Ramon Lazkano (*1968) is one of the most recognized composers of his generation. His works boast collaborations with ensembles such as Ensemble Intercontemporain, Ictus, Ensemble Recherche, Quartetto Diotima, Orquesta Nacional de España, Bavarian Radio Orchestra, and the RAI National Symphony Orchestra. He has won numerous international awards, including the Fondation Prince Pierre de Monaco and the Georges Bizet Prize from the Académie des Beaux Arts. Additionally, he has been an artist-in-residence at the Real Academia de España and the Académie de France in Rome.

Describing his music is complex: his concept of sound encompasses details that touch silence, evoke poems and landscapes, yet are supported by a strong structure, a tangible sign of his remarkable artistic personality.

In this interview with Obiettivo Contemporaneo, we discuss his works for guitar, his career, and his projects.

Ramon, thank you for accepting our invitation. Your repertoire for guitar is vast, stemming from a technique that has marked a precise trajectory and defined your aesthetics in all its aspects. How did you approach the guitar?

The guitar has accompanied me since I was a child, although I have never been a guitarist. In my room, next to the piano on which I studied every day, there was one that I would strum from time to time to get to know it better. For me, it remained an instrument of somewhat impenetrable familiarity. During my years of study at the Conservatory of Paris, I got to know Didier Aschour, a great friend to whom I have dedicated several works. A little later, in the ’90s, I met Eugenio Tobalina, a guitarist who at that time focused his activities on new Basque music, and he truly introduced me to the instrument as a composer. Caroline Delume and Francisco Luque, both guitarists, became very close to me, thanks to the Colegio de España and Felix Ibarrondo. Everything took shape progressively—a sum of pieces, contacts, and details that allowed me to explore an instrument whose ergonomics have always fascinated me.

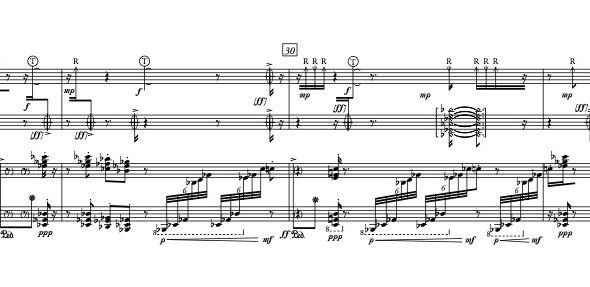

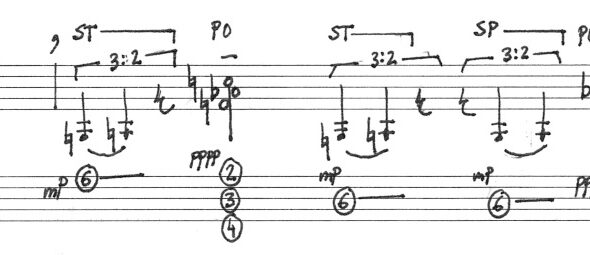

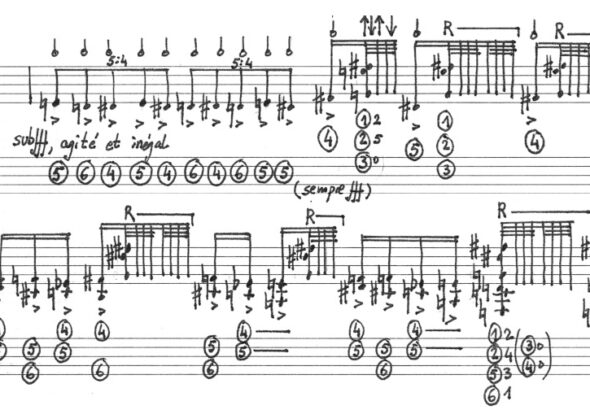

As we know, writing for the guitar is very complicated. Your music, however, does not seem to suffer from any technical difficulties: every dynamic, timbral choice, and phrase are part of a structure, of a direction. What difficulties have you encountered while writing for this instrument?

Great difficulties, I confess! I remember drawing a chart with all the indications to study the positions on the guitar, although it did not turn out to be very effective… The guitar has always evoked an idea of intimacy for me: the embrace of the musician with their instrument is evocative, the way they lower their head and the two actors share their secrets. The six strings have allowed me to explore different techniques that have had decisive effects on the music: microtonal frets, scordatura, rasgueado, percussion. In Malkoak Euri Balira (If the Tears Were Rain, based on a poem by Xabier Lete), for two voices and three choirs, behind the central choir is a hidden monitor that diffuses the sound of a guitar playing backstage: it is like an enigma, an invisible presence that emanates an unexpected sonic aura. For me, it was a way to transcend my idea of the folk song, to safeguard the voice accompanied by a guitar, in a context where poetry turns it into magic.

A new album has just been released by Odradek Records, featuring Neue Vocalsolisten, L’Instant Donné, Johanna Zimmer, and Manuel Nawri interpreting some chamber works, such as Main Surplombe (2013) for soprano and seven instruments. Additionally, the Preludios, one of your more recent works, have been published. Could you tell us a bit about these pieces?

In both, the guitar is part of the ensemble: what is your approach to writing when this instrument is part of a chamber group? Main Surplombe was commissioned by my friend, guitarist, artist, and composer Bertrand Chavarría-Aldrete. The relationship with Bertrand was fundamental in many respects, and it was from our closeness that Ezkil, for guitar with microtonal scordatura, was born. In the second piece of the diptych on some poems by Jabés, Ceux à Qui, I use the guitar, but this time manipulated by a percussionist. As for the Preludios, three guitars are needed: two classical (one of which with scordatura) and a folk guitar played with an e-bow. Briefly, for me, polyphony is an irradiation of the sound fabric relative to the initial instrumental efficacy, an extension of the conditions that give rise to the sound. Stravinsky said something similar, referring to his octet—with distinct aesthetic implications, of course—when he explained that forms of polyphony appear based on the specific qualities of the instruments.

Of Basque origin, you have lived in Paris for many years. You have been musically trained thanks to choral music, studied piano and composition. How did your artistic career develop? What led you to write?

In my case, writing and piano were not activities that developed at different times but simultaneously. I have been singing since I was young, participating in the school choir and later the high school choir, alongside my first contact with the piano (an old black, heavy upright Pleyel with discolored ivory keys) at my grandmother’s house, thanks to whom I approached the instrument and improvisation. I remember my first experiments with writing were around 7 or 8 years old, and by 12 or 13, I had already written small pieces for piano that I played in some school recitals. Nothing specific led me to compose; I don’t come from a family of professional musicians except perhaps my aunt, who was an organist and introduced me, around the age of 14, to the man who became my teacher in San Sebastián, the composer Francisco Escudero, a great person who gave me indelible lessons. I have never put aside musical practice: the piano continues to be the central actor in my existence as a musician. I have directed, programmed, produced, and taught: I think all this allows me to live in accordance with what music represents for me.

These pandemic years have transformed the world of culture, accentuating all the difficulties that the sector was already facing. Spain and the Basque Country continue to suffer from all this: how do you see the cultural situation in your country? Do you think there could be a change after two such difficult years?

My country is not a territory; my country is a community of affections, a living context that welcomes me, each with its familiar languages that allow me to say the same thing, but in different ways. My country is made up of people who dream, invent, and think about the world with the fragile temporality that dazzles them. These days, I read a beautiful poem by Jose Antonio Artze in Euskera, “Gure bazterrak,” which says: “I love our corners when the fog hides them and prevents me from seeing what it conceals because from then on, I begin to see the hidden part, the wonderful corners that illuminate my inner self.”

The “Cultural Situation” (is it an oxymoron?) is a fog, a pretext for not seeing inexorable changes, a reproach from above: the problem is not the cultural situation, but the economic and social model that turns us into slaves of a mitigated and gagged thinking. This is global, not specific to a territory.

Your artistic career is not only tied to composition: for several years you have been working as a professor at the Centro Superior de Música del País Vasco Musikene. How do you structure your lessons? How do you view the new generation of composers?

I have fluctuating ideas about how to offer education to young people, especially in a field like ours, which is technical, artisanal, and methodical but must shed these initial acquisitions to find the conditions that give rise to a keen imagination and free fantasy. I suppose that my way of teaching tends to establish an exchange that takes into account the specific personality of each student. However, I imagine that moments of teaching that no longer belong to our era will appear in my way of sharing my experience and practice, because the entire transmission context has been radically modified with new technologies and various levels of understanding.

Young composers assume a legacy to transform it into a metamorphosis directly linked to the world they have encountered, their living conditions, ecological and sociological crises, the erosion of ideologies, and the disbelief in parliamentary politics. All this seems to me to reflect an essential alteration of the values that, in my generation, we naively thought would never change. Visual contact, the speed of information, the thought of socio-artistic activity as a value superior to the immanent object, are aspects of an ongoing revolution. From my perspective, forms of listening, time, and sound architecture seem to be in extinction, but for young people, they are jungles to explore and oases for their thirst.

Do you have any future projects where the guitar takes center stage?

At the moment, no: I am working on a piano concerto that will have its world premiere by Alexandre Tharaud and the Orchestre National de France with François-Xavier Roth next February. However, I do not at all rule out the possibility of continuing to use the six strings in other compositions or even dedicating a solo role to the guitar, an idea that has been evoked several times and unfortunately postponed until now.

Originally published on Guitart n. 107