With over 150 compositions spanning every possible ensemble and exploring a wide range of genres, Sarah Nemtsov’s career is at its peak. Her musical language is constantly shaped by a remarkable variety of influences, which define the uniqueness of her music. In this conversation, we will delve into her works for guitar, focusing on her most significant compositions from the past and her future projects.

Sarah, thank you for accepting our invitation.

Your passion for composition developed alongside your studies as a performer, during which you pursued a career as a recorder and oboe player. How has being a performer influenced your creative and writing process?

Thank you! Being a performer has been incredibly important. Although I sometimes feel as though I started composing before truly playing an instrument (almost as if the seed for it was already there), the experience of making music has always formed the foundation of my writing. My first recorder teacher, Ilse Reil, was an extraordinary musician. She taught me fundamental lessons and I still draw upon them when I compose. She always delved deeply into the music; no note should ever be empty, and each note had to carry within it the necessity to lead to the next. We would practice the tension between two notes endlessly, but always with a sense of joy. I remember how we would sit next to each other, practicing together and laughing.

You began writing for classical and electric guitar between 2006 and 2007, as demonstrated in your ensemble pieces Communication – Lost – Found and Interludien. How did you become interested in this instrument, and what challenges did you encounter?

Initially, it was simply because of the commission. I was a student, and it was one of my first official commissions for a Berlin youth ensemble for contemporary music (led by Gerhard Scherer). I had always liked the guitar, but I don’t think I would have written for it if it hadn’t been part of the ensemble. And I made a lot of mistakes—writing in bass clef, including impossible chords, and so on. Today, we can just Google it, but things were different back then, at least for me. I still think the guitar is one of the most difficult instruments to write for, perhaps alongside the harp. With other instruments, things tend to work more or less, better or worse, and you can sometimes “cheat” a little. But the guitar is merciless.

Over the years, you have written numerous works featuring the guitar in various unique formations. I am thinking of Orbits (2018) for four electric guitars with scordatura and electric bass, Briefe.Puppen (2014) for electric guitar and percussion, and EMP (2023) for electric guitar and amplified violin. What led you to compose for such distinctive groups? I imagine your approach must have been entirely different compared to writing for an ensemble.

On one hand, I think I was driven by the specific challenges I mentioned earlier and by my own struggles—like wanting to climb a mountain and succeeding. It’s a bit of an obsession, and once you start, you can’t get enough. On the other hand, the guitar—especially the electric guitar with all its effects and possibilities—is such a rich and vast landscape. It’s completely fascinating, and I feel like I’ve only just explored a small corner of it.

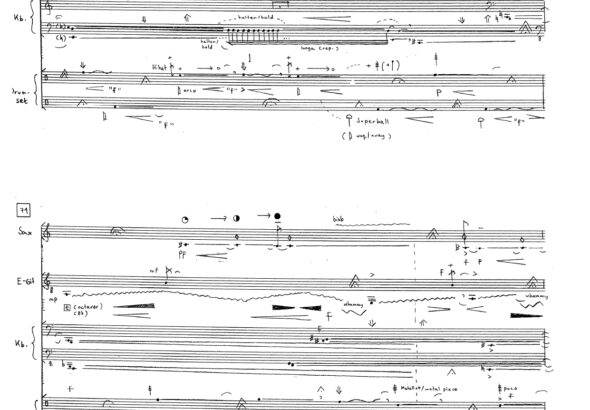

What I also love about this instrument is its unpredictability. So, even when writing very detailed music for the electric guitar, there is always space for the musician to bring their individual voice and approach. This feels like a gift: a form of communication that often leads to wonderful surprises.

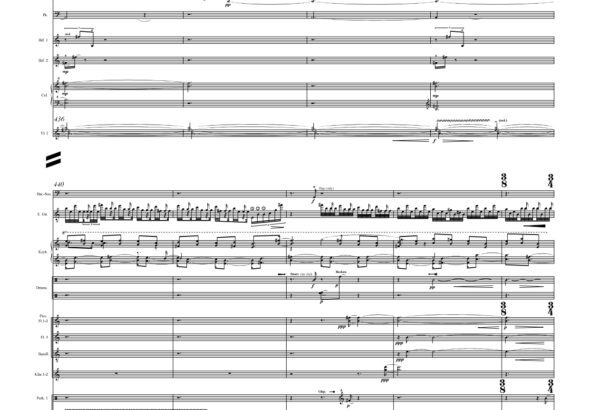

Of course, every setting is different, and the guitar plays a unique role in each. For instance, in MOOS, the guitar is conceptually an outsider, as part of several groups of musicians within the ensemble. But musically, its role depends entirely on the moment. It’s always different with every piece. The guitar can become the foundation for everything, the glue holding the ensemble together, a unique light shining on the others, or even just a satellite orbiting the whole.

In some compositions, the electric guitar serves as a central element from which everything evolves. In EMP, for electric guitar and amplified violin—written for Yaron Deutsch and Irvine Arditti—the electric guitar becomes a violin, and the violin becomes a guitar.

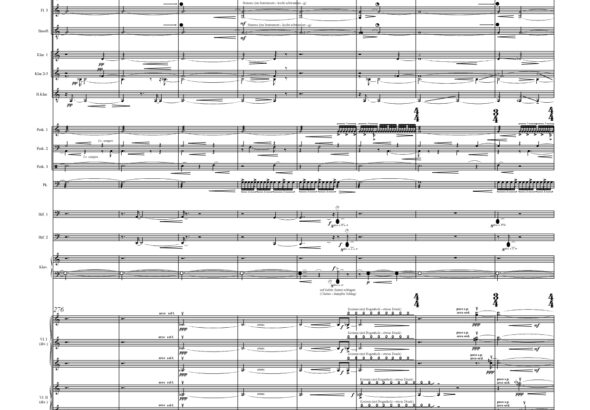

Your style often seeks sounds that repeat and contrast, creating loops and chaotic structures. In this context, the electric guitar (or acoustic guitar and electric bass, instruments you frequently use) fits perfectly, thanks to effects such as distortion, freeze, octaver, e-bow, chorus, and delay. With so many effects available, it can sometimes feel disorienting. How did you conduct your research to become familiar with such a versatile instrument?

I find effects fascinating because each one is a world unto itself, and combining them is never just a simple sum: it opens up new potentials. I also enjoy the unpredictability, especially with analog effect devices. I have a small collection of pedals and other machines, but working directly with musicians is crucial. That hands-on collaboration is where my experience grows and where the roots of my imagination take hold.

For me, it’s always essential to focus and make decisions early on—once I have a clearer idea of what I want the piece to achieve—about what is truly necessary. From there, I prefer to explore deeply within those boundaries rather than constantly adding new elements.

As for loops: yes, there are loops in my music at times, but I wouldn’t define my music as loop-based. Quite the opposite, especially in recent years. I’ve been striving to build longer phrases or paths that evolve in unexpected ways. The landscape shifts, the line becomes disrupted, the direction gets corrupted, and sometimes it even becomes stuck in a loop. But a loop can also be something else entirely: a manifestation of joy, dance, a trance-like state, or a threshold for change.

Over the years, you have built a strong relationship with interpreters. This is the case with Seth Josel, the dedicatee and performer of several works, including the aforementioned Briefe.Puppen (2014), as well as verflucht (2019), an operetta featuring acoustic guitar, and the opera Sacrifice (2017). Another example is Yaron Deutsch, with whom you collaborated on the tetralogy TZIMTZUM (2020–2023), written for Ensemble Nikel and involving the participation of an orchestra. How important is the role of the performer in your music?

The role of the performer is incredibly important. I learn so much from them, and this is true for many instruments and performers. It’s not only their knowledge, virtuosity, and creativity as musicians that inspire me and leave me in awe, but also their personality—both in music and in life. Their individuality inspires my compositions and creates a deeper connection.

The pieces I write are also theirs in a way. This doesn’t mean the works cannot be performed by others later, but it does mean I could never have written these compositions without the specific performers and collaborators I’ve worked with. I’m lucky to often call them friends, and I am deeply grateful for these relationships. Trust leads to greater courage.

You are currently preparing a piece for Yaron Deutsch, DA’AT, for the ECLAT Festival.

In DA’AT, I will explore the concept of inner polyphony more deeply, working with different layers of sound and blending noise with pitch. I will delve into microtonality once again, seeking friction between harmonics and the beauty of instability or fragility in harmony. I am also trying to explore a quieter space in this piece, but I am not yet certain how it will fully materialize.

You often speak of literature and painting as your main sources of inspiration, influenced by your mother, the painter Elisabeth Naomi Reuter. How does your music change when you reference an art form other than music?

Being surrounded by my mother’s art during my childhood, and later in life, had a significant impact on my music. However, I only truly understood this influence after her passing. In general, literature and painting are important to me, as well as other art forms, experiences, and topics. It all comes naturally. Still, music and sound remain the core. A reference should never be something superficial or simply added on top; it must be deeply interwoven. I enjoy trying to translate non-musical elements into my music to see what happens and allow my musical language to grow. Through other art forms, I may find sounds, forms, textures, or concepts that I would never have considered otherwise.

This is a vast topic. I am also writing operas (which, by the way, include electric guitars in my compositions!).

For about ten years, you have been incorporating electronic music into many of your works, using it as a bridge to connect with instruments; you often include audiovisual material. How do you envision the future of Sarah Nemtsov’s music?

I have no idea. Luckily. At the moment, I am focusing more on pitch and harmony again, but with a sense of morphing. For a long time, I thought in layers, but now it feels different, though it’s hard to describe: almost as if the polyphony is happening more vertically, more deeply, with everything having a different amplitude than before. Nevertheless, the relationship between acoustic and electronic sounds still fascinates me, and there’s so much left to explore. While I may be exploring the more vulnerable aspects of sound, I am also trying to find electronic-like sounds within acoustic instruments or ensembles. I hope to write much more for orchestra in the coming years.

Thank you for your interest in my music.