“The guitar has always fascinated me, not only because of its timbre but because I consider it a mysterious instrument, from which emanates a mystery that can be communicated to very few people.”1

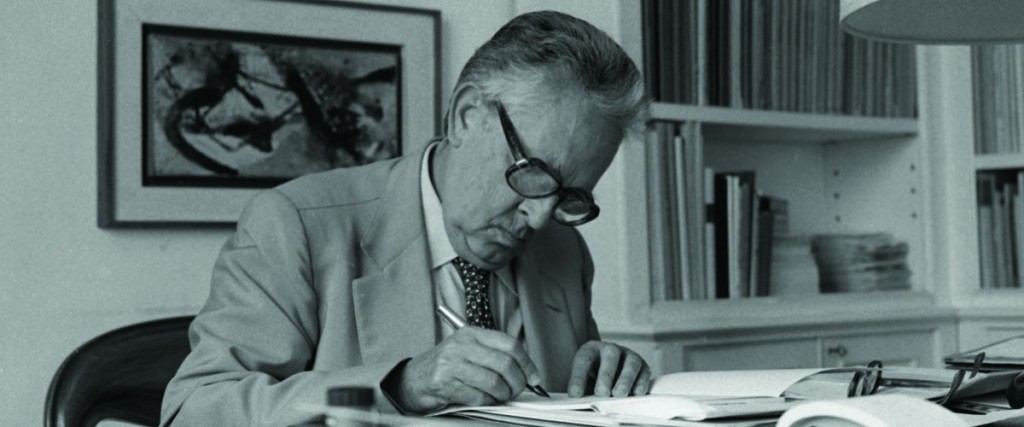

Goffredo Petrassi was one of the most prominent Italian composers of the twentieth century. Known and admired worldwide, he gifted the guitar with some iconic pieces of the twentieth century: Nunc and Suoni Notturni. However, his output for the guitar is not limited to solo works; it also includes chamber music compositions of great significance.

Goffredo Petrassi, born in 1904, was a native of Zagarolo but soon moved to Rome, where he attended the Schola Cantorum of the Church of San Salvatore in Lauro. His passion for music led him to study composition and organ at the Conservatorio Santa Cecilia, where he graduated in 1932 and 1933, respectively.

Petrassi’s catalog boasts more than ninety compositions, including orchestral music (notably the series of Eight Concertos for Orchestra), choral music, chamber music, solo instrumental music, operas, ballets, and even film music.

To fully understand his music for the guitar, it is essential to trace the key milestones of his career. The first composition that brought him international recognition was the Partita for Orchestra, composed during the summer of 1932 by the young Petrassi. Alfredo Casella conducted it in Amsterdam in 1934, at the XI Festival of the International Society for Contemporary Music. The form of this composition is deeply rooted in ancient music, and the revival of musical traditions marked the first part of Petrassi’s output.

The four pieces that Petrassi composed for the guitar belong to a later period in his career, during which he gradually distanced himself from neoclassicism to pursue a path entirely his own. In this experimental phase, chamber music plays an essential role, allowing the composer to focus on individual instruments.

“The transition from a before to an after”, as Petrassi himself states, is marked by the First Serenade (1958) for five instruments, where the guitar, however, is not yet included.

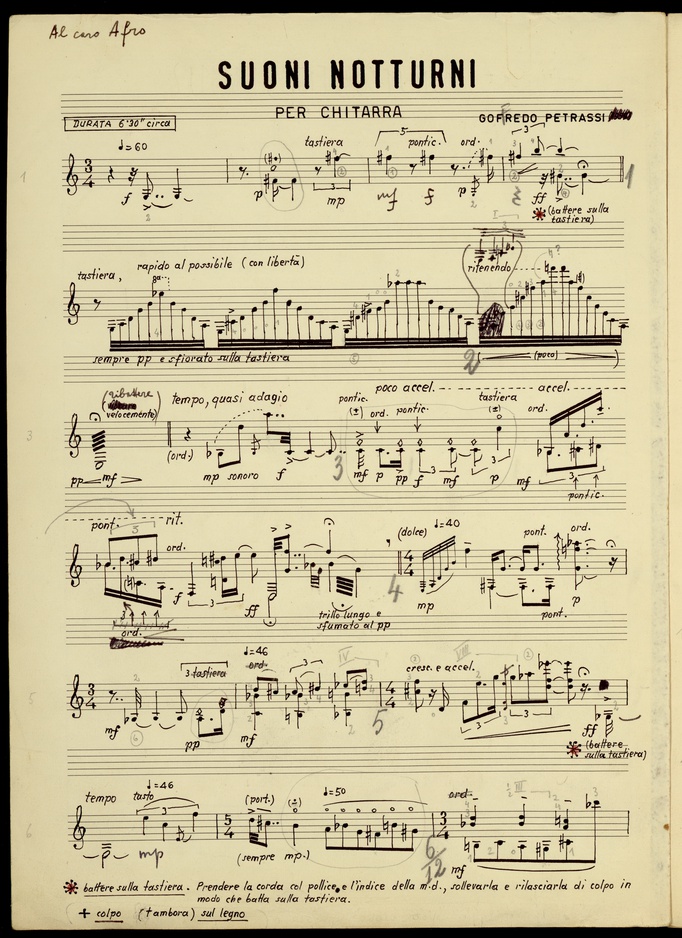

Suoni Notturni, composed in 1959, is Petrassi’s first piece for solo guitar. It is dedicated “to dear Afro,” referring to Afro Libio Basaldella, an Italian painter from the post-war period and one of the leading figures of abstract art, who also worked as a scenographer for some of Petrassi’s operas. It is important to note that Petrassi was an avid art collector, along with his wife Rosetta Acerbi, and that the close relationship between music and visual arts was one of the composer’s key interests. Petrassi was an intellectual deeply engaged with art in all its forms.

The piece in question is Petrassi’s response to a painting dedicated to him by Afro Libio Basaldella, titled Notturno, which naturally inspired the composer to create Suoni Notturni. The opportunity to compose a work for guitar came from Ricordi Publishing, which proposed the idea of publishing a volume of contemporary music. This led to the well-known Antologia per chitarra (1961), where besides Suoni Notturni, pieces by Auric, Guarnieri, Ghedini, Malipiero, Poulenc, Rodrigo, Sauguet, and Surinach are also featured.

Critic Mario Bortolotto described the piece as “a reconsideration of the classical study (Tarrega or Sor),”2 where the techniques used become the driving force of the composition. However, the piece presents an autonomous form, in which timbres and agogics are predominant:

To write the first piece for guitar, I had to engage with it, though not to the point of playing it myself, as I lacked the patience to study it. Instead, I focused on examining the music written for guitar: what had been written, and more importantly, not so much technically but timbrally.3

Timbre thus becomes a crucial aspect of the conception of the instrument, as will be evidenced by subsequent works.

The juxtaposition of different timbres is further explored in the Second Serenade-Trio, which features three plucked string instruments: harp, guitar, and mandolin. This choice of instrumentation would later be echoed in the piece Carillon, Récitatif, Masque from 1974 by Hans Werner Henze, another 20th-century composer closely associated with the guitar.

Once again, Petrassi demonstrates his avant-garde approach both in his musical material, which approaches a sort of abstraction in music, and in his choice of instrumentation. These three instruments interact following their idiomatic technical specifications while also exploring new timbres. However, as critic Massimo Mila notes, “Petrassi’s instrumental imagination does not exhaust itself in timbral dimensions… but sustains the invention of musical vocabulary, indeed, of concrete musical figures.”4

It is no longer possible to speak of true themes, recognizable melodies, or rhythms that provide unity to the piece: these new “figures” do not adhere to the musical rules familiar to listeners but create new paradigms.

Almost ten years after the experience of the Second Serenade-Trio, Petrassi returned to the guitar. It was in 1971 that he composed his second and final piece for solo guitar, titled Nunc. Dedicated to his life partner, Rosetta Acerbi, it was first performed by Mario Gangi at the Venice Contemporary Music Festival. The same instrumental techniques from the first piece, Suoni Notturni, are used, but as Petrassi himself notes, the novelty lies in the use of percussion. Two types are identified: one is the tambora on the soundboard, and the other is the so-called “Bartók pizzicato.”

To understand better Petrassi’s relationship with the guitar, it is interesting to read the composer’s own words in the interview by Ruggero Chiesa, published in 1972 in the magazine Il Fronimo.5

Petrassi confessed that the guitar had always fascinated him and recounted having studied how to compose for the guitar by reading Hector Berlioz’s Grand Traité d’Instrumentation. He never learned to play it himself, but sought assistance from Maestro Mario Gangi, whom he consulted for advice on the two solo pieces. Petrassi acknowledged the difficulty of composing for the guitar and encouraged performers to explore new timbral possibilities to expand the palette of sounds.

“It is difficult for the composer to go beyond certain combinations, while this can happen on the part of the performer, who can discover different things.”6

Among the virtues that the composer recognizes in the instrument is its intimacy, and he compares playing the classical guitar to “conversing with a person.” The delicate volume is thus an added value for Petrassi, who does not appreciate the timbre of the electric guitar, which he describes as “detestable.”

Intimacy and timbre are further complemented by mystery, which, according to the composer, is one of the most interesting aspects of the instrument. These three elements, combined, give the guitar its unique allure.

In 1977, Goffredo Petrassi’s exploration of the guitar came to an end. Chamber music played a central role in defining Petrassi’s style, and his journey with the instrument concluded with a work for ensemble.

Alias, for guitar and harpsichord, follows the same timbral logic as his earlier Seconda Serenata-Trio. In this piece, two instruments with very different histories are contrasted and brought into dialogue, united by their plucked strings. The title aptly reflects the concept behind the composition: “alias,” from Latin, means “otherwise,” “in other words,” or “that is to say.”

Examining Petrassi’s correspondence, partly preserved at the Fondo Petrassi of the Campus Internazionale di Musica in Latina and partly at the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, offers insight into the composer’s mindset and provides a deeper understanding of his approach to chamber music. In a letter from 1978 addressed to the critic Massimo Mila, Petrassi wrote:

In November, a record is expected to be released featuring the two guitar pieces, Seconda Serenata-Trio [guitar, mandolin, harp], and a new piece recently completed, Alias for guitar and harpsichord. I have sworn to myself to stop working with these two instruments and to focus on something more serious with chamber music in general.7

Despite this testimony, Petrassi’s works continue to provoke reflection on the possibilities of our instrument and challenge today’s guitarists.

Although chamber music was a crucial turning point in his new musical conception, Petrassi admits to favoring his orchestral and choral works, considering them of greater effort and value. Nevertheless, few composers have experimented as extensively with the timbral exploration of plucked string instruments, and Petrassi stands as a significant figure in the development of chamber music with guitar.

Originally published in Guitart n. 110.

- 1. «Il Fronimo», Issue 1, October 1972 (original in Italian). ↩︎

- 2. M. Bortolotto, Il Cammino di Goffredo Petrassi, «Quaderni della Rassegna Musicale», I, Torino, 1964. (original in Italian) ↩︎

- 3. L. Lombardi, Conversazioni con Petrassi, Suvini Zerboni, Milano, 1980. (original in Italian) ↩︎

- 4. M. Mila, Goffredo Petrassi, «DEUMM», 1986, p. 671. (original in Italian) ↩︎

- 5. «Il Fronimo», numero 1, Ottobre 1972. ↩︎

- 6. Ibidem. ↩︎

- 7. Letter from Goffredo Petrassi to Massimo Mila, March 28, 1978, held at the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel. ↩︎