was an expansive, free creative space whose output was at times conceptual, Étoile was, in every way, a comprehensive exploration of the semantic possibilities that this instrument revealed to me during a period filled with the desire to expand its expressiveness and purity without exclusions. For this reason, within it, you find, for instance, connections between a cadenza—a tribute to Van Halen (the historical icon who passed away ten months after the premiere of Étoile)—and the abstraction of pedal sound beatings, whose partials, produced by distortions, then became harmonic material embraced and developed by the orchestra.

In 2016, you wrote Reinforced Sympathy for two ouds, which were very particular and challenging instruments to handle at the time of writing. It was also a collaboration with the European and Egyptian Contemporary Music Societies. How was this experience?

As they say in America, a “reality check,” or rather, a “cold shower,” essentially because of my ignorance. After working for weeks with two magnificent performers in Cairo, with the support of Elena Schwarz (and integrating a classical poem by Al-Mutanabbi in Arabic to help with the rhythmic patterns, which would otherwise have been too abstract for the musicians), I realized that, as with many musicians from traditional backgrounds, musical writing does not hold the same value as oral transmission and improvisation. As a result, every following morning, the musicians only remembered something out of the solid and impressive work they had done the days before. Many revelations from this rich experience informed later on my orchestral piece Inventio for the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) and, in a very different form, Thick Skin.

In 2018, you explored an unusual ensemble: you composed Circled Existence for Marc Sinan and the Neue Vocalsolisten-Stuttgart. This composition features a 12-string guitar with a smaller scale, other than an electric guitar. What was the reason behind this choice?

A semantic connection between an instrument with a concertante role—fundamental but not soloistic—and the heterogeneous, organic world of the six vocal chamber musicians. With their euphoric “sympathy,” the twelve strings generate complexity and richness of beatings within the concertante instrument while, by being to some extent exceptional, “compensate and challenge” the six voices it accompanied.

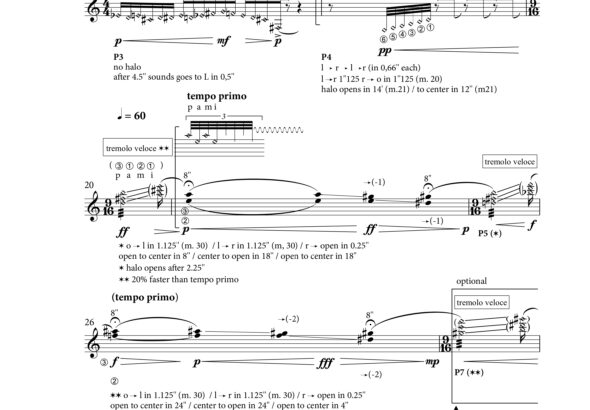

Thick Skin (Stratum Lucidum), from 2022, is your latest work for solo classical guitar, in which Francesco Palmieri also engages with electronics. A piece both refined and aggressive, it explores the instrument in all its dynamic possibilities, pushing it to the limits of its capabilities. What were the most stimulating challenges in creating this work?

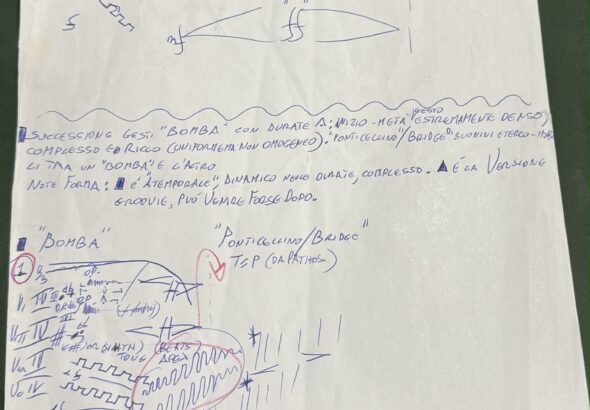

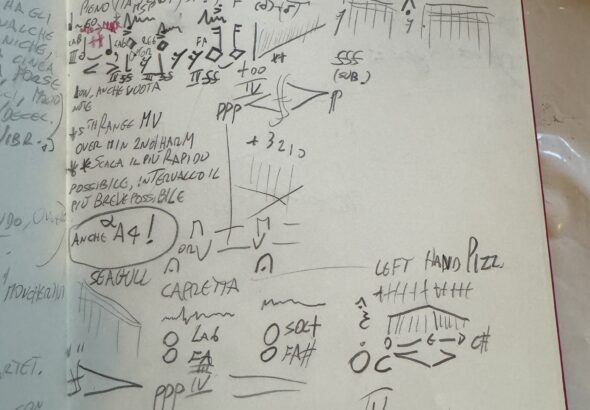

I would describe this piece as pivotal since, for the first time, alongside insights already present in Ballerina (2016), I pursued what I’d call an “expanded temporality,” a sense of time that was plastic, unpredictable, and cathartic. This is achieved through eliciting sounds and instrumental behavior that are partially unpredictable and organic, sometimes almost anti-idiomatic in perhaps the most traditional sense. The dissolution and contraction of times mark perhaps a battle (or a wish) to dismantle predictability, opening a path toward contemplation through active listening.

Plenty for Two, written for MusikFabrik and featuring Yaron Deutsch on guitar, represents the most recent work in your output for this instrument. Throughout your career, you’ve collaborated with prominent soloists such as Mats Scheidegger, Tom Pauwels, Nico Couck, Marc Sinan, Francesco Palmieri, and Yaron Deutsch—figures who have shaped and continue to shape contemporary guitar. How much does the performer’s figure influence a piece’s composition?

Enormously. The pieces I wrote in collaboration with each of these performers were deeply influenced by their personal history with the instrument. It was through them that embryonic ideas were able to develop. For example, the opening tremolo in Thick Skin was a clear image and a solid leading idea. However, it couldn’t have been translated to reality without Francesco’s artistic and technical perspectives. The performer’s influence and interaction with the composer is often an osmotic process between what the composer feels and what the great interpreters propose or suggest— sound worlds, whether intuitions or vivid images, often emerge only through a collective effort.

What elements should always be present in the role of a teacher?

The ability to make the ego (of the teacher) disappear altogether, to become an antenna for possible solutions through malleability and intuition. To share the essence of inspiration.

You have been leading the Young Composers Academy in Ticino for several years. Where did the idea come from?

To create a musical future without boundaries and from the desire for connection and growth. The opportunity to share my journey and experiences with young composers while engaging in a dialogue of ideas from geographically and intellectually diverse backgrounds.

Do you follow a particular working method during lessons?

With the ego absent, I transform, adapt, and adjust depending on whom I have in front of me. No two people are the same, and no interlocutor – consciously or unconsciously – deserves the same reactions and implications.