Eclectic Valencian artist Joan Gómez Alemany (1990) boasts an extensive body of compositions. His works explore the musical process through extreme transformations, leading instruments to reveal unexpected facets, often in stark contrast to their traditional function. Despite this, his music remains focused and cohesive, successfully blending complex and chaotic materials with moments of great melodic expressiveness. This balance between innovation and tradition reflects his passion for painting and writing, as well as his relentless quest for new sounds.

Joan, thank you for being with us. Your catalog includes many works for guitar despite your young age. You have a direct approach: you experiment with tunings that often push the instrument’s limits, develop unique percussive techniques, and use common objects for preparations. Where does this approach come from? There is a quote attributed to Berlioz: “The guitar is a small orchestra.” I completely agree with him. The vast range of possibilities with this instrument, along with its timbral subtleties, makes the guitar one of my favorite instruments to compose for. My main instrument is the piano, which for me shares many connections with the guitar in terms of wide timbral possibilities, but the guitar has the advantage of being much lighter and without such a large or complex mechanism like the piano. This makes it far more adaptable for being transformed and expanded more easily and directly, turning it into a percussion instrument, a bowed instrument (like a violin), and of course, in its standard form, a plucked string instrument. These are three general approaches I’ve used in my compositions, and there are few instruments that offer this kind of versatility. For this reason, it’s the ideal instrument for timbral exploration, which is a common feature in contemporary music.

Have you ever handed the score directly to a performer without first personally exploring the instrument?

Well, I can almost certainly assure you that with the guitar, I’ve never done that. That’s because I have a guitar at home, and whenever I compose for it, I keep it by my side. To me, the best orchestration manual is having the instrument itself when you compose, so you can understand it and play it in its materiality. In my opinion, from a current sound conception, the instrument should not be an ideal and abstract entity that you have to imagine in order to hear it. This might have worked (and still does to some extent for certain people) when thinking of the instrument only in “pure intonations,” like notes, so you could compose for the guitar on the piano, focusing only on issues of fingering and register. I think this approach is very old and an heir of tonal music, and in today’s music (at least the most advanced), this way of thinking is completely outdated. For this reason, whenever I can, I use the instrument to compose. If I don’t have it, I ask the performer directly. The ideal is to combine both options, but sometimes that’s not possible. Fortunately, the guitar is an easy and affordable instrument to acquire (at least in Spain), which allows me to personally explore its techniques.

In your early works for guitar, Un nouveau morceau de musique surréaliste and L’arrivée (2018/2019), there are analogous materials. However, they are written for two very different instruments: the classical guitar and the electric guitar. In what ways did you find similarities, and in what ways did you perceive differences?

I find the idea you’re proposing very interesting. Conceiving the guitar as a small orchestra, rather than an essential instrument with distinct characteristics, sometimes blurs its limits. In a way, its stable and usual boundaries are erased, and instrumental techniques—or even the production of sound—are (we could say) deterritorialized. This allows us to “hear” (with some imagination) a contrabass pizzicato on a classical guitar, or a Tibetan bowl on an electric guitar, just to give two examples.

To answer your question more directly, I think it becomes clearer that when you approach these two instruments with the aforementioned ideas, it’s easy to understand how the differences between them blur, and you can find analogous materials. In the two works you mentioned, the percussive or noise element of the ensemble performing the piece is very present. For this reason, the classical and electric guitars share sounds that emphasize this noisier side. For example, muting the strings to perform various techniques such as scratches or highly percussive plucking. If these materials are amplified (as in the case of the pieces mentioned), it becomes quite difficult to tell whether they are being played on a classical or electric guitar. However, it’s also true that the instruments have their own inherent characteristics; in my view, the most obvious is the acoustic vs. electric difference. In this sense, to cite an example, with the electric guitar, using the jack as a “pick” or the white noise from the amplifier can create an entire world that’s impossible to achieve with a standard classical guitar.

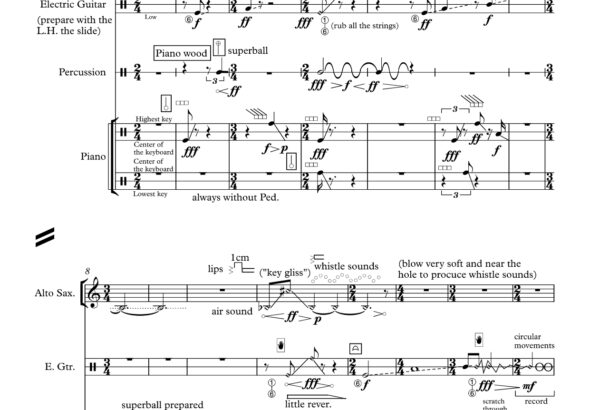

You highlighted the diverse possibilities of the electric guitar in your ensemble work TV (TeleVision) = TN (TransNacional) = TNT (Turner Network Television) (TriNitroToluene), a critique of the trash programs that characterize national television networks. This research led you to explore white and granular sounds, which you transformed into autonomous modules in Archive Delirium (2022). How did you approach the guitar in a chamber music context?

My approach to the electric guitar stems from the fact that I have the instrument at home, allowing me to explore it in depth. Specifically for TV…, given its complexity and the fact that it was a commission for the Ensems Festival, I decided to purchase the instrument to understand it in its materiality. It’s true that the first piece in which I used an electric guitar was L’arrivée, but that was just two minutes long and was selected for the Impuls Festival through a “call for scores” for the Nikel Ensemble. Since TV… was a different approach, being a nearly nine-minute work, when composing and creating a rich and varied language, it was impossible for me not to have the instrument in hand and rely only on reading scores, listening to audio, or reading books on electric guitar. That’s why I decided to purchase a guitar and explore all the sounds you mentioned—sounds that would have been impossible to fully understand otherwise.

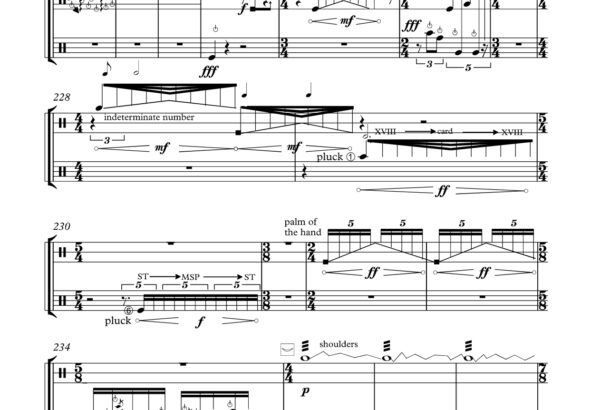

The search for white noise was done very intuitively, as were all the granular elements I achieved by practicing with the instrument using a highly investigative approach. Many techniques I didn’t know beforehand, even though I later realized they were present in various scores. However, because I didn’t fully understand them when I heard them, I couldn’t identify and recognize them. From that preliminary work with the guitar as a “solo researcher,” I was able to take the leap into a more complex chamber music approach with this instrument. In fact, it’s no coincidence that TV… opens with a roughly thirty-second guitar solo, as the instrument plays a significant role throughout the piece, and its sound influences the entire ensemble, “electrifying” it. It’s precisely the strong personality of the electric guitar, with its vast possibilities, especially thanks to the use of effects, that allowed its insertion into chamber music to blend seamlessly with the other acoustic instruments (even though they were amplified and there might have been electronic “tape” music).

The dialectic between the electronic and the acoustic has always fascinated me, and this stems from my deep interest in electroacoustic music and unique instruments like the electric guitar. Furthermore, in Archive Delirium, the use of the electric guitar in a chamber music context is so fruitful that even the other instruments, although acoustic, are equipped with their own pedalboards. Being amplified, these instruments can manipulate their sound in real time, creating an “electrified” effect with distortions, delays, reverbs, and the like. This generates a “delirium” (as suggested by the title) emerging from the sounds offered by the electric guitar.

While your ensemble compositions display a refined work on specific sounds, in Una tierra fragmentada (2020) and Un fragmento de tierra (2017), it’s the obsessive repetition of patterns and rhythms derived from traditional languages, like flamenco, that shapes the form of these works. Both pieces, written for quartet, deal with similar themes, as the titles suggest.

Yes, in these compositions, unlike the previous ones, I aim to highlight more the “characteristic or instrumental” side of the guitars. Both this choice and the opposite one, which is to eliminate any instrumental characteristics to deterritorialize the sound, are options I don’t consider antithetical. They depend on the composer’s interest at that moment and the aesthetic goals set for each composition. In my opinion, the greater the variety and possibilities in music, the more it demonstrates richness and knowledge of the art of sound.

Flamenco and Arabic music are genres I’ve always loved and have worked with in various compositions (such as Meta-improvisació, Azhan, or VIENTO del PUEBLO. Homenaje a Miguel Hernández). Generally, these borrowings or stylistic citations from other music are heavily “transfigured” and integrated into a contemporary music context, which tends to have a more internationalist style. The two guitar quartets are connected not only because their titles suggest a palindromic relationship, but more importantly because both works explore (we could say) a fragment of the characteristic music of a territory (Andalusia or Spain for flamenco, and Arab countries for Arabic music). However, the titles also indicate a connection with the “Land Art” movement (Michael Heizer, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Long, Robert Smithson, etc.), which inspires the compositions with its landscape constructions and geometric forms, influencing the motivic creation of the two quartets.

The use of more traditional elements and clear, repetitive patterns appears in both works, though it’s more evident in Un fragmento de tierra. This piece for classical guitar quartet transports listeners much more quickly into the flamenco soundscape than the electric guitar does. Typically, when the electric guitar has been used in flamenco, it’s to introduce rock or pop influences, creating a “fusion” style. This type of music doesn’t interest me; what I sought in Una tierra fragmentada was the opposite process—to bring the electric guitar closer to a flamenco sound, distancing it from its association with commercial music.

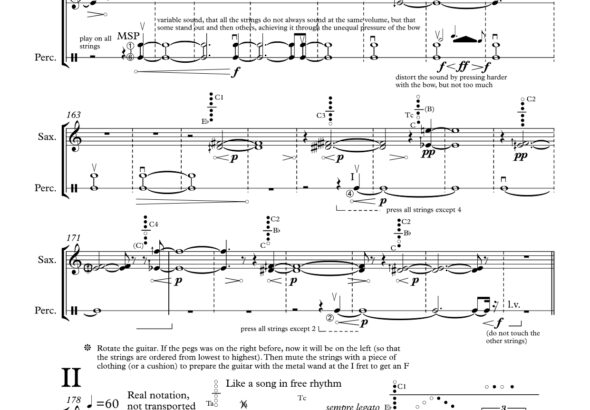

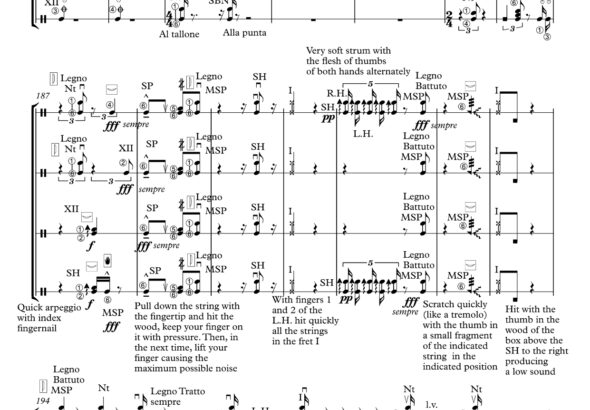

Your exploration of sound has often led you to transform the role of musical instruments into “tools” for achieving gestures, sonorities, and noises suited to specific contexts. I’m thinking of Azhan I (2018), for saxophone and percussion, where the guitar, placed on a table, undergoes various preparations and its strings serve as a resonance tool after a percussive gesture. This pursuit of noise as a sonic component is a recurring theme in your style.

I return once again to Berlioz’s quote: “the guitar is a small orchestra.” This instrument can offer an unparalleled palette of timbres (including both notes and noises, as well as their many transitions), making the guitar a sound source that, if I may say, transcends traditional guitarists, allowing its use by other instrumentalists, such as percussionists. I should remind you that I am trained as a pianist, and for me, the guitar has many connections to the piano. Therefore, I feel comfortable saying that I “play the guitar like a pianist” (though, of course, I’ll never reach the level of a professional guitarist).

In Azhan I, the percussionist uses the guitar with percussion-like notation, allowing the instrument to be played without the specific knowledge required of a guitarist (frets, specific pitches, pizzicato, finger techniques, etc.). This brings the guitar closer to other typical percussion instruments, like the flexatone (to imitate the glissandi that the guitar can produce), cymbals or Tibetan bowls (for harmonics, bell-like sounds, or the guitar’s multiphonics), or wooden boards (striking the guitar’s body with mallets). This array of techniques allows the music to go beyond the traditional sounds of notes and chords, exploring an almost infinite field we often categorize as “noise,” typically associated with various percussion instruments rather than tempered or traditional ones.

Many of the techniques associated with contemporary music come from instruments originally built to play perfect notes but have been decontextualized (or deconstructed) to create new sonorities, untethered from the tonal style and opening up new expressive worlds.

You’re not just a composer but also a performer, often playing the piano and regularly improvising. How important is improvisation in bringing your music to life? Is there a true connection between these two activities?

In my view, a performer (or at least someone who does not limit themselves to the strict meaning of the term) must go beyond simply playing a score. They should open it up as if they were recreating it, or be able to improvise within their own technique and style. For a composer (at least in my case), the process is often reversed, as composition frequently arises from improvisation with instruments themselves or from performing or listening to pre-existing works, which spark new ideas for composition. This shows that the distinctions between composition, improvisation, and performance are not irreconcilable or entirely oppositional. Rather, the boundaries can blur, creating interesting links between these activities (and others). For me, this is much richer and helps to understand music (or sound) from a holistic, global perspective.

That said, specialization is necessary, and it’s impossible to excel in everything equally: we all have limitations and must make choices. I started out as a pianist, but later dedicated myself to composition, though I had to give up performing because I couldn’t do both at the same time.

Would you like to tell us about your future projects?

As I write this interview in early August, I’m finishing up a piece that will be premiered on September 23 at the Ensems Festival in Valencia. It’s for saxophone, video, and electronics, commissioned by saxophonist Xelo Giner.

At the end of October, I have a work that will be premiered in Vigo and a few days later in Pamplona. For the first time, I’m including both a classical guitar and an electric guitar (performed on a table) in the same composition. The two guitars are used as percussion instruments, which is why the piece is for four percussionists. The other two also play other “strings” like a berimbau and a violin. The piece, which includes video and electronics, will be presented by the Vertixe Sonora Ensemble and is titled Para Vicente Gómez García, pictoescultura de luz y sonido. It will feature some of this artist’s paintings and sculptures, which will be connected to my music.

In November, the Lumina Ensemble saxophone quartet will dedicate my first monographic concert at the MACA Museum in Alicante, performing almost my entire repertoire written for saxophone (from the earliest in 2018 to the most recent). Like the guitar, the saxophone is an instrument I have at home, I really enjoy it, and I’ve devoted a lot of music to it. These are my upcoming projects, although I have others in development.

Thank you so much for this interview, which I found very interesting with well-thought-out and stimulating questions. A big hug!