Alberto Carretero (*1985) is a versatile Sevillian composer with a keen interest in various aspects of contemporary music and beyond. As a teacher of electroacoustic composition at the “Manuel Castillo” Higher Conservatory of Music in Seville, he has garnered numerous accolades, including the Caja Madrid Prize – “Andaluces del Futuro,” the Contemporary Music Composition Prize “Injuve,” the “Real Maestranza” Prize, the second Prize for Orchestral Composition “Antón García Abril” (Madrid), the “Jóvenes Compositores” Prize awarded by Plural Ensemble, the “Ciudad de Sevilla” Prize, and the Sevilla Joven Prize from the Consejería de la Presidencia de la Junta de Andalucía.

With a musical language consistently oriented towards mimesis and historical contamination, Alberto Carretero often draws inspiration from archaism to rework material in an extremely personal and innovative manner.

Alberto, thank you for accepting our invitation. Your educational background is quite eclectic: music, engineering, journalism. How do these diverse paths come together, and what led you to choose composition?

First of all, I thank you for this initiative to engage with current guitar composers and for your efforts in promoting contemporary creation.

Due to my immense curiosity about various fields of knowledge, my education is multifaceted. Music, always at the core, connects me to interests in science, technology, arts, and the humanities. In reality, I believe all these areas converge more than one might think: they are different perspectives on the human experience and continuously nourish each other. Through musical composition, I seek to bring them all together from my personal standpoint, synthesizing new knowledge and forms of expression, drawing from various creative stimuli.

Compared to the beginning of your career as a composer, you approached the guitar only in 2015. Your first prize-winning piece, “Oud,” features a guitar with a noticeable scordatura, which, as the title suggests, alludes to a deep connection with Arab culture. Could you tell us more about it?

During my time as a conservatory student, I wrote other pieces that incorporated the guitar, but the first work in which I delved deeply into the instrument was “Oud,” thanks to the collaboration with Pedro Rojas-Ogáyar, a member of Ocnos, who recorded it on his CD “Excepciones,” released by the record label “La Mà de Guido.”

As in other subsequent projects where I composed for the guitar, I try to “reimagine” the instrument, thinking about “hybridizations” with other instruments in its family, both from other cultures and ancient ones. In this case, the Arab musical and cultural heritage inspired the creation of this new piece. From an organological perspective, I was interested in reflecting on the sound of the oud, an Arabic lute found in various Mediterranean and Eastern traditions. I sought a guitar sound imbued with Andalusian music, not aiming for a strict imitation but rather an evocation in the form of an “imaginary oud” or even an “imaginary guitar” that often steers the typical color of the instrument towards other timbres and textures.

The conception of the lines closely resembles those of the human voice, with its melismas and articulations. Additionally, I altered the usual tuning of the instrument through a scordatura, lowering the lowest string to “C,” to get closer to the sound of the oud and explore both the lower register and the harmonic resonances of the fifths. Another key element of my work was ornamentation and the creation of musical dramaturgy based on the interplay of these ornaments, leading to metamorphoses or hybridizations of the material itself when the main lines coincide in different directions with different intensities. This allowed me to create an almost concentric flow of music that maintains its energy through this opposition.

The work is written with the indication of “Tempo rubato,” conveying the idea of an interpretative approach resembling improvised music in terms of rhythmic and temporal looseness. The first sounds heard are multifonics, obtained as “false harmonics” placed in unconventional positions on the guitar strings, producing various simultaneous sounds and a very characteristic timbre, akin to that of a bell in terms of fundamental pitch indeterminacy. This initial material of the piece has a static character, somewhat “testing” the instrument, subtly changing color and rhythmic pace.

From some notes emerging in these multifonics, a second dynamic material is introduced, tremolo and changing pitch through the use of glissando. These first two materials gradually begin their interaction and mutation towards microtonal and Eastern sounds that retain the characteristics of the initial ones but start to bend and transform through the use of a slide.

I like to call this technique, evocatively, “liquid finger,” as it allows me to “liquefy” the solid sound, divided into pitches according to the guitar frets, and obtain “fluid” textures covering the entire range of pitches. In fact, to create this idea of an “imaginary oud,” I decided to reserve one finger of the guitarist’s left hand for this purpose throughout the piece, ensuring the continuous exploration of this microtonal space without making adjustments or interrupting the piece’s continuity, which was essential to me.

After the first section, where the two basic materials were introduced, the slide and the first “arabesques” in the form of highly ornamented and timbrically elaborate small melodies, a second section with a more material character appears. Here, I play with the matter of the strings, working on the timbre of the sounds produced by the fingers when plucked and those generated by the slide when it trills over them. This section appears “tessellated” like a mosaic, with motifs from the previous section and some new ornamentations that embroider very short almost vocal melodies, reminiscent of Islamic art.

A third section opens as an extension of the previous one, introducing wooden sounds, as well as distortions and noises on the strings, which are again “tessellated” with the previous materials. A new hidden material appears in the very high register, touching the guitar strings near the body, a part of the instrument that is not normally used in performance but to which I wanted to give a symbolic and extremely special meaning. These small “drops,” which initially seem almost imperceptible, gradually reveal themselves, emerging from a weave of great density. In this section, there is a frenetic delineation of the material, with increasing levels of activity and percussive sounds beating on the instrument’s mouth.

Finally, the last section appears, stripped of the previously presented material, moving between improvisation and fixation, with high levels of ornamentation and bending, supported by the use of microtonality provided by the slide. The “drop-sounds,” which emerged from the previous section, are now the only material played by the guitarist, who places the instrument between the legs as if it were a cello. This way of playing the guitar hides a “scenic” and formal intention in terms of a paradigm shift, as well as facilitating the interpretation with two or more fingers on the string pieces connected to the pegs, allowing the sounds to blend with the slide, creating a dreamlike atmosphere leading to silence.

The collaboration with Pedro Rojas-Ogáyar continues with “Epitafio de Don Quijote,” where the guitar is joined by the flute, clarinet, soprano, and actor. Could you provide more insight into this piece?

A year later, I worked on a new chamber music project for the guitar with Pedro and Ocnos, “Epitafio de Don Quijote.” In this case, it’s almost like a chamber opera scene, dramatizing Cervantes’ well-known text corresponding to the inscription on the imaginary tomb of Don Quixote. I was interested in the idea of a fictitious epitaph that resonates with the life of a hero, or rather, an “anti-hero” like Don Quixote. I composed this piece as a musical theater, using the instruments, especially the guitar, as if they were the “sonic scenery” of the piece, creating atmospheres and materials that evoke shadows and ashes, like the remnants of a great castle in the air turned into ruins. Both the guitar and the bass clarinet are prepared with various materials such as water, tubes, pieces of plastic, and metal. There is also a quote from the piece “Mille Regretz” (Song of the Emperor) by Luis de Narváez, one of the key works in the history of music dating back to the time of Don Quixote, closely related to the Spanish vihuela, the ancestor of the guitar.

What considerations did you take into account when writing for the guitar as a chamber instrument compared to solo repertoire?

Orchestration work is a significant challenge in search of balance with the rest of the ensemble. On the other hand, it is also fascinating to explore convergences and divergences between the guitar and other instruments and voices. I find it particularly stimulating to approach sounds that recall other sonic sources through the guitar and vice versa.

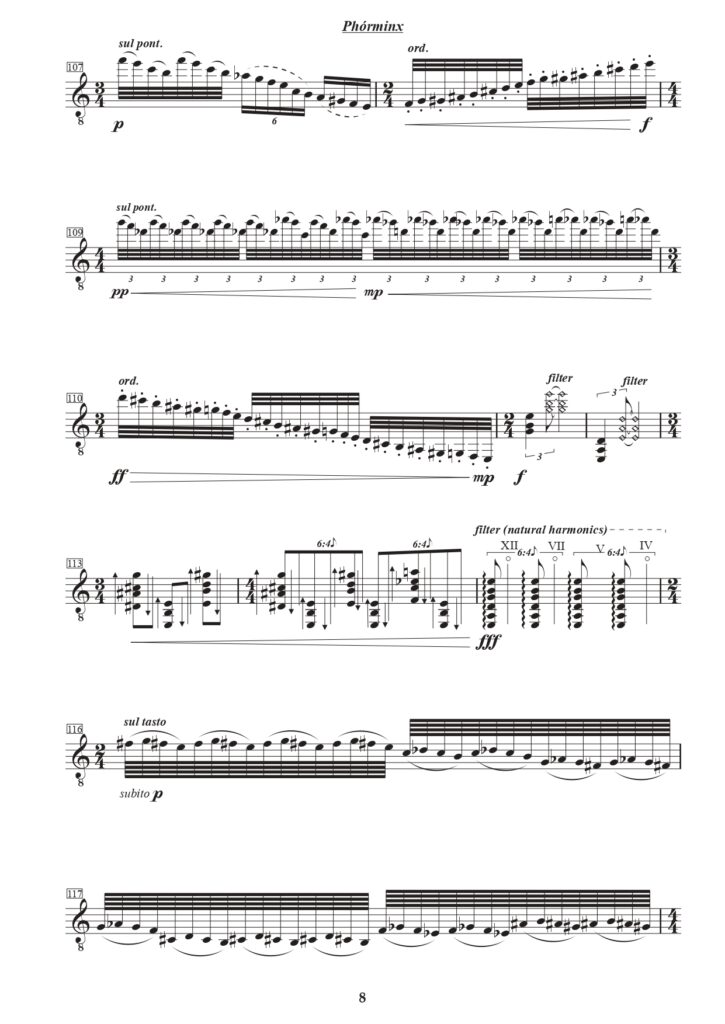

You returned to writing for the guitar in 2022, this time for the Slovenian guitarist Klara Tomljanovič. With Phorminx, you explored the instrument thoroughly: tuning, preparation, whistles, drumsticks, and a carillon on the guitar! Where does all this come from?

Before “Phorminx,” I returned to the guitar in 2020 with a piece for the Santorsa-Pereyra duo titled “Flow my tears.” In this work, I evoke the Renaissance universe, particularly the plucked string instruments of that period. Inspired by John Dowland’s homonymous ayre, the piece is conceived as a lament resonating with the pale colors of the Renaissance lute, based on a polyphonic timbral architecture with echoes, lights, and shadows.

However, focusing on “Phorminx,” a piece commissioned by Siemens Stiftung through the exceptional Slovenian guitarist Klara Tomljanovič, was a special creative opportunity thanks to her sensitivity to contemporary music. Klara has an enriching and intelligent vision of contemporary music, combining precise and virtuosic performance with a fresh expressiveness and stage presence, creating a unique connection between the performer, the audience, and the composer.

The phórminx is a Homeric lyre widespread in ancient Mediterranean cultures. It holds particular significance in the Tartessian civilization, considered by the Greeks as the first civilization in the West. This civilization settled in the southern Iberian Peninsula around the Guadalquivir River, in what is now the Andalusian region of Spain.

Aesthetically, I felt the need to create this piece due to my personal commitment to the concept of “radicalism,” which is extremely interesting to me. What does “radical” mean for today’s composer? Far from political fundamentalism, the word comes from the Latin “radicalis” and means “related to the root.” This concept interests me for my relationship with my deeper Iberian cultural roots, to create a new and personal musical universe. That is, how the Primitive or Ancestral can serve as fertile ground to propose something original projecting into the present and future. This theme is one of the main focuses of my work, as seen, for example, in my previous piece “Oud.”

The sounds of this ancient instrument are halfway between the lyre and the cithara. I can imagine creating an imaginary phórminx through the guitar. Rather than a strict reconstruction, it’s a personal approach to the guitar through a reminiscence of the phórminx, where colors and timbral textures play a significant role. It is a compositional work based on a free interpretation of musical archaeology.

To achieve this, the instrument undergoes some preparations that modify its acoustic behavior, such as Blu-Tack/Patafix, a carillon, drumsticks, an e-gong, and a pitch pipe—objects made of different materials that create a new musical universe. Additionally, I try to alter the usual tuning of the instrument to approach the non-tempered systems used in ancient modal and vocal systems. Different types of ornamentation and work with its resonance are also fundamental.

The conception of the lines closely resembles the human voice with its melismas and articulations. In fact, the phórminx served as accompaniment to rhapsodes, or reciters who sang the Homeric poems or other epic poems. Key elements are decorations that, through their various types and levels, represent a musical dramaturgy. This leads to metamorphoses or hybridizations of the material itself when the lines of force converge in different directions with different intensities. Thus, minimal musical gestures create an almost spiral musical current that expands its energy, thanks to the comparison with other elements coexisting in the space and time of its composition.

Despite your involvement in electronic music for several years, your guitar pieces don’t feature live electronics or tape.

This is indeed a field I would like to explore with the guitar, or rather with “the guitars,” in the future. I think there is enormous potential, and I would love to contribute to the repertoire of this formation, even in some larger multimedia projects. I hope this opportunity arises in the coming years, and I look forward to it.

You approached the electric guitar in 2020 with a 40-second piece for the KlangRoom project by Azione_Improvvisa Ensemble. What were, if any, the differences in approaching the two instruments?

The piece titled “Music 1 – COVID 0 with electric guitar,” written for Azione_Improvvisa—an ensemble I greatly admire—was a very special work, composed during a turbulent and difficult period for music creation and all other aspects of life. It was part of the KlangRoom project developed during the pandemic, representing a breath of fresh air and hope for the future through music and experimentation, seeking a shared sonic window. Working with the electric guitar was truly exciting because the instrument’s color palette and its native electronic possibilities are very appealing to me, offering something different from the classical guitar and presenting a new territory to explore. In fact, I must confess that I still have the desire to continue working on the electric guitar and its possible combinations with the extraordinary musicians of the Azione_Improvvisa ensemble. I hope this brief piece is the seed for future collaborations with this group, and the ideas we already have for the not-too-distant future will soon become a reality.