The profound depth of his works and his refined exploration of sound make Marco Momi one of the standout composers of his generation. Born in Perugia in 1978, Momi studied piano, conducting, and composition in Perugia, Strasbourg, The Hague, Rome, Darmstadt, and Paris. He has won numerous international competitions, such as the Gaudeamus Music Prize and the Seoul International Competition, and has been a composer in residence at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin and the American Academy in Rome. His name regularly appears in the programs of major festivals like Musica Strasbourg, ManiFeste Paris, Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik, Milano Musica, and the Venice Biennale, with performances by Ensemble Intercontemporain, Nikel, Klangforum Wien, and Neue Vocalsolisten Stuttgart, among others. In this interview for Obiettivo Contemporaneo, we delve into some of the central themes of his music making, from the concept of scenarization to the role of writing and interpretation, with particular attention to his work for guitar and his relationship with guitarism.

One aspect that characterizes much of your work is the combination of acoustic instruments with electronics—typically of synthesis and in deferred time. How do you establish a narrative between these two perceptual dimensions? What role does electronics play in the dialogue with the instrument, and what relationship do you seek between the acoustic source and the speaker?

The question of narrative involves multiple layers. One of these is linked to the actors on stage. In recent years, I’ve worked a lot on a concept that could be defined as scenarization—composition of scenes, actorship, and the definition of actantial values. It’s a journey toward awareness of the narrative potential that has developed alongside my compositional need to work with elements such as the linguistic connotations of acoustic or electronic instruments, and their potential for organological redefinition (we can simply think of the role of actuators in today’s electronics or of instrumental preparations). The shift in sound emission and projection techniques that result from it calls for narrative choices tout court. However, I would separate this topic from the issue of electronics, which in my case needs to be understood as functionally as we might understand a violin—discussing it separately tends to orient reflection in terms of exclusivity compared to the acoustic component.

Regarding the relationship between the sources, from my perspective, and as I’ve developed over the last ten years, it is indeed an equal one. In many cases, we could start from the opposite reflection, asking what the instrumental role is within the electronics, rather than the other way around. I remember already in 2010, I focused a lot on this idea in Iconica IV, where in one movement, what I aimed to do was reverse the roles, so that the acoustic part would equalize the electronics.

I don’t create pure electronic music, and I will never make acousmatic music. I once made an installation for the Akademie der Künste in Berlin but later removed it from my catalog. This is to say, I don’t work with the materials of electronic research, simply because they don’t interest me. What I care about is the space where electronics come into friction or contact with acoustic identity values. So, from a purely frequential perspective, I’m interested in the shared space of sound radiation. This involves a whole series of situations that, over the years, have taken me far from the concept of synthesis—wonderfully developed by many of my colleagues—which is very selective and focused, grounded in the development of mathematical models, programming, coding, optimization, and continuous interaction with machines. What I am drawn to is a combination of synthesis and “dirt,” because it’s in this liminal space that, very often, mixed music emerges, at least in my case.

I say “syntheses”—many syntheses—because what I do in terms of electronics is an extreme multiplication of sources and the nature of the sounds themselves. I almost never work with just one or two sounds to compose a musical moment. Instead, I work with anywhere from 60 to 250 in the instant. As a result, my compositions revolve around the concept of layering acoustic multiplicities. It’s important to understand this to avoid misinterpreting my electronics as just electronics per se—in my tapes there is a lot of orchestration and composition of interaction with the performers.

How does the relationship between instrument and speaker change, if at all, when using an electric instrument instead of an acoustic one as in the case of Quattro Nudi for electric guitar and electronics? Can you tell us about the genesis of this piece?

It certainly changes. I must say, in the case of Quattro Nudi, I didn’t do any particular job on the distribution of sound sources. The piece was commissioned by Christelle Séry and some French research centers (Why Note, Césaré, GMEA, La Muse en Circuit). Generally, if I accept a project, I like to write for the performers, to build a relationship with what they have, how they work, what is their electric guitar, and so on. That’s what happened here; so, in terms of the setup, there’s nothing groundbreaking.

What is notable and clearly defined is the proximity of the two left-right sources in relation to the central positioning of the cabinet. This is because, in Quattro Nudi but also in Sans Dire and other works for solo instrument and electronics, what I enjoy exploring is the moment of augmentation or phase shift of the spatial portion from which the sound is radiated.

The arrangement of the sources, in terms of distance, borders on the classic 2+1 setup with the amplified instrument, with a proximity gradient that makes the left-right (or better, mid-side) sound field more or less defined and sculpted. If it were too wide, it would create a multiplied perception of the instrumental sound source, leading to a disorienting listening experience that I don’t like. In this sense, we’re talking about electronics as part of a sonic event that includes the live-performed acoustic part as well. But we’re also talking about a stereo listening logic, akin to that of a record. There’s a deconstruction of the listening mix, with different parts assigned to left-right and mid. These proximity gradients can be defined and measured empirically—it’s a very complex issue, requiring years of experience, and even now, I continue to explore and discover things. That small space where the mid then expands into the side, frays, and there’s a sort of onset of denaturation, a contamination of the acoustic part, is something I particularly enjoy. It’s a space that also needs to be shaped in the moment of the concert.

There are other cases of clear research on sound radiation. I wrote a piece for viola and electronics—which I’ve never heard live yet—where the speakers are not PA speakers, but nearfield monitors purposely placed out of phase, and the viola is positioned about a meter and a half behind the out-of-phase line. In the project Unrisen for the SmartPianoQuintet, instead of speakers, there are ten transducers placed on the instruments. Or in Almost Close, where there’s only one mono source coming from inside the piano, which is then reamplified using the piano’s sustain pedal—the piano itself becomes part of the speaker, organologically speaking.

I had never critically considered the traditional strategies of sound processing, amplification, and diffusion of the electric guitar until one of our conversations at the end of 2021. It was thanks to that stimulus from you that I began to investigate the question of spherical amplification, which is now central to my artistic research. What do you find, or found, unsatisfactory in that traditionally guitaristic approach to the instrument in relation to your sound culture?

What has always been difficult for me with the electric guitar is that the sound emission—an integral part of the instrument—was embedded, untouchable, closed off. It doesn’t allow for editability.

There are some ingrained habits among electric guitar performers that, in my opinion, tend to adopt what I call a “preset logic,” meaning the instrument’s color is determined by a specific amplifier, cabinet, etc. Then there’s another color created by another cabinet, another by a different brand, and so on.

On one hand, this approach carries a clear allure, along with cultural and linguistic references. Think of Vampyr!; in terms of composition, that work linguistically affirms a connection with, for example, Van Halen, so the piece brings with it a very strong linguistic value. I don’t like working exclusively with a dynamic of “new virginity,” where the linguistic aspect is completely erased. It’s absolutely present, weighed, and measured even in what I write. However, with the electric guitar, this became overwhelming and, above all, very difficult to control because we’re talking about instruments where, as a composer, you simply don’t have access.

This was quite disappointing for me. Part of what contemporary music does, like contemporary art, is redefining our relationship with matter. Every day we rediscover matter, every day we are challenged by it, and therefore, every day this rediscovery of matter imposes new systems on us to touch it, to relate to it.

What intrigued me was that this daily habit of investigating the redefinition of sound was completely absent in the practice of electric guitar playing—which I’ve come to know, adore, and enjoy. But it also caused me problems when writing. I tried to work through this in Almost Nowhere, in Ludica II, and also in Quattro Nudi, where there are still references to guitaristic gestures that are linguistically marked. However, I’ve not entirely succeeded in breaking free of it in terms of sound.

Your pieces are extremely demanding—not necessarily from a technical-instrumental perspective, but more so for the physicality, the gesturality, and the attitude required of the performer. Vital to the full realization of your music, much more than in other, is the performer’s ability to go beyond the written score, to be present, embodying and living each musical event as necessary. With this in mind, I’d like to ask you what role the performer occupies in your music, and what is your relationship with virtuosity (even if it’s of an anti-heroic kind)?

The performer plays a central role. What I aim to write are texts that open up a dynamic of valorization. The interpretative act, as I’ve come to know it through classical music—and still do today—is an act that, when faced with a text, at least in the case of great music, consistently and perennially forces us to make choices about how to bring out the value of the text and its co-texts: what’s in front, what’s on the side, what’s in the background, and so on. We were talking about scenarization earlier, so let’s use this metaphor of the stage: imagine characters; characters under a certain light; what kind of light with what kind of expression; what expression with what tone of voice; the character standing nearby; how close they stand and what their posture is like, and so on.

All of this takes effort, but it activates a hopefully ambitious textual value that I hope endures. It’s about writing how to read, often for illiterate people. Clearly, what I write is not meant to exist only in my present time. What I hope for my texts is that they will survive, and I try to defend them—then we’ll see.

Ultimately, what I aim to do is what happens to me—and has happened to me—with Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann—no more, no less. There’s a connection to the texts that pushes me to dive into them, to recalibrate their values. That’s why it’s challenging for musicians, because it’s clearly classical music, and classical music rarely allows you to take an unfamiliar composer, prepare a piece in a week, and go straight to concert. If that’s sometimes possible, it’s because there’s an established praxis, but in contemporary music, this praxis doesn’t always exist—or at least not entirely.

I write music that is interpreted, without question. Precisely for this reason, my pencil rejects anything that would make it an instructional piece or performance music in the sense of giving the performer an authorial role over the text. Instead, I often find myself talking about touch, fingerprint, the intention that precedes sound-making. These are things that interest me far more than giving any performer creative space to define time, notes, and gestures.

During a dinner, after I commented on one of your personality traits, you replied, “Well, you should know, you’ve played my music,” almost as if your person, your life, were inseparable from your music, or at least as if it were a reflection of it. Quoting one of your program notes, you wrote, “I cannot write impermeable music.” Is there a dimension of necessity in your composing?

The dimension of necessity exists not only in my composing, but I believe in the composing of many—there’s a wealth of wonderful literature on this topic, and I feel part of it. Regarding my presence in my own texts, there are a few things to say. I’ll start with the notion of impermeability. For me, not being impermeable means maintaining a dynamic relationship with my contemporaneity and the hours I live in. I’m not interested in static works. This forces me into a posture of imbalance with what I’ve just written. I’m not a serial composer, like Sciarrino, Ferneyhough, or Saariaho. I’m a prototypical composer. My nature generally compels me to place myself in a state of unfamiliarity with what I do. For me, it’s crucial to think of writing not as a manifestation of myself but quite the opposite. Writing allows me to step outside myself, to simulate being someone else. It’s a multiplication. And that was something I had to learn, because when I was younger—perhaps due to the career pressures we all faced—there was this myth of recognition and identity. And that’s something that doesn’t interest me at all—I eventually realized it just doesn’t.

When people started asking me for pieces because they wanted something similar to my previous works, or they began stylistically defining my music, it bothered me immensely. So, many times, I’ve forced myself to undergo strict diets and take radical shifts in direction. But in reality, this is an exercise in alterity. Multiplying the viewpoints of what can be written is absolutely central to me. I’ve often found myself feeling unwell, writing things that were completely distant from my sensibilities, from my musical—or even more so, my human—nature. But they had to be done. I’m quite convinced that there’s a need to be something other than ourselves, to become other. Even the current social reflections on the concept of identity and the defense of identity are completely opposed to my desires. Forcing oneself to do things that are outside of us has to do with a duty of research that we impose on ourselves to continuously redefine ourselves. Otherwise, we just keep talking to ourselves or in an autoreferential loop with our own circles.

In discussing Ludica II during a 2013 interview, you highlighted the challenge of writing for instruments with strong linguistic connotations and limited potential for blending. In 2019, you composed Semi alle Bestiole Salve for Azione_Improvvisa, with perhaps even a more challenging instrumentation. Can you tell us about the piece and how you approached this challenge?

In Semi alle Bestiole Salve, I imagined a situation where the linguistic potential could be disarmed starting from a rather particular acoustic dimension—something I hadn’t done, for example, in Ludica II. In Ludica II, the linguistic and connoted elements were more exposed. There was a kind of abrupt crossing of thresholds, but the aspects were quite clear in terms of sound mass. In Semi alle Bestiole Salve, the treatment was more atomistic. The three instruments—theorbo, accordion, and electric guitar, alongside live electronics (which is performed on stage with a lot of voice and small percussion instruments)—are very different from each other. I tried to imagine them literally as childlike instruments, playing in a park, getting dirty, throwing things at each other, grunting. This childlike and simultaneously animalistic dimension helped me greatly in defusing, at the level of small units, the linguistic potential of the instruments themselves. The title, derived as an homage to Sciarrino (who had asked me to write a piece inspired by a bestiary he had gifted me), also guided the writing to some extent.

For the theorbo, it was relatively easy. There are moments where I envisioned the theorbo lying completely flat on the ground—there are actually two different placements for the instrument in the piece—so the traditional practice of playing it simply isn’t there. Additionally, I initially considered working with the traditional practice of adjusting frets for microtonal tuning, but that didn’t quite satisfy me. I preferred to handle that aspect electronically instead.

Another challenge you’ve recently faced was writing for classical guitar, an instrument you initially felt almost repulsed by. What caused this initial disinterest, how did you approach composing Sans Dire, and how has your relationship with the instrument changed, if it has?

My initial disinterest came from the fact that I wasn’t fond of the image I had of the guitar—an image that’s admittedly false, and not particularly noble. I never felt attached to the world of classical guitar, and the concept of a classical guitar concert always made me skeptical in terms of the overall experience. That said, I’ve always found the guitar to be a wonderful instrument for describing the temporality of the “moment”—there’s something ephemeral about the guitar that has always intrigued me.

The other reason that distanced me was related to the topic of the song, in the sense of song device that uses the guitar. While I can appreciate current reflections on the song element, aesthetically, I feel terribly distant from it. I tend to avoid it, and many of the rhetorical aspects tied to contemporary reflections on songs don’t interest me at all. So, my relationship with the guitar was tied to these two factors. And of course, it’s also a complex instrument, not easy to approach. It seems accessible to everyone, but in reality, it isn’t. The phases of exploration are complicated, the technique is unique and intricate, and there’s the issue of its power. If I had to write a piece for solo acoustic guitar, I probably would have said no.

What eventually piqued my interest—aside from your involvement, as my interest in performers can completely change the nature of the challenge and my reflections on the instrument—was the fact that the guitar was amplified and paired with electronics. That allowed me to explore a palette of sounds through the magnifying lens of amplification and approach a different kind of dramaturgy.

There were many challenges. I wanted to create a piece with broad articulations, a piece with a lot of unspoken elements, full of gestures—gestures that soar into the air and lead almost nowhere, like clouds, but occasionally explode.

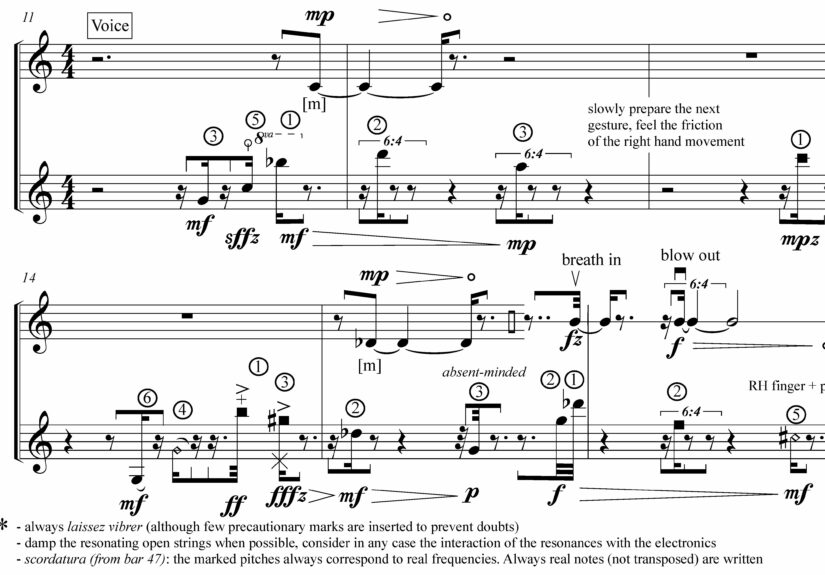

It was a work that brought me back to a gestural relationship with the instrument, very similar to one I explored in my piano piece Tre Nudi. A very bodily relationship with the guitar, which is not violated by invasive extended techniques—it’s truly embraced. I was interested in the movement of the hug, in how the right hand rises to perform bi-tones. That technique fascinated me, the raised right arm embracing the body of the guitar. And these articulations that become hyper-articulations with the augmentation of electronics, with these plucked sounds that are kind of marimbas made of strings through physical model synthesis. What also proved fascinating was merging these elements with the microtonal aspect of the guitar. The gestural aspect explodes in the piece with all the body actions tied to the guitar itself—something I didn’t expect to encounter but couldn’t ignore when it appeared, because it really gave three-dimensionality to the whole work in terms of meaning. The embrace wasn’t just a softening of relations between bodies, but a true affective element, with gestures that, while not inherently “guitaristic,” became so when holding the guitar.

When I received Sans Dire, I immediately felt that there was a lot of our personal relationship, our friendship, within the piece. It felt as though you were writing to me, not just for me. How does the person or ensemble you’re writing for influence your composition?

I have tried with ensembles several times and have failed in my attempt. By “ensembles,” I mean from medium ensembles and above, or ensembles with which I have no relationship—primarily institutional ensembles, with which there is a gain in terms of growth and maturity when working together occasionally, but they are certainly not my main interest. On the other hand, with the ensembles I work with regularly, where there are cycles of collaboration, different situations arise. Clearly if I happen to write a second piece, as happened with Nikel, but also, for example, with ensembles like mdi, with which I have collaborated for about twenty years, even without producing new pieces, there’s a continuous evolution in the interpretation of my music.

With small ensembles or soloists, the situation is quite different. I don’t like the idea of “writing for” someone, but rather “bringing the person I’m writing for towards something.” I enjoy staying connected with the people I write for during the compositional process. I’m always thinking about them, imagining them playing each sound. It’s no longer just about creating pieces, it’s about envisioning that specific person performing, shaping each sound as if they were playing it. This means that, almost immediately, you want to guide that person towards a specific place—this is very different from taking a passive approach, like my generation might have when writing for something like the Arditti Quartet, where you’re composing for a well-oiled machine with its own set of predefined qualities. When working with soloists, especially younger ones, I’m interested in this idea of building a prototype engine.

Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, but it always results in a very intense musical relationship with the people I collaborate with. I think of you, for example, and Matteo Cesari—two very different pieces were born from those collaborations. In Matteo’s case, I wanted to push him literally where he wasn’t, and I even sacrificed certain aspects of the piece just to say, “No, go there!” In your case, the process was much more about freely discovering the instrument. However, I also wanted to bring you to a heightened level of performative awareness, with a stage presence and a focus on every action on the instrument. This approach is highly classical, even elevated, and it requires an intense level of concentration.

When I mentioned that this piece began to reveal a kind of physical and gestural relationship with the body-instrument and with the exteriority of the body-instrument, the projection of the gesture of the body-instrument, it became clear to me that I was envisioning you performing those movements. That’s where I wanted to take you, whether I succeeded or not.

In addition to your compositional work, you are also the artistic and musical director of Opificio Sonoro, a music collective based in Perugia that you founded with Claudia Giottoli and Filippo Farinelli in 2019, and which now has 14 members, of which I am proud to be a part. What motivated you to create this group, and what does Opificio Sonoro represent for you today?

There were several motivations behind starting Opificio Sonoro. First and foremost, the desire to step outside of my own space. The work of writing is exhausting, and around the age of 40, I started to struggle with it particularly; I began to love it much more than before, but I also physically suffered from the isolation, because it is a work of extreme solitude. Another reason was the desire to share. I realized I might have something to contribute in terms of musical or artistic direction. There’s also a political aspect, in a sense. In Italy, there was a lack of ensembles that truly pushed the technical and interpretive quality to a higher level, and that saddened me. The challenges for Opificio Sonoro have multiplied since its inception. The project could have easily ended at least ten times, but it continued, and I will do everything in my power to keep it growing and evolving. At this point, my greatest ambition is to detach Opificio Sonoro from myself—not in the sense of leaving, but in giving it freedom. I do not want the other qualities of the ensemble to be overshadowed by an external perception limited to my figure, which, clearly, as the musical and artistic director, is today quite central and exposed.

I don’t know what the future holds, but the exciting part is that Opificio Sonoro is now a reality. In the last two years, the ensemble has grown exponentially—not only in terms of members, but also in the individual development of each musician. It’s now an established presence, and it’s up to others to take notice. That’s something beautiful, and we’ll see where it leads.

Would you like to share any of your upcoming projects? Is there anything involving the guitar on the horizon?

My future projects are always easy to predict, in the sense that I usually have very few of them. I’ve chosen to maintain a rather slow pace of production—my last piece took two and a half years to complete. This means that the expectations for new pieces are slower, in the sense that it is necessary to reawaken each time, hoping that it will be reawakened, the attention at the end of a project that has taken a long time, because in the meantime, obviously, other projects have been neglected. Right now, I have two works on the horizon. One of them, expected to premiere in April 2025, will be for electric guitar, saxophone, and electronics.

Is there anything you’d like to share with us, the new generation of guitarists?

There’s a young movement within the guitar world that is drastically different from what I knew at your age. To me, this is completely unexpected and, I have to say, miraculous. It’s the beginning of a revolution.

What I hope for is that you avoid the mistakes of the older generation of guitarists, which I feel was often passive in its relationship with composers, always saying yes to any claim of invention or search for invention. An openness that often came dressed in untouchable instrumental mastery, the oxymoron of rulers serving at the table. Instead, I hope you become selective and firm in redefining yourselves, together with others, and speak about your instrument in terms of its artistic potential, rather than just its technical potential—two aspects that can be quite far apart. Perhaps you’ll play less contemporary music, but in exchange, you’ll create an even richer repertoire. To do this, you must be free, as your world—like the contemporary music scene—has always been somewhat closed off. There have been figures who frequently sought to monopolize it. I’m referring particularly to the world of electric guitar, which is finally starting to breathe now. It’s crucial that it maintains this iconoclastic approach.

On one hand, give priority to content over the piece for the instrument itself—make the instrument a vehicle for expression, rather than a reflection of a supposed inventiveness. On the other hand, embrace iconoclasm, have the courage to do your own thing, to say no, and to make your own bets. This will give you a freedom, a freshness, and will finally open your instrument to the great classical repertoire, not just contemporary music, breaking away from genre limitations. Through you, we can finally start thinking in these broader terms, and I hope you’ll continue to push forward with your revolution.