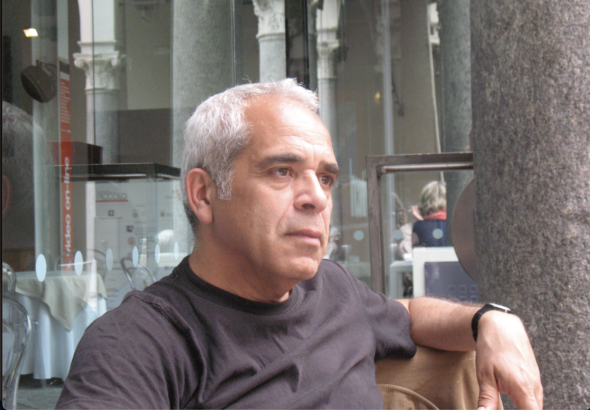

Gabriele Manca (*1957) is a composer and professor at the Conservatory of Milan.

His music has been performed by some of the most renowned interpreters: the Arditti Quartet, Klangforum Wien, Nieuw Ensemble, Elision Ensemble, Sergio Azzolini, Kees Boeke, Antonio Politano, Antonio Ballista, Elena Cásoli, Guillermo Lavado Lluch, Alter Ego, and conductors such as Emilio Pomarico, Beat Furrer, Ed Spanijard, and Zsolt Nagy.

He has been invited to give workshops and lectures at the Irino Foundation, Senzoku University Tokyo, Toho University Tokyo, Theatre Winter Tokyo, Tokyo College of Music, the Polytechnic of the Arts in Milan, the Italian Cultural Institute in Tokyo, the University of Melbourne, and the Catholic University of Santiago, Chile.

In this interview, we shed new light on his repertoire for guitar, his collaboration with Elena Cásoli, and the numerous textual references in his work.

You’ve always shown a strong interest in Xenakis and Bartók. What fascinates you most about their music, and do you think any of their ideas have influenced your own work?

That’s an interesting question! Yes, I often express my admiration for these two composers, who might seem far apart, but maybe only in terms of time. And even then, not by much… I’m always struck by the deep, physical nature of their music. Even though both are extremely sophisticated in their compositional techniques and thought processes, they manage to tap into something deeply rooted in sound, in how we naturally feel music. Xenakis, in fact, was fascinated by Bartók’s music because he found ancient musical traditions still alive in it, even connecting back to antiquity. This kind of archaic, almost primal spirit in their music-making is something you find in Xenakis too. That’s what attracts me—the idea of a way of feeling music (not just listening to it) that taps into the very core of human perception. Both composers reveal the profound depth of world cultures and the shared thread that connects them. As for whether their influence shows up in my own music, it’s hard to say without sounding immodest, but I’ll try. Bartók and Xenakis have shaped my musical world and values to such an extent that they almost define my understanding of what it means to make music.

You’ve written a lot for guitar over the course of your career. How did that start?

Actually, my very first piece for guitar and ensemble goes way back to when I was a young student at the Milan Conservatory in Giacomo Manzoni’s class. I think it was my first composition ever performed in a public concert. The piece was called Thema e Nachtlied, and it was performed at the beautiful Scuderie of Vigevano Castle. I don’t remember much about that piece, and I have no idea what became of it, but I do remember how I approached the guitar, which was the solo instrument. My first thought, which would come up again later in my career, was to “build” my own guitar. However, the real turning point for me came thanks to my friendship with Elena Casoli. In 1990, she asked me to write a solo guitar piece for a concert at the Ferienkurse in Darmstadt. That’s when In flagranti was born, a piece I still love today, despite all the years that have passed… Elena’s presence and, later, our close friendship have been the driving force behind all my guitar works. Elena Casoli isn’t just the extraordinary performer we all know—she’s also a person of great sensitivity and intelligence, always eager to explore and push boundaries, even in the most unlikely directions. My musical and intellectual debt to her is huge, and it goes far beyond just the guitar.

What were the main challenges you faced as a non-guitarist when writing for guitar?

There weren’t any particular challenges. Every instrument presents its own set of difficulties, but those challenges often become the very things we cling to for support. In the case of my first real piece for guitar, I clung to the idea of almost radically rethinking the instrument itself. One aspect I wanted to explore was the dynamic nature of the instrument, its “presence” in space.

At the same time, I didn’t want to, as I never do, deny the instrument’s nature. The guitar sounds like a guitar. However, one thing I have avoided in almost all of my guitar pieces is polyphony and counterpoint, which I have only tackled in my own way in “Luogo dell’incendio,” which I’ll discuss shortly.

Your classical guitar pieces seem to continually mix elements that eventually return to their starting point. In Flagranti appears to open up this long exploration, culminating in 2002 with Convulsive Space, a much more compressed piece in time that leaves little breathing room for the performer.

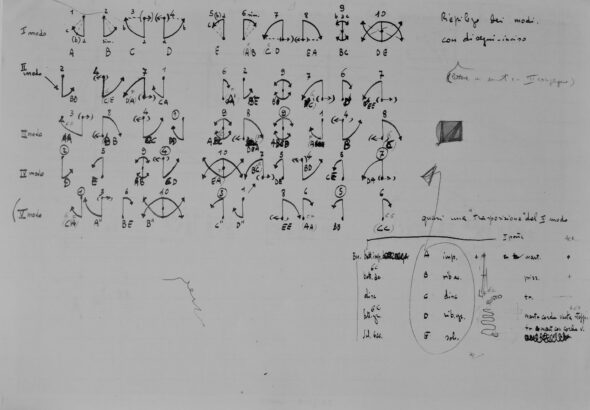

In In Flagranti, which then contracts in an extreme way in Convulsive Space, I wanted to approach the guitar by creating a sort of choreography of bottleneck positions. Before producing notes, harmonies, or modes, I envisioned a kind of dance for the left hand, a dance that would consequently produce a chain of harmonies, articulations, and explosions. The legend of the piece describes the “words” of this dance, which I organized into a kind of syntax that precedes the sound and gives it its necessary placement. Indeed, in these works, an irregular spiral leads to a negation of meaning (vector) and sense (significance) that still satisfies me. Paradoxically, the main body of the piece, both the first and second parts, could start from any point. Perhaps, unconsciously, I was laying the groundwork for the fixed ideas of these years: a different concept of form and listening. I would also say something that goes against form, to quote Tadeusz Kantor. Form is something that isolates, something that stands apart. And I don’t see music as something “isolating” or isolated.

I also attempted to “place” In Flagranti within a disorienting framework. Thus was born Corpo e ombra, a landscape for In Flagranti, for guitar and ensemble.

I must also say that In Flagranti has enjoyed some success among heroic guitarists who had the courage to tackle a possibly off-putting, necessarily complex score at first glance. I am deeply grateful to them. I think of Geoffrey Morris, an extraordinarily talented Australian guitarist who also recorded the piece on a beautiful CD; and Diego Castro, a brilliant guitarist and researcher with a powerful and deep sound who has performed the piece many times.

In 2009, you explored the electric guitar with Luogo dell’incendio. How did this piece come about, and what differences did you perceive between the two instruments?

Luogo dell’incendio was a commission from the Biennale Musica. The performer and dedicatee is Elena Casoli. The other dedicatees are the Selk’nam people and Lola Kiepja, the last witness of this ancient culture. Here is the text I wanted to include in the score:

“Of the Selk’nam people, otherwise known as the ‘ona,’ only a few shamanic songs remain. The last witness, a shamaness, died in her nineties in the 1960s in the far south of Argentina after leaving some of the songs she learned in her youth on tape for the American scholar Anne Chapman. The violent ‘holocaust’ of the nomadic civilization of Tierra del Fuego, which the old shamaness stubbornly preserved in memory, was swift, caused in just a few years by European hunters of men, recruited by landowners to ‘clear’ the land. The ‘Place of the Fire’ is the barren place where only the echo of a swift and definitive horror remains.”

In writing this piece, I tackled an idea of counterpoint that I had always tried to avoid. In one section, I aimed to create a kind of independence of the six strings—metric, modal, and attack independence. Each string follows its own somewhat autonomous path. The electric guitar proved perfect for this purpose, particularly because of its ability to manage resonances and sound durations more freely. I believe I wrote a fairly challenging piece, but not beyond Elena Casoli’s skill.

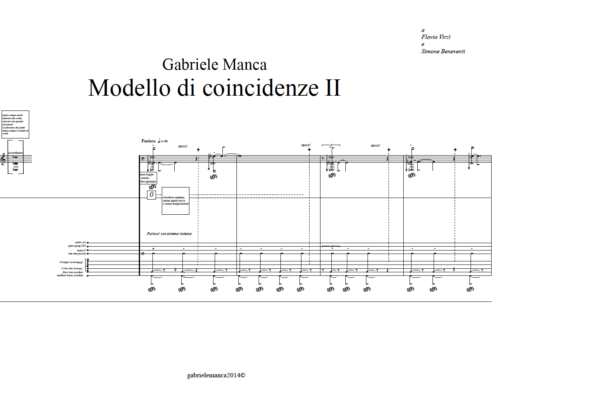

I also used the electric guitar in two other important works for me: Modello di coincidenze I and Modello di coincidenze II, which are part of a cycle of three that I hope to complete, for electric guitar and percussion.

Many of your pieces, from solos to duo and ensemble works, have been performed by Elena Casoli. How has your collaboration with her developed over the years?

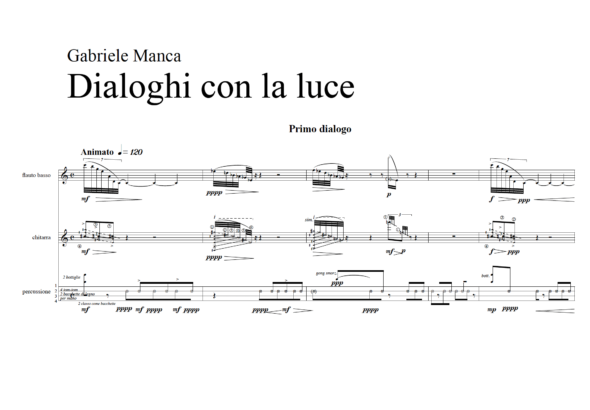

I’ve talked about Elena before, but I’ll never tire of doing so. She has always been at the forefront of my chamber music compositions. I think of Movimento forzato for guitar and flute in G, or Dialoghi con la luce for guitar, flute, and percussion. And there’s also Treppenwitz, a kind of opera without singers or text, made up entirely of sound, where Elena Casoli’s guitar (including electric guitar) and Antonio Politano’s recorders were the two main performers on stage. The other instruments in the ensemble were completely invisible. Among many other pieces, I would also mention Opus III and IV for the films of Walter Ruttmann, for guitar, accordion, recorders, and electronics.

You have been teaching at the Conservatorio di Milano for many years. How has your approach to teaching changed over the years, and especially, how have the students changed?

I’m not sure how to answer that question precisely. The truth is, my teaching approach aims to be very “fluid,” so I can say it changes with each student. At least, I hope it does! After many years of teaching, I still wish to learn how to help students write their own music well. It’s not easy at all. But this has always been my main goal.

I’m not sure if students have changed, except in the way individuals in front of me have changed. It seems to me that some approaches to creation have indeed evolved in some cases. Perhaps many young people have moved away from certain formal or organizational abstractions, from an out-of-time way of thinking, to dive more directly into sound, the instrument, and temporality. I find that very exciting.