The artistic collaboration between Maurice Ohana and Abel Carlevaro is one of the least known of the 20th century. Despite Narciso Yepes being a reference for the composer, the Uruguayan guitarist played an absolutely important role throughout Ohana’s entire career. It’s a story spanning over thirty years, from which an unperformed Concerto and a piece, “Estelas,” have emerged, forgotten by the world of the six strings. The archival work of Alfredo Escande, a disciple and biographer of Abel Carlevaro, has allowed us to analyze step by step all the vicissitudes that led two symbols of the 20th-century guitar world to have such a special affinity.

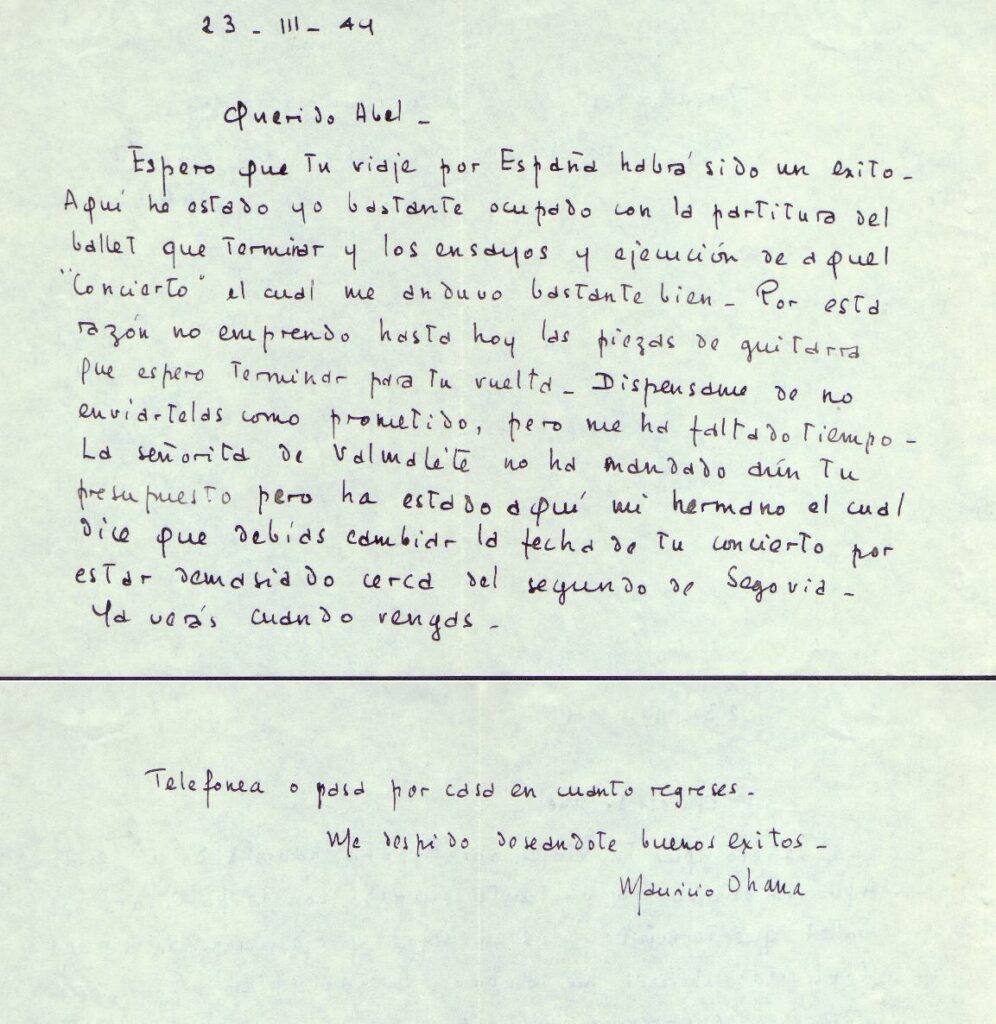

It all began under casual circumstances: Alberto Ohana, during a train journey, met Abel Carlevaro and spoke to him about his brother, the composer and pianist. It is not yet clear when Maurice Ohana and Abel Carlevaro first met; most likely, it was in 1948, the year when the latter arrived in Paris for the first time. There is no evidence of their meetings, but a first letter dated March 23, 1949, suggests that the two artists had a clear intention to collaborate:

“Dear Abel, I hope your trip to Spain went well. I am quite busy with the part of a ballet to finish, with rehearsals, and with the performance of that ‘Concerto,’ which is progressing very well. For this reason, until today, I have not been able to work on the pieces for the guitar, which I hope to finish upon your return. I apologize for not sending you the part as I had promised; I had little time. Miss Valmalète has not yet sent me a quote for you, but my brother came here, and he says that you should change the concert date because it is too close to Segovia’s second concert. We will discuss it when you come. Call or stop by the house as soon as you return. I greet you, wishing you all the best. Mauricio Ohana.”

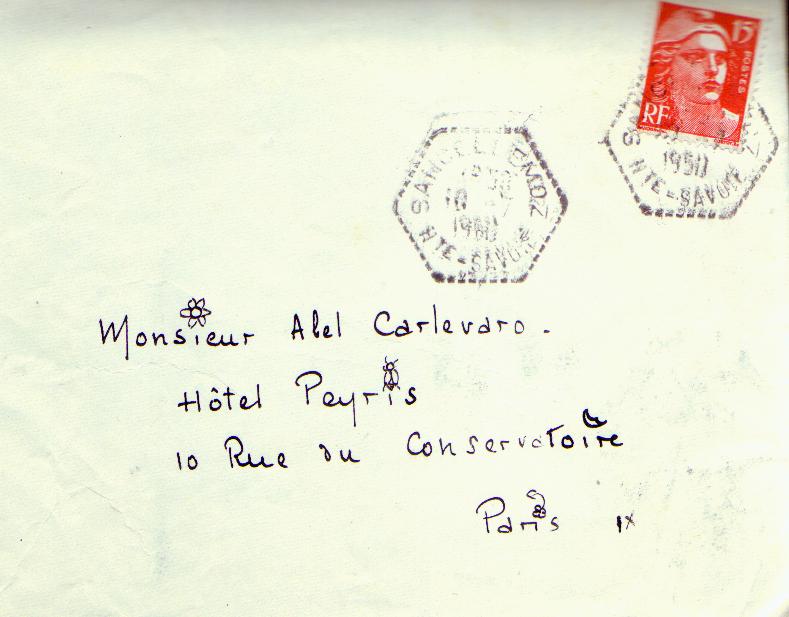

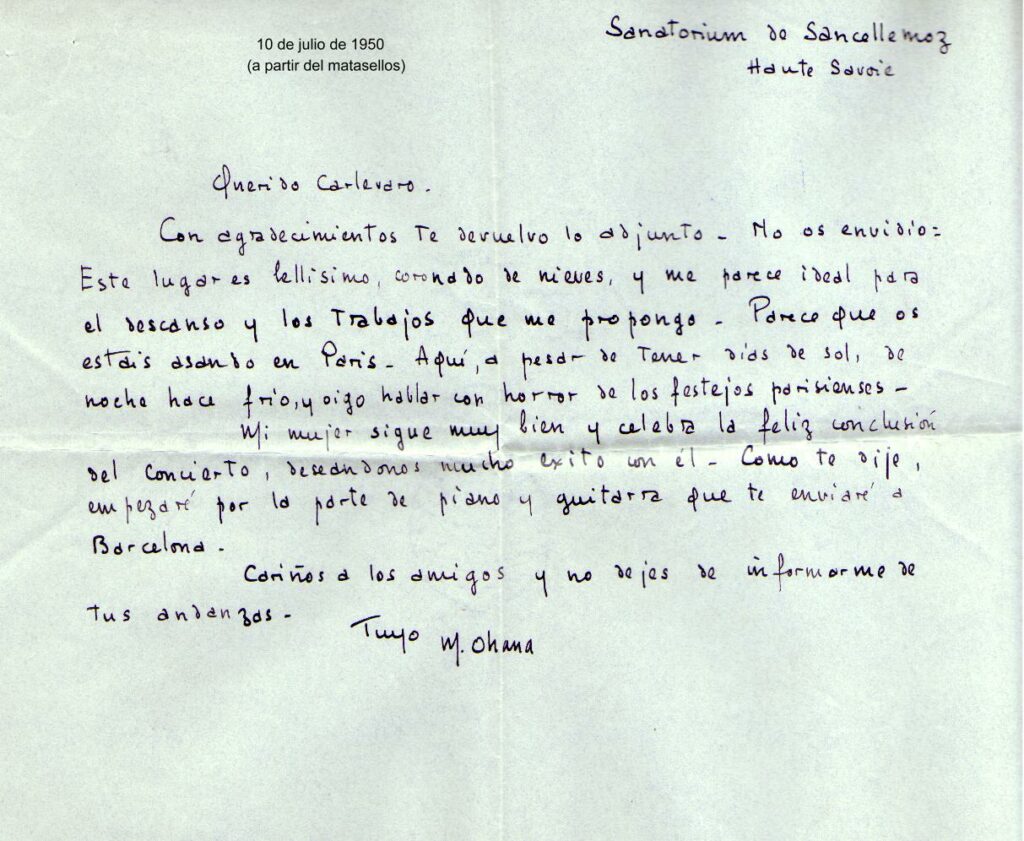

When Carlevaro moved to Paris in 1949 at the Hotel Peyris on Rue du Conservatoire, the contacts between the two artists became frequent. Several letters from 1950 show that they were not only working on a Concerto for guitar and orchestra (with a special dedication: “Para Abel Carlevaro, qué tiene manos de faraón” – “For Abel Carlevaro, who has hands of a pharaoh”), but the second movement was already completed. On April 28, a reduction for guitar and piano was performed in Paris, confirmed by various sources, including La Mañana in Montevideo and a BBC correspondent in the French capital, who described the event. The guitarist himself confirmed this in an interview with Gonzalo Solari published by Guit Art in 1999. Despite Carlevaro leaving Paris to go to Barcelona, the two musicians continued working on the project. In a letter from July 10 of the same year, Maurice Ohana wrote: “[…] My wife is very well and celebrates the successful completion of the Concerto, wishing us the best. As I was saying, I will start with the part for piano and guitar, which I will send to you in Barcelona […]”.

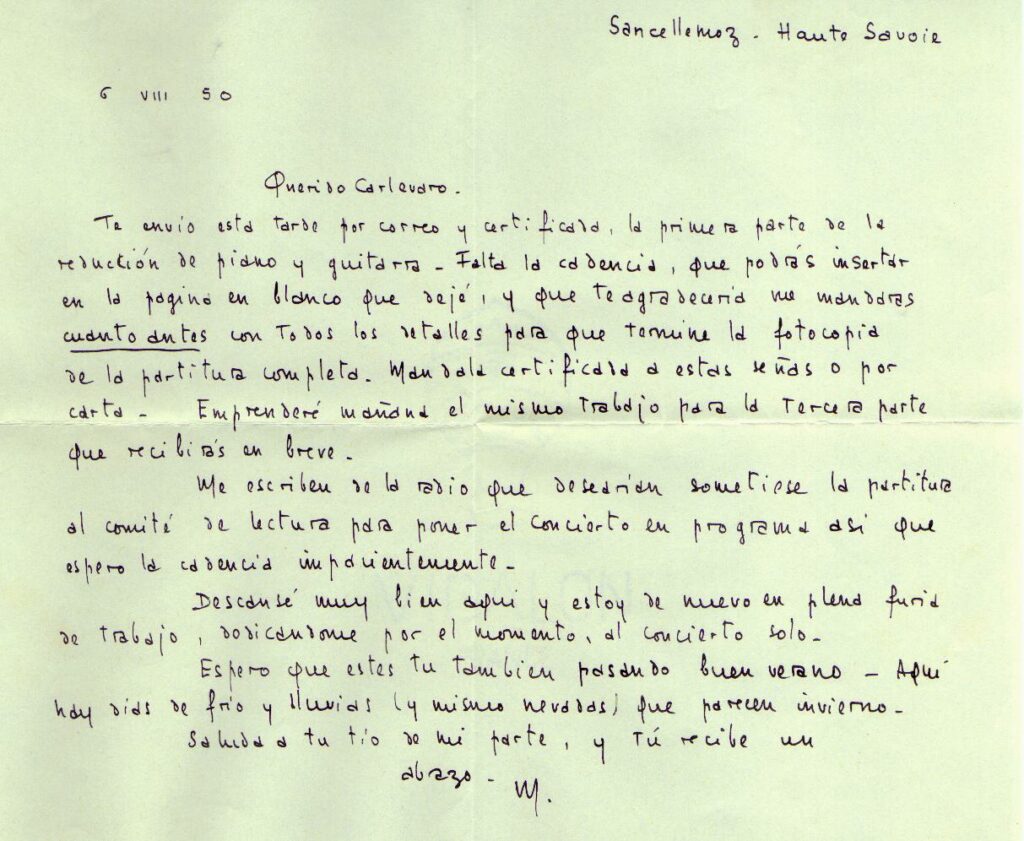

Everything was practically ready for a final review, leaving room for the cadenzas; the composer wanted this task to be carried out by the performer. On August 6, Ohana sent a letter with the reduction attached: “Dear Carlevaro, I am sending you the first part of the reduction for piano and guitar. The cadenza is missing, which you can add on the blank pages that I have left, and I would appreciate it if you could send it to me as soon as possible with all the details, so that I have the complete part. Send it to me certified at this address or by mail. I will start the same work for the third part tomorrow, which you will receive shortly. They write to me from the radio that they would like to submit the part to a reading committee to add the Concerto to the program, so I eagerly await your cadenza. […]”.

The revision didn’t take long to arrive, although the attachment with the cadenza was missing, probably due to a lack of time between travels, or perhaps because the Uruguayan guitarist hoped to meet the French composer again in person.

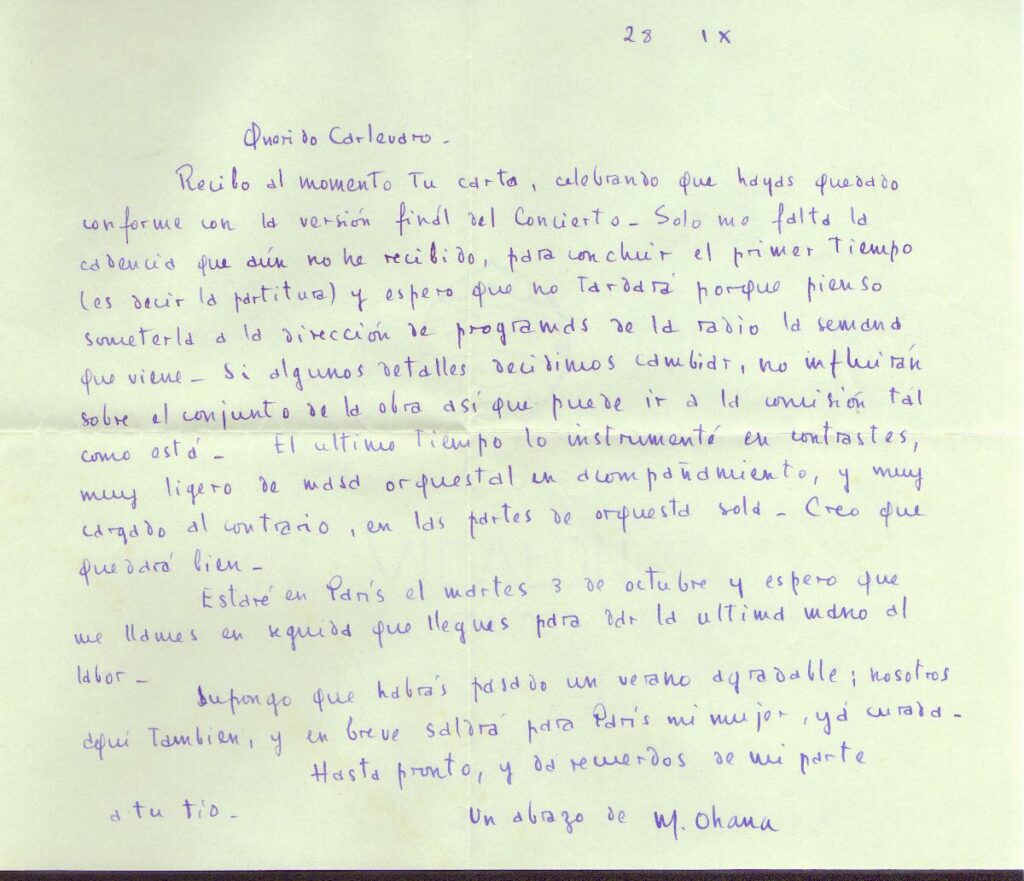

On September 28, Maurice Ohana wrote: “Dear Carlevaro, I have received your letter for the moment, and I am pleased that it remains consistent with the final version of the Concerto. Only the cadenza is missing, which I have not yet received, to finish the first movement (that is, the part), and I hope it won’t be delayed because I intend to submit it to the radio program direction next week. If there are details to change, they will not affect the whole, so everything can be sent to the committee as it is. I orchestrated the last movement based on contrasts, very light in terms of accompaniment and very dense in the ensemble parts. I think it will be beautiful. I will be in Paris next Tuesday, October 3, and I hope you call me as soon as you arrive to give the final revision to the work […]”.

The issue of the cadenza became a problem that led Maurice Ohana to insist often on receiving the drafts as quickly as possible. When Carlevaro learned that he had to return to South America, he tried every means not to leave Europe without having premiered the Concerto. However, a logistical problem arose: who would cover the travel costs from Barcelona to Paris for rehearsals? Considering the difficulties, Carlevaro asked the composer to travel to Barcelona to make the final adjustments to the piece.

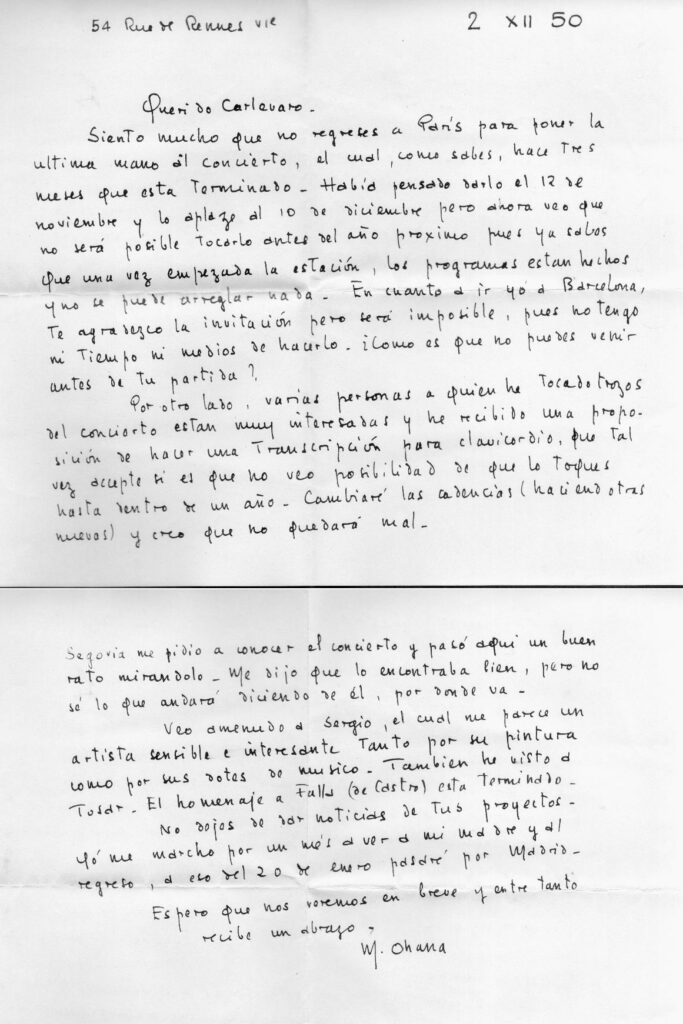

In a letter dated December 2, Ohana expressed all the challenges of the moment, not hiding a certain impatience: “Dear Carlevaro, I am very sorry that you are not returning to Paris to give the final revision to the Concerto, which, as you know, has been ready for three months. I had thought of the date of November 12 and had to postpone it to December 10, even though now I see that it will not be possible to perform it before next year, and you already know that once the transmission starts, the programs are ready, and nothing can be changed. Regarding the possibility of going to Barcelona, I thank you for the invitation, but it will be impossible; I do not have the time nor the means to do so. What does it mean that you cannot come before your departure? On the other hand, several people to whom I have played sections of the Concerto are very interested, and I have received the proposal to transcribe it for harpsichord, which I would accept if there were no possibility of you playing it within a year. Segovia has asked to see the Concerto and has devoted some time to reading it. He told me that it seems like a good piece of work, but I do not know how it will actually end. […] Keep me updated on your plans. I will visit my mother for a few days, so I will be in Madrid on January 20 […]”.

As we know, Andrés Segovia, far from any repertoire with a flamenco touch, never played any of Ohana’s works, especially after the composer’s choice to write for the ten-string guitar, an instrument to which Segovia had reserved many criticisms. When Carlevaro’s return to South America was confirmed, the organization of the event experienced a phase of stagnation. It was perhaps the most challenging moment for the two musicians, who tried in every way to find a meeting point, unfortunately without success.

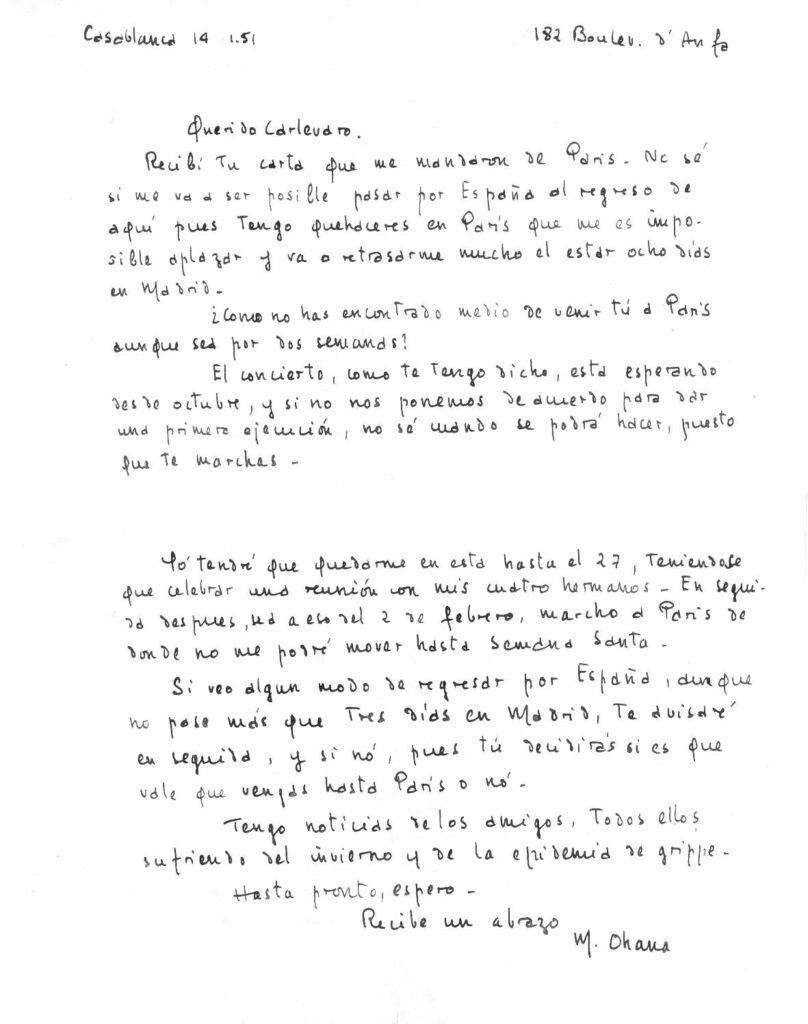

From Casablanca, on January 14, Maurice Ohana wrote: “Dear Carlevaro, I received your letter sent to me from Paris. I don’t know if it will be possible to pass through Spain on my return because I have commitments in Paris, and it is impossible for me to move them. It is too late if I decide to stay in Madrid for eight days. Why didn’t you find a way to come to Paris even for just two weeks?! As I told you, the Concerto has been waiting since October, and if we don’t agree to have a premiere, I don’t know when it will be possible, considering that you are leaving. […] If I find a way to return to Spain, even if I shouldn’t spend more than three days in Madrid, I will let you know immediately, or you can decide if it’s worth coming to Paris or not […]”.

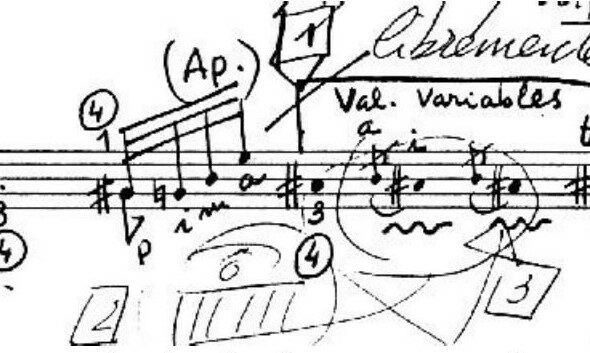

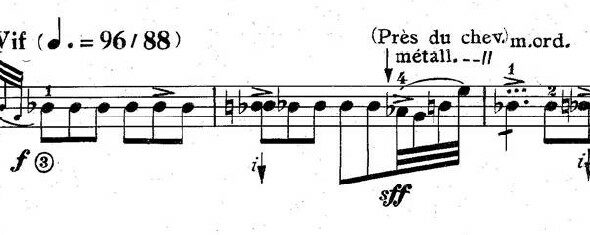

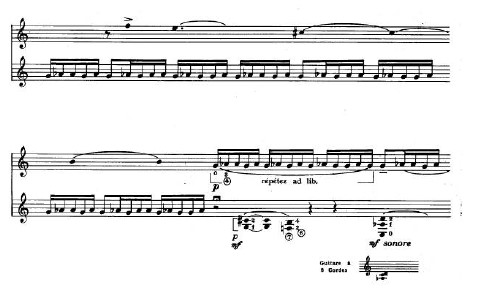

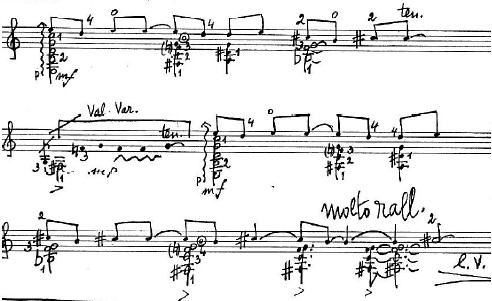

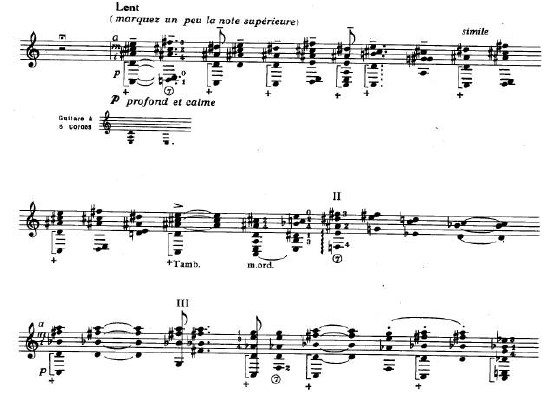

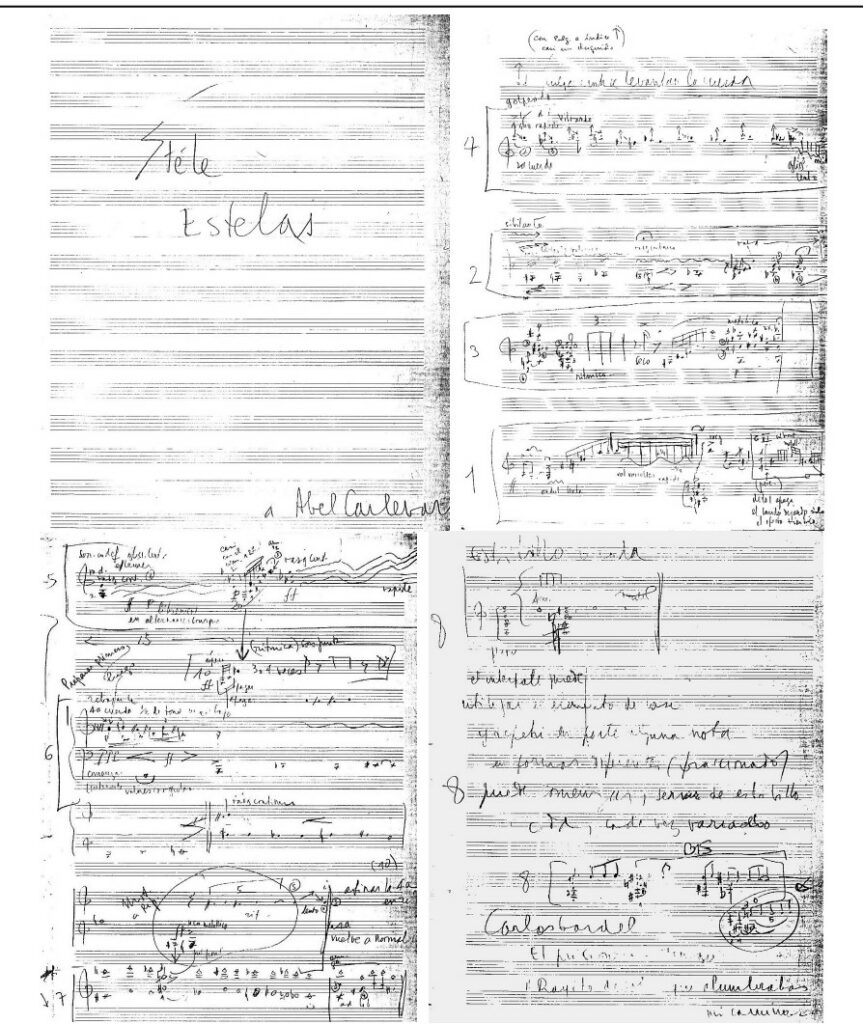

Carlevaro tried to convince Ohana with a final letter before his return. The last epistolary contact between the two musicians, on January 31, is a farewell that leaves little doubt: “Dear Carlevaro, I received your letter, to which I believe I have already responded, leaving open the possibility of my possible passage to Madrid. This trip will not be possible because I have neither the time nor the means, as I am here only to settle some family affairs, and meanwhile, my commitments in Paris are suffering from a certain delay. So, if you could come for a few days, you could bring the finished part ready for performance. If there is no way, I don’t know when or how we will meet again. I certainly won’t leave Paris, but if you go to America, the situation, as you know, does not bode well. I know that Rodrigo’s Concerto was played by a certain Yepes, I believe. As I told you, I started a transcription for harpsichord, and the part will not be available until next fall. […]”. After this letter, the possibility of performing the concerto faded away, and it was reworked only seven years later by Narciso Yepes, who played it in 1961 with the London Symphony Orchestra. The second movement worked with Carlevaro became a Sarabanda for harpsichord and orchestra. However, the reasons for this bitter ending are not known. According to Alfredo Escande’s assumption, Carlevaro felt somewhat sidelined after contributing to such a large work; perhaps he expected more help from Ohana, leading to funding from Radio France and a return to Paris, even just for that performance. What would have been a journey of a few months became a stay of over 23 years in his homeland, during which the guitarist had the opportunity to work on educational material and compositions that made him known in the world of the six strings. When Carlevaro returned to Paris in 1974, a great deal of work awaited him due to the promotion of his methods and music. Despite numerous commitments, he did not hesitate to reach his composer friend, who had continued to live in Paris in the same apartment where they had left off more than twenty years earlier. In the interview published in 1999 by Guit Art, Carlevaro recounted their meeting with precision: “When I returned to Paris in 1974, I met Maurice Ohana again. I brought the guitar with me since he expressed strong disappointment with the possibilities of the instrument because, according to him, it could not compete with the piano in terms of sound production. To demonstrate this, he positioned both forearms in a straight line, joined his hands, and pressed all the keys between one elbow and the other, producing a very beautiful sound. I told him: -Mauricio, this is the piano. Now listen to what the guitar can offer you: it’s not just six strings. Ohana replied to me, after listening to some of my improvisations: -Abel, I really like it. Wait, let me take a sheet of paper, and we’ll write something. So, working with the sounds I produced, we began to work with so much enthusiasm that when we finished, the whole night had already passed. I had to travel the next day, so he gave me the sheet, asking me to fill in the part to complete the piece. I promised him I would. After a long year, I finished the job and played Estelas for the first time in the concerts I gave during the period when I taught in the courses organized by Radio France and Roberto Vidal in Paris.“

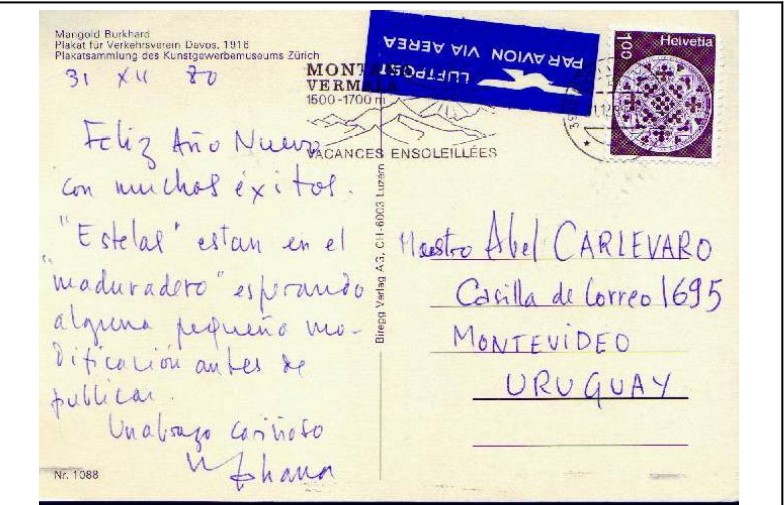

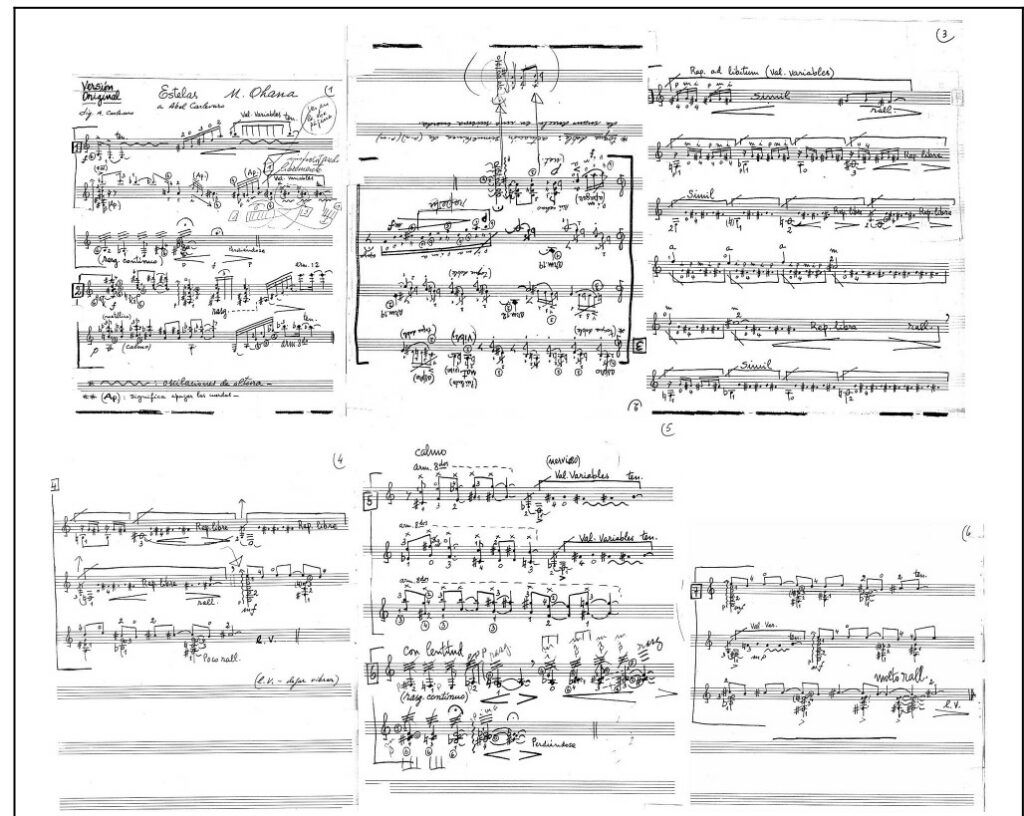

Thus, Estelas was born, which, according to the archives – contrary to what Carlevaro said – was first played in New York on March 16, 1977, and later performed in France, Colombia, and Uruguay. The performance received great acclaim from critics; on October 10, Ohana wrote: “Dear friend Abel, I am delighted to receive your news! Just these days, I wondered what had become of Estelas. I see that it was a triumph and will continue to be in your hands. I would appreciate it if you could send me a copy because I don’t even remember what the part looks like […]”. After the further success of the piece, the composer tried to insist, writing two letters dated November 21, ’78, and March 21, ’80: “[…] I would appreciate it if you could send me a photocopy of the piece as soon as possible for publication here and deposit a number of copies with the Berry publishing house […]”,”[…] I still have no news of the part of Estelas for the guitar, which you promised to send a year and a half ago. Considering that I have received nothing, I would like you to make a photocopy for me and send it as soon as possible because the catalog of my works is being published, and no music corresponds to this title […]”. Ohana received a response only on June 30 of the following year when Carlevaro wrote that he would personally visit him in Paris during his expected return on July 21. From that moment, it is difficult to understand what prompted Ohana not to want to publish the piece anymore. According to Escande’s studies, Carlevaro performed the piece 43 times in 13 different countries between March 1977 and September 2000. There are also three recordings: one from July ’79 in Porto Alegre, a second for Spanish television in ’89, and a last one in Erlbach, Germany, in ’97. We have a document dated December 31, 1980, where Ohana leaves what will be the last update on the piece: “Happy New Year, with many beautiful things. Estelas is in “maturation,” waiting for some small modifications before being published. Warm regards. M.Ohana.“

In the interviews of the following years, Ohana publicly rejected his admiration for the traditional guitar; answering Pascal Bolbach’s questions in 1982, he said: “Very soon I felt disgusted in the limited cage of the six strings […]”. In this same interview, he left a significant clue: “[…] I have just written a new suite, Cadran Lunaire, which will be published by Billaudot, commissioned by Luis Martín Diego, it is the first work for guitar in almost twenty years.” One wonders why there was such a detachment to reject the publication and almost the existence of the work itself after expressing great interest in the previous years. It is challenging to provide a clear answer to the question, although through the analysis of manuscripts and subsequent revisions, it is possible to find points that could mark a turning point on the issue. During a moment of reflection and listening together with colleague Ruben Seroussi, Alfredo Escande noticed similarities between Estelas and Cadran Lunaire. Comparing the two manuscripts and later the piece for the ten-string guitar, it is easy to observe moments of absolute analogy, suggesting that Ohana may have reevaluated the work by avoiding the traditional instrument.

Not only that, but it is clear that the composer adapted several revisions from Carlevaro. According to those who have developed this idea, when in the postcard of December 31, 1980, Maurice Ohana wrote that the piece was waiting for “some small modifications before being published,” he referred to a revision that then, over time, became a separate work capable of better enhancing his idea thanks to the ten-string guitar.

Years later, the reasons behind all these choices, sudden changes, and lost manuscripts are still not well understood. It is not even known if Abel Carlevaro really knew that Ohana was using Estelas’ material for Cadran Lunaire, whether the cadenzas of the Concerto were the result of Yepes’ work, or if Ohana used the manuscripts from 1950. It might be too risky to draw hasty conclusions, but it would be a bad choice to let the years go by without finding material that opens up a new interpretative perspective. Despite the still-open questions, it is essential to continue telling the story of such a long and prolific friendship, which has managed to color the 20th century with its art, the traces of which it would be unfair to lose.

Special thanks to Alfredo Escande, Corinne Monceau, Dominique Souse, and the association Les amis de Maurice Ohana for kindly providing information and images for this article.

Originally published on Guitart n. 101