Javier Torres Maldonado (*1968) is one of the most representative Mexican composers. Throughout his career, he has received numerous awards, including the Queen Elisabeth, Alfredo Casella, Prix des Musiciens, and significant commissions such as the Commande d’État and the Ernst von Siemens/Klangforum. Currently based in Italy, he teaches electroacoustic composition at the Milan Conservatory. His music is the result of a continuous exploration between the “natural and the artificial,” often making use of new technologies as auxiliary tools in compositional craftsmanship, creating entirely novel sonic synergies. His passion for the guitar has led us to delve into his works dedicated to the instrument, allowing us to closely explore every stage of his career up to the present.

Javier, thank you for accepting our request. Your career boasts a long path of study and experimentation. It’s interesting to note that the guitar has been present in your works since your student days. Your Suite, in fact, dates back to 1991. What was your first encounter with the instrument like?

Thank you for your interest; I’m very pleased to accept the invitation. I’ve always loved the guitar, ever since I was a child; in fact, along with the piano, it was the first instrument I played. My Suite from 1991? Incredible! How did you come across that strange piece?

I removed it from my catalog many years ago! I was probably sixteen when I wrote it; I don’t remember anymore…

For me, starting to play the guitar was natural, as it’s almost a national symbol in Mexico. My father (who was a veterinarian but also studied piano at the National School of Music of the National Autonomous University of Mexico -UNAM-) introduced me to music. When I still lived in Chetumal (Yucatan Peninsula), we often visited one of his friends, who was a guitarist and played Bossa nova and various other traditional genres splendidly: I learned a lot from him by listening to him play.

At the age of thirteen, I moved to Mexico City to enroll in violin at the National Conservatory and shortly after also in guitar. However, due to the demands of violin studies and the fact that I spent a lot of time on my early composition attempts, my academic path on the six strings was limited to four years during which I tackled the (didactic) traditional repertoire: all the volumes by Sagreras, studies and preludes by Brouwer, pieces by Tarrega, Villa-Lobos, but also some suites by de Visée, Weiss, and later Bach.

Although interrupted, I continued to explore pieces from the traditional repertoire whenever I could find free time. Furthermore, during summer visits to my parents, I often played Bossa nova with my father’s friend and other musicians – which, among other things, allowed me to buy a better violin.

Unfortunately, I had little contact with avant-garde guitar music of that time: the teachers I studied with had very traditional thinking, not all composers wrote for guitar (it’s always a challenging instrument if you’re not familiar with it technically). It was only later, when I started studying composition at twenty-one, that I was able to access some pieces from the modern guitar repertoire, discover the incredible resources that the instrument offers, and how it is, in fact, projected into the future.

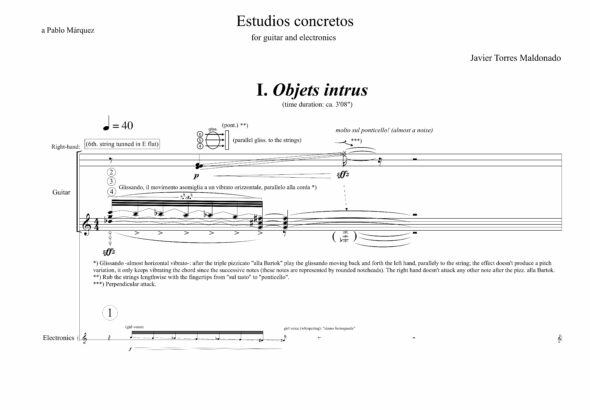

In the “Estudios Concretos” a work in three movements (Objets intrus, Crisscrossing (“the bells”), Acuática) from 2017, you utilized electronics with the guitar in constant dialogue with it. How does the working method change when the electronic aspect is added as part of the compositional process?

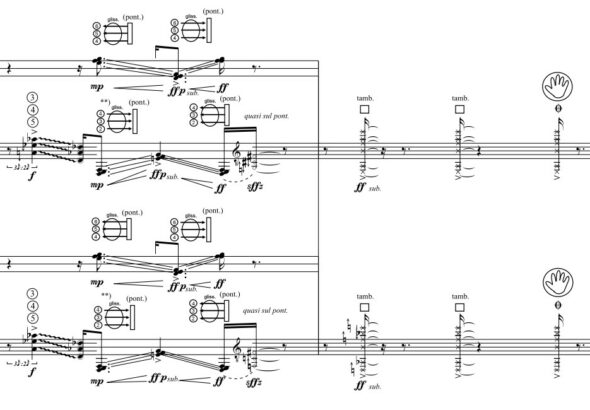

The Estudios Concretos are very particular, even compared to other pieces for solo instrument and electronics that I have composed because the basic idea – especially concerning the first two studies – is to create concrete music where sonic objects and compositional processes are largely the result of a global association of both sound sources: sounds from reality and those produced by the guitar. For example, in the first study, Objets intrus, I explored various techniques and levels of association of the sonic objects used (spectral or figural fusion, gestural complementarity, spectral distribution, etc.). The use of a child’s voice (that of my daughter when she was a child) emerges as one of the sonic elements that can be associated with a different meaning from the rest of the resulting events and, in fact, dissociates from them in many moments. The formal organization consists of five short juxtapositions of basic materials: figures that imitate vocal inflections, a vortex of irregular rhythmic impulses, a microcosmic material growth obtained through granular synthesis that includes, by association or dissociation of gesture, new sonic objects (“intrusive objects” indeed: birdsong, whip in the air, crystals, and other materials breaking…). The piece concludes maintaining the idea of microcosmic fragmentation, but this time does so by constantly altering the speed of reading of concrete sounds, so that an ascending glissando occurs preceded by the same gesture in the highest register of the instrument, through which the micro-fragmentation of the described material is imitated, thanks to a particular technique.

The other two studies present their own characteristics: the second associates metallic and percussive objects with the particular sound of the fourth and fifth strings crossed over each other, as well as percussive techniques on different parts of the instrument and on the strings, while the third is still different because the aquatic sounds proposed in the electronics are associated with objects of different sonic nature: the guitar overlaps them by joining the resonance of some unisons (double strings from which natural harmonics are often obtained) and more traditional instrumental figures. At the end, the idea of enlarged microcosmic surfaces is resumed, and everything is interrupted by the unmistakable sound of a large water bubble.

Would you like to hear about your partnership with the Argentine guitarist Pablo Marquez, who often appears as the dedicatee and interpreter of your guitar pieces?

As often happens with composers regarding the instruments they play and know the repertoire of, personally, I had a sort of creative “block” that prevented me from considering the idea of writing for guitar and violin. It was thanks to my friendship with Pablo Márquez that I overcame it; his insistence and interest in my music led me to initially work on the diptych Espira I, Espira II, where the guitar is the protagonist. It was the beginning of one of the most beautiful collaborations I’ve had with a performer.

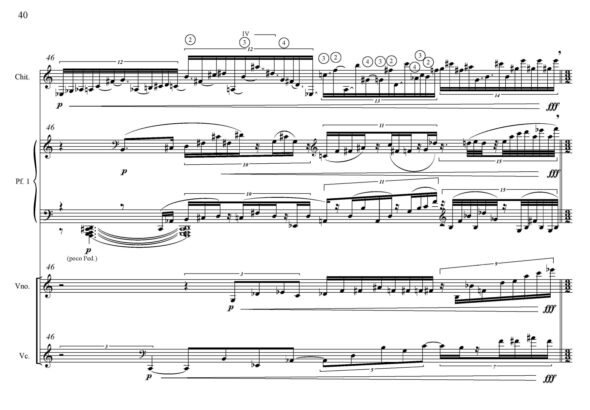

How about the recent double concerto for two guitars and ensemble Fénix (naturaleza visible)? It’s a very ambitious and extensive work. Would you like to discuss it?

The piece was commissioned by the Ensemble Phoenix Basel and the Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (FONCA) of Mexico and is the result of my collaboration with Pablo and Maurizio, exceptional musicians. It was an idea I had for a long time: I wanted to explore microtonal sounds on the guitar resulting from a multidimensional compositional system that starts from a fragmented use of expansions and contractions of materials not exclusively polyspectral: it was impossible to achieve the results I imagined with just one guitar. The piece had to last at least 25 minutes, and even then, I was already thinking of three contrasting movements; so I talked about it with Pablo and Maurizio, and the idea was proposed to the wonderful Ensemble Phoenix on the occasion of the world premiere of the Concrete Studies, performed by Pablo, which took place at the Gare du Nord in Basel.

The piece originates from different ideas, some of which are true constants in my music, particularly those concerning the intention to establish a connection between sonic objects from reality and their manipulation through processes of artistic invention, which depend on various transformations, and whose result could be compared to “imaginary chemical reactions.” These reactions give rise to contrasting musical elements, whose arbitrary and expressive deformation nevertheless maintains perceptible links with the basic sonic objects. Regarding the title of the work, I can say that the relationship between basic material and formal unity occurs through distancing processes (true perspective games) applied to the original objects. At the end of each transformation cycle, the materials return with a different brightness, as a phoenix would from its own ashes. The project was immediately embraced by the ensemble, and despite the difficult period due to the cancellation of many concerts because of the health emergency (it was impossible to perform it publicly in Switzerland and Mexico), we managed to turn it into a recording production (LP) that should finally be released in the autumn of 2022: it’s a truly wonderful recording. The contribution of both performers to perfecting some of the explored techniques was fundamental, and their suggestions enriched some passages of this score. The interpretation of the soloists and the ensemble, directed by Jürg Henneberger, is a very important document for my music, which transcends, thanks to the beauty of its result, the implicit limits derived from listening to a recording. The piece is divided into three contrasting movements; among the basic materials, we find the open strings of both guitars (each with a particular tuning that includes different microtonal pitches), their respective harmonics (natural or multifonic), the transcription of the sound of a crystal glass, different “deformations” of it, and some chord transformations from Scriabin’s Vers la flamme. The first movement presents some of the transcriptions of the basic sonic object almost literally; however, it’s difficult to deduce from listening that this material comes from a crystal glass, so the adopted title is Del cristal subliminal. The guitar tunings allow a particular exploration of different sounds depending on the natural harmonics and multifonics, as well as different types of rasgueado, not only the one from flamenco but also those assimilable to traditional Latin American music, like the Mexican huapango, and other techniques belonging to my music, such as various stopped sounds used in bowed instruments and naturally on the guitar. The second movement is titled Simple because the gesture that characterizes it is indeed very simple: it consists of different sequences of the pitches corresponding to the open strings of both guitars, initially adding those of the piano (played in the string bed) and later those of the violin, viola, and cello. Despite its delicacy, it’s actually a movement built with “raw materials.” Besides the sounds of the open strings, others obtained by playing with the other hand behind the “capo” are juxtaposed; also, quick hand gestures on the vibraphone are added. Towards the end of this movement, a passage alludes to the “visible nature” of the material: except for the piano and the two guitars, each of the instrumentalists plays a crystal glass. In this movement, the two soloists move behind the ensemble, creating a distancing effect that constitutes a plane on which the actions of the other performers add “ripples.” The third movement explores materials related to Scriabin: during the working process, I noticed that some transpositions and expansions of the transcription of the resonance of the sound of the crystal glass, by chance, approached some chords present in Scriabin’s Vers la flamme; that’s why Docteur Mystique (d’après Vers la flamme de Scriabin) is the title of the third movement.

Among the chamber music works featuring the guitar in ensemble, there are Espira I and II (2005) and Rosa Mutabile (2010), which feature the presence of a trio and a duo, like two different ensembles in dialogue with each other.

In Spanish, the term “espira” refers to the curved line of a spiral. The title alludes to the fact that sometimes the direction of both movements tends to precipitate into a sort of vortex within which musical figures condense. When I started working on this piece, I still remember that one of the aspects that interested me the most to explore was the pairing of the guitar with the piano, considered difficult to handle by many composers; their sound is complemented by the presence of a violin and a cello.

Rosa mutabile has a particular ensemble: flute, viola, guitar, bass clarinet, and percussion. These instruments are divided into two small formations because it was written for two Mexican ensembles that were to perform it at the “Puentes” festival in Madrid: Duo Duplum (clarinet and percussion) and Ensemble Espiral, for which I chose a trio: flute, guitar, and viola (with the guitarist being the Mexican Pablo Gómez Cano). It’s a cycle that unfolds in four short movements. The idea came to me after reading a poem contained in Federico García Lorca’s wonderful drama, Doña Rosita la soltera o el lenguaje de las flores, where the writer refers to the four phases of a flower created by Rosita’s uncle: a rose that lives only one day and changes its state according to the natural variations of sunlight intensity or its complete absence.

The poetic images described by Lorca can be summarized as follows: 1. opening in the morning (red as blood); 2. maximum opening at noon (bright and hard as coral); 3. at sunset, while the little birds sing and the evening “fades into the violets of the sea,” it becomes white; 4. in the night, it gradually fades away as the stars advance, the winds calm down, and the night plays its “white metal horn.”

The fact that two ensembles were to perform it fit very well with the research on the use of space (which I continue to develop even today): dialogues, oppositions, and spatial overlays follow one another throughout the four movements.

For several years, you have been living in Europe, and part of your musical education has taken place here. How do you judge the panorama of contemporary music here and in Mexico?

The panorama of contemporary music in Europe is vibrant and highly stimulating. There are many composers and musicians who embrace avant-garde music and actively circulate new ideas from one country to another in a wonderfully dynamic manner. Unfortunately, for some time now, resources allocated to new music have been progressively reduced due to a shortsighted, unvisionary, and ideal-less policy.

I believe it’s necessary for those responsible for the artistic direction of festivals, those who manage institutions, and important musical entities to have more courage and awareness that the fear of the new is merely a result of ignorance and conservatism. This can lead, at best, to the imposition of inconsistent trends and, at worst, to programming works composed half a century ago. We must strive to discover the new.

In Mexico, the panorama has changed significantly compared to when you were a student, and I must say that there have been many years when the investment in resources, not only in contemporary music but in all music, has been consistent and extraordinary. This has produced remarkable results that unfortunately, in the last four years, since the direction of almost all of the country’s most important cultural institutions changed, are rapidly dissipating. However, there are still many musicians and composers who remain very active not only locally.

You have taught over the years at the conservatories of Alessandria, Parma, and Milan. How do you see yourself as a teacher, and how important is this activity to your identity as a musician?

Teaching is for me a second vocation and it is not limited to the institutions where I work, as I am often invited to give masterclasses and lectures abroad in prestigious contexts. I believe that one can be a good teacher only by fully and at a high level practicing the craft they intend to teach.

Originally published in Guitart n. 108