Today’s chat dives into Maurizio Azzan’s guitar music, an up-and-coming figure among young composers in the avant-garde scene. After earning a degree in Classical Literature, Maurizio dove headfirst into composition, studying with A. Solbiati in Milan, F. Durieux and Y. Maresz at CNSM and IRCAM in Paris, and refining his craft with Salvatore Sciarrino. His music has graced the stages of renowned festivals worldwide, including the Biennale Musica in Venice, ManiFeste, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, Wien Modern, Milano Musica, Teatro la Fenice in Venice, Impuls Graz, and MITO SettembreMusica. Aside from delving into his guitar work, we’ll seize the opportunity to chat about Maurizio’s experiences, the encounters that have shaped his career, his teaching activities, and what’s on the horizon for him.

Maurizio, thanks for being here with us.

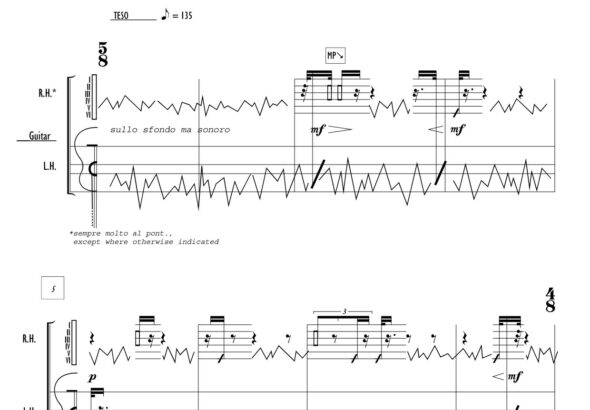

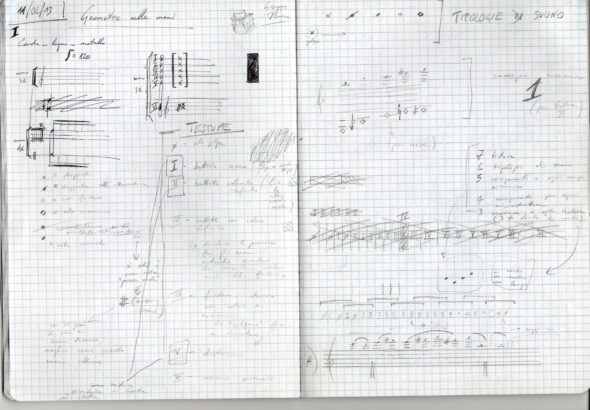

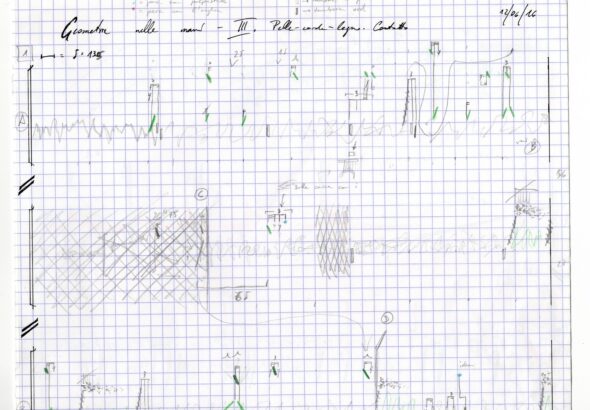

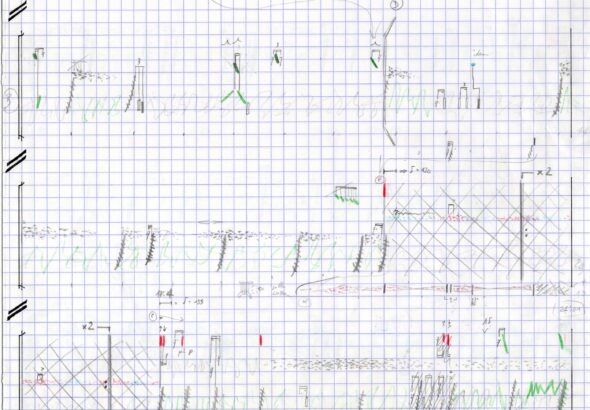

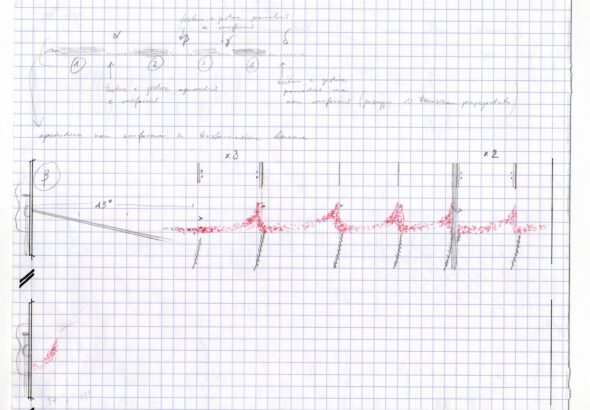

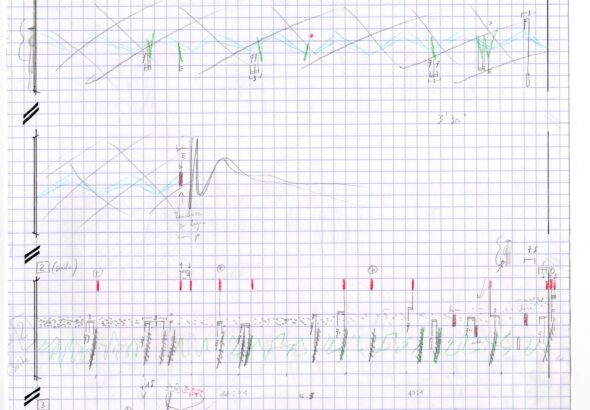

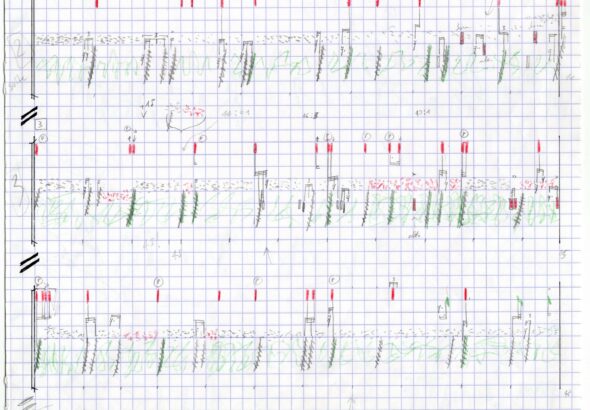

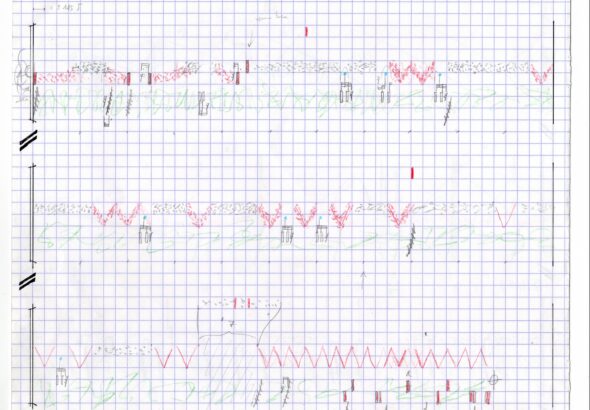

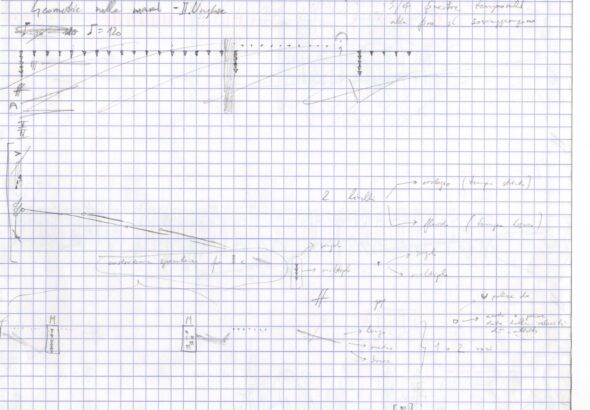

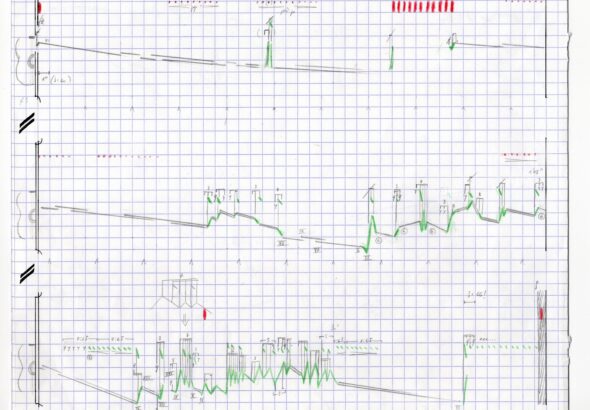

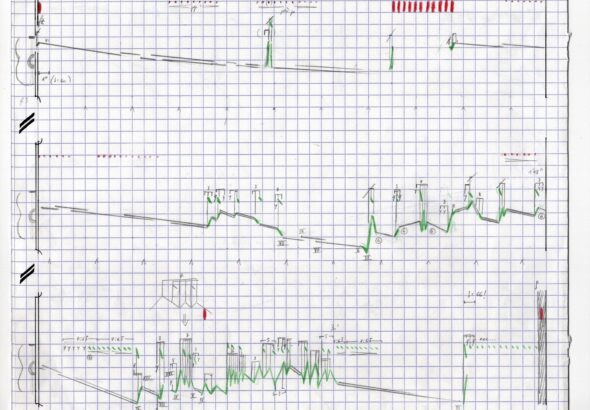

Let’s dive into your music. Your first solo guitar piece in your catalog is “Geometrie nelle mani,” a work in three movements written between 2013 and 2016. It seems to aim at highlighting various details of the instrument and the hands of the performer: from the wood to the strings, from percussion to the sound produced by nails and skin. The result feels almost like a “guided” listening experience, leading the audience to discover an unexplored aspect of the guitar. How did the idea for this piece come about?

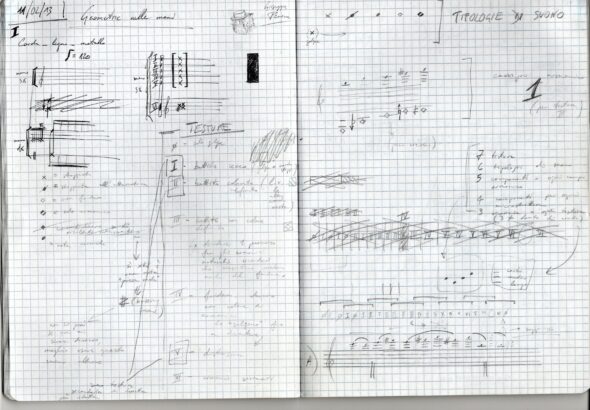

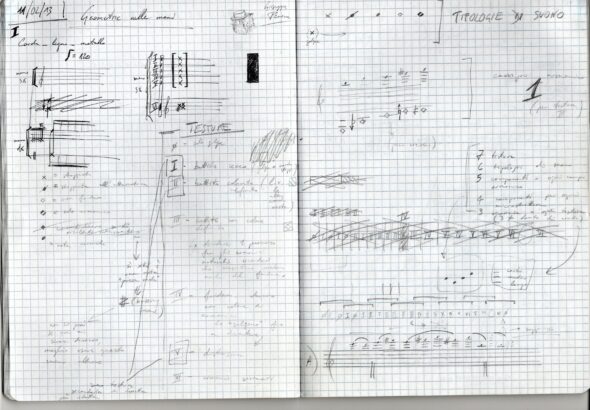

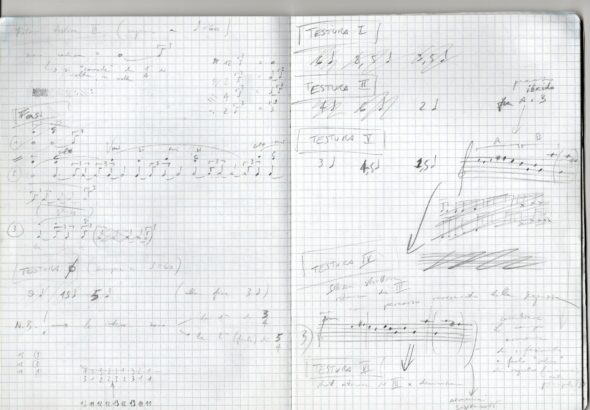

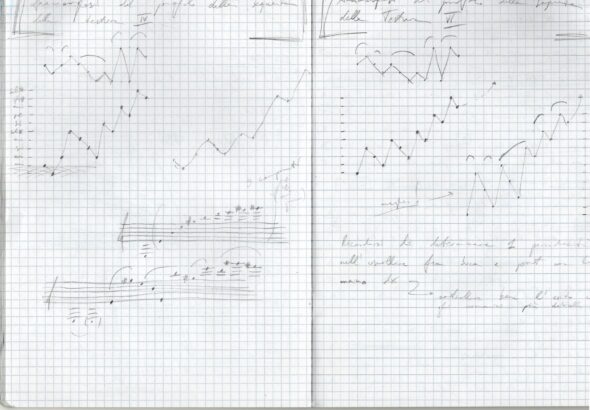

Despite the initially striking aspect of this work being its unconventional sound, what drove me to write it was actually the need to create a space for reflection to seek small-scale solutions to some compositional problems I encountered along my journey. “Geometrie nelle mani” started as a sort of personal laboratory where I delved into certain formal and expressive intuitions in preparation for subsequent works. From this perspective, I could almost say it was more about compositional studies rather than technical-executive ones. However, since, by complete coincidence, these study phases of mine always coincided with guitar-related works, I decided to return once again to the instrument for which I had already written quite a bit as a student. I took advantage of this opportunity to put down on paper certain aspects of its sound that I hadn’t truly focused on until then and that seemed to me not to have been adequately explored in the existing repertoire.

Exploring the guitar through improvisation, one easily realizes how its surface made of strings, wood, and metal can be likened to a complex territory inhabited by interrelated sounds. For me, composing means searching for these relationships to understand them and choose which ones to highlight, thus allowing the sound to acquire meaning and expression.

What vibrations do the various points of the instrument generate? Through which movements? What historical heritage do they carry, and which contexts are able to highlight or conceal it? At the heart of it all is the need not to take anything for granted and to reposition what we are willing to accept as traditional within a broader framework, in order to better understand the nature of the sound body in front of us. Of course, in this reordering of ideas, there is no intention of desecration or rejection of the already known; it’s simply a way to create the necessary conditions for a conscious choice of a research context.

The photographic and sculptural cycles of Giuseppe Penone that give the title to this collection of guitar studies, which I had seen shortly before starting to write the first study [in February 2013], place at the center of everything the investigation of the contact between the object and the hand that grips it. This giving substance to what apparently has no volume led me to search for something similar in the relationship between hands and instrument: what sound does the space between the performer’s gesture and what we are accustomed to accept as traditional have? And if I observed this space from within or from afar?

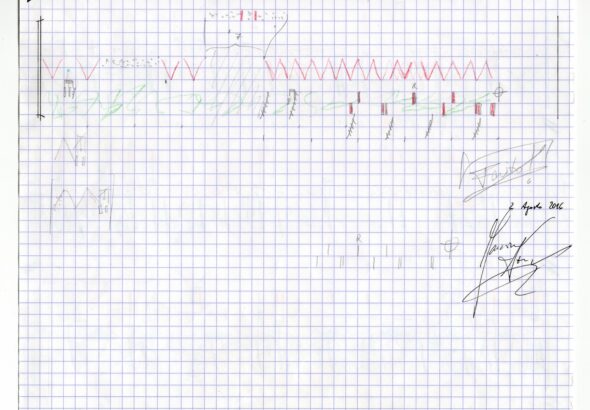

After writing the first study, however, I set aside the continuation and dedicated myself to other things for almost six years. In reality, I wasn’t brave enough to continue because I feared I had pushed too far with the technical demands on the performer. The entirely chance encounter in Paris with Ruben Mattia Santorsa, to whom “Geometrie nelle mani” is dedicated, and his beautiful performance of the first study created the conditions for me to take up the project again and complete it with the other two pieces, which he then presented at the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt in August 2016.

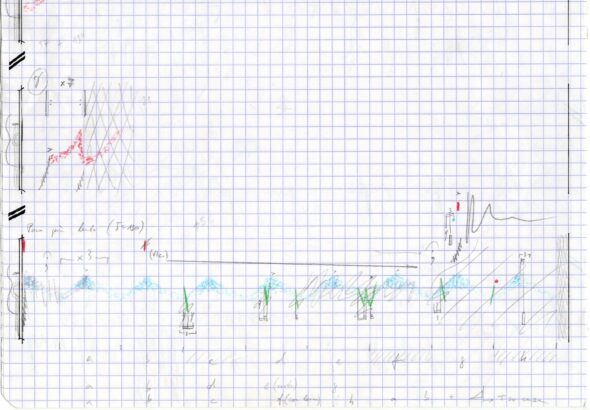

Five years later, American guitarist Jordan Dodson performs “Instabile. Propagandosi,” a commission from the MATA Festival in New York that gave birth to “Geometrie nelle mani II,” a new collection of studies still in the gestation phase. How has your approach to the instrument changed after such a long period of time?

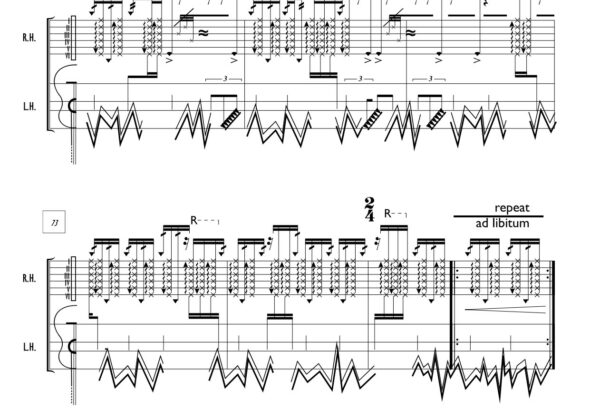

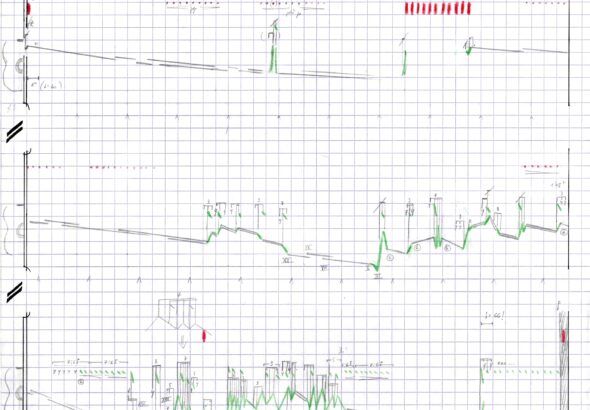

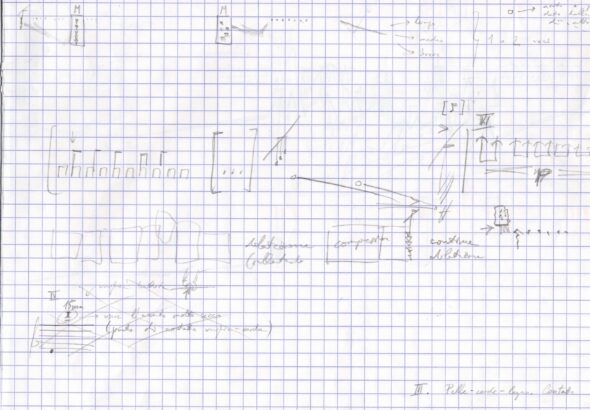

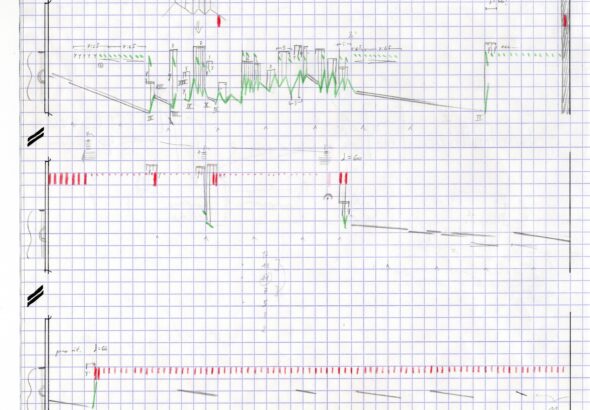

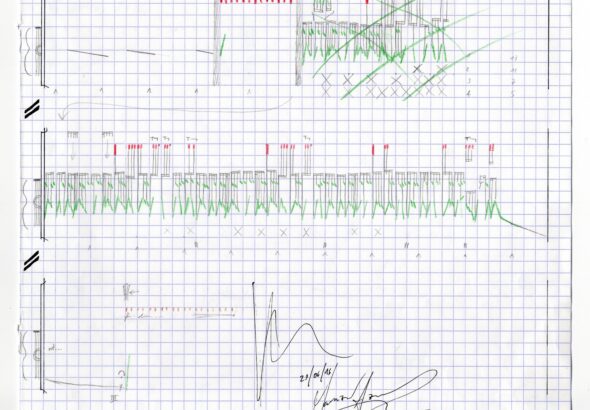

More than the approach to the instrument itself, I would say it’s the perspective from which I observe my musical material that has changed. If you compare the scores of the third study of “Geometrie nelle mani” and “Instabile. Propagandosi,” for example, you can easily see how, despite very similar performance techniques, the form has become much more articulated and fluid.

Previously, my main focus was on investigating the materiality of sound itself, but in recent years, it has been primarily the formal exploration around unstable time and space that has captured my attention. How can I make it perceptible that the exploration I am conducting has a point of view that varies in parallel with the changing explored territory? By constantly shifting between macroscopic and microscopic dimensions and vice versa, sound is projected into different spaces and temporalities, leading to the discovery of new aspects of sound or affinities between seemingly contrasting elements. If, for Gérard Grisey, time essentially had only three dimensions – the dilated time of whales, the normal human time, and the accelerated time of insects – now we realize that these are just specific points in a nonlinear, continuous, and infinite research space.

In general, each piece in “Geometrie nelle mani II,” of which “Instabile. Propagandosi” will be the last, is conceived as another exploration of some aspects already present in the corresponding study of the first collection, somewhat like revisiting the same city after years of absence. To draw a comparison with Penone’s works that inspired the writing of these pieces, my second collection of studies is to the first as his homonymous sculptural cycle is to his photographic one.

In addition to solo repertoire, your interest in the six strings is already evident in two of your early works: “Amma” for two guitars from 2011 and “Finding a Tendency,” a piece for ensemble from 2012. As we know, the guitar is a challenging instrument to integrate into an ensemble, considering the difficulties with sound volume. How do you approach this challenge, and how do you manage to create space for the guitar in a chamber context?

I believe that sound volume is merely a contextual issue. Before Claude Debussy composed “Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune,” it was widely assumed that the low register of the flute was almost unusable in an orchestral setting. Yet, once it found an appropriate context, suddenly its potential, previously untapped, became evident.

The real problem never lies within the instrument itself but rather in the ability of those who use it to exploit its characteristics. Viewing the guitar as a watered-down counterpart of a keyboard instrument is a misconception that irreversibly compromises the outcome of the work. However, when one finds a context in which the guitar sound shines, there is no impression of imbalance, as demonstrated by successful works like Simon Steen-Andersen’s “AMID” or Julien Malaussena’s “Exigüe(Contigüe).”

In general, in my works, as in much other contemporary music, there is a clear recourse to what the French spectralists call instrumental synthesis. The parts are conceived as interdependent components of sound rather than counterpointed lines. This approach allows for great articulation flexibility, ranging from total fusion to moments where specific instruments stand out from the mass. Regarding this, it’s no coincidence that the first of the works you mentioned, “Amma,” has that title: άμμα, in ancient Greek, means knot or even a grip between two wrestlers, and indeed, it was the first piece where I consciously sought to maintain an approach of total fusion between the sonic sources.

However, this dialectic between fusion and emergence can only be mastered by empirically verifying the overlap of various instrumental timbres to detect any spectral masking phenomena that may obscure components of the sound that we want to highlight or give excessive prominence to secondary details. While now I use software for sound editing to construct partial simulations of the most complex areas of my works, when I wrote “Amma” and “Finding a Tendency,” I didn’t have access to these resources. There, it was constant work with the performers—Andrea Monarda and Michele Ambrosi in the first case, and the New Ensemble in Amsterdam in the second—that allowed me to gradually verify the effectiveness of what I was writing.

During your academic studies in Turin, Milan, and Paris, you had the opportunity to live experiences and meet musicians who would become crucial for your artistic development. Which ones are the most significant?

Certainly, I owe a lot to several teachers I had the good fortune to encounter during my academic journey, such as Giorgio Colombo Taccani at the Turin Conservatory, Alessandro Solbiati at the Milan Conservatory, and Frédéric Durieux and Yan Maresz at the Paris Conservatoire. Now that I am teaching myself, I realize how each of them left something important with me, even when our perspectives seemed at odds.

Besides them, I had some encounters with composers who struck me through their musical expression, helping me understand the kind of composer I wanted to be. Among them, my meeting with Salvatore Sciarrino was undoubtedly the most significant. I followed his annual course, which deeply influenced me. His way of living art in every form taught me to look at the world with curiosity, openness, and a desire to investigate the underlying connections that link diverse artistic experiences and the past with the present.

During my time as a student at IRCAM in Paris, I had the opportunity to meet Thierry De Mey, who was then a composer associated with the Cursus program—a well-rounded artist with disarming humility, capable of ranging from music composition to choreography, from video directing to performance. I think it’s only thanks to his encouragement that I dared to embark on paths that I might never have dared to pursue without meeting him.

The period between 2012 and 2016 coincided with constant interaction with some composer friends with whom I shared a lot, such as Giulia Lorusso, Lorenzo Troiani, Zeno Baldi, Julien Malaussena, Michelle Agnes, Lorenzo Restagno, Emanuele Palumbo, and many others. Giulia, Emanuele, myself, and the musicologist Giulia Accornero were part of a small association in Milan that organized concerts and masterclasses for composers. In that context, we managed to invite personalities whose lessons definitely influenced my journey, such as Franck Bedrossian, Dmitri Kourliandsky, Helmut Lachenmann, Giorgio Netti, and Simon Steen-Andersen.

However, two other figures were crucial in my development: Pierluigi Billone and Francesco Filidei. I met Billone on several occasions over the years, and each time coincided with a significant step forward for me. I remember once, with extreme generosity, he gave me a three-hour lesson at a friend’s house. Three hours to try to investigate together, through the analysis of a passage in one of my pieces, what I was really seeking in music—it was perhaps one of the most powerful moments I recall from my educational journey. I met Filidei during a course, and we continued to keep in touch over time. I believe that no one pushed me more than him to fully commit to what I was doing without unnecessary compromises. Just before starting the first study of “Geometrie nelle mani,” for example, I met him in Milan before a concert. He told me that I needed to push harder to bring out myself, even if it meant writing a piece using the table in front of me as an instrument, if necessary. At that moment, I returned home with many thoughts, but then the situation began to unlock: the guitar became my table.

For several years, as mentioned in one of the answers, you’ve been alternating between your career as a composer and that of a teacher. How do you organize a suitable study path for your students? How do you plan your lessons?

Teaching has been a part of my journey since I was a student. It’s something I could never give up because it allows me to better understand my own music-making by observing things from perspectives that would otherwise escape me. For me, teaching composition means engaging in a dialogue on an equal footing with my students to help them develop problem-solving skills and self-analysis that eliminate the layers of clichés stifling each person’s unique personality. As I often say, the self that listens, interprets, and composes shares underlying connections: my task is to help students articulate them to find the deep roots of their musical personality.

To achieve this goal, with less experienced students, I initially focus solely on improvisation and listening. I believe that even from a clumsy result and the ensuing discussion, we can learn a lot about the cultural background and nascent peculiarities of the individual in front of us. Once areas of interest are identified, we then move on to technical discussions about formalization and writing without the risk of pushing the other person toward pre-packaged solutions that may not align with their expressive needs. With more advanced students, we work more on aesthetic awareness, although at times, I find it necessary to do significant work upfront to recover the deeper reasons for composing because the competitive climate of the contemporary music world often leads to a bulimic and uncritical practice far from the deeper sense of art-making.

In addition to the more compositional aspects, I believe that studying historical writing practices and engaging in constant analysis are indispensable at every level. Actively engaging with repertoire, rather than academic memorization, is how we learn to understand its language and aesthetics. Comparing oneself with others, whether recent or ancient, allows us to see firsthand the answers that have already been given to the questions we ask ourselves. To broaden the horizons of students, I also insist that they attend masterclasses and seminars by other composers and musicians and connect with peers. It’s crucial for a young composer to feel part of a community and have free spaces for discussion outside of the classroom.

Overall, I always hope that the educational experience is extremely personal and not standardized for each individual. I recall how a few years ago, during one of his lectures, Kourliandsky said that teaching everyone the same things in the same way would be like feeding a mouse, a dog, and an elephant the same food in equal amounts: someone might die, and there are no guarantees for anyone’s survival. I believe he was absolutely right.

Would you like to reveal some of your future projects?

The most demanding project awaiting me at the moment is a commission from the Impuls Festival in Graz for the Klangforum Wien, which will be presented in February 2023. Before then, in addition to the ongoing project of Geometrie nelle mani II, I have in the pipeline a work for accordion and electronics for Carlo Sampaolesi and one for Jean-Étienne Sotty for augmented accordion, a recently developed instrument at IRCAM in Paris capable of diffusing electronic sound from within without the use of additional speakers. In the drawer, there’s also the new version for electric guitar of Geometrie nelle mani, which Ruben Mattia Santorsa and I started working on during the last lockdown, and a new piece for electric guitar and electronics for Carlo Siega. Fingers crossed, I hope that with the new 2021/22 season, we can return to making music in person steadily without excessive limitations. It’s much needed.

Originally published on Guitart n. 104