A composer and artist, Elena Rykova, explores a wide variety of genres in music and visual art, ranging from interdisciplinary and performance art to chamber and electroacoustic music. She brings together instruments and found objects, extending one through another and creating performative musical situations, often with a strong visual aspect. Her scores are characterized by innovative use of nontraditional notation, having been exhibited in art museums in her native Russia and abroad. She has written chamber works, music theatre pieces, and musical performances for major new music groups and festivals, like Wittener Tage für neue Kammermusik, WIEN-Modern, Mixtur, Tzlil Meudcan Festival, Ensems, among others. She is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Music Composition at Harvard University.

At Obiettivo contemporaneo we will talk about her numerous works for guitar, focusing on Asymptotic Freedom, a piece for six electric guitars recently performed at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse 2021.

Thank you, Elena for accepting our request.

Let’s start from the beginning: for the 2018 edition of the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik, Yaron Deutsch commissioned 12 studies for electric guitar to various composers from the contemporary music scene, including you.

This first collaboration resulted in Zigzag to Callisto, which contains the ideas that would later mark your style: a unique sound, characterised by unusual preparation and special effects. Where did all this come from?

When I compose, I prefer to work with a musical instrument myself. The action of touch is essential to me, and I would rather explore the instrument on my own than get acquainted with it only through a musician. The ideal option for me is to have both options available. I was a classical pianist for many years, and I have developed an intuition for searching for the desired sound through my hands and ears. In my practice, I extend this principle to other instruments, especially strings and percussion.

The first thing I did for the project with Yaron, I borrowed an electric guitar and prepared it with rubber bands to enable myself to play freely. During the exploration process, I transformed the instrument into something else; it became another type of guitar, where even a simple pluck on the string became unpredictable in its response since the rubber bands changed the usual behaviour of the guitar strings.

In my music, I challenge musicians to establish new relationships with their instruments through unstable sound material. Moreover, this renewed engagement with the instrument requires a different approach to time. I believe it calls for more attentive listening from both a performer and a listener. This way of playing and focused search through listening keeps me on my toes and inspires me the most.

The first piece I created in this direction was 101% mind uploading for prepared piano, percussion, and three performers. Since then, I’ve been pursuing this path towards deep listening and a highly engaged performing experience.

Looking back over your career and style, you started writing for guitar since 2015. Are there techniques and sounds that come close to your more recent works?

The first time I wrote for guitar, I also worked with preparation. It was a piece for a string trio: violin, cello, and guitar. All instruments were prepared with patafix, and I used only plucking technique, no bowing or ebow. That piece preceded 101% mind uploading and explored delicate sounds and their resonances. The colors of all three instruments constituted one palette of a meta-music box.

Another ensemble piece with guitar was Life expectancy. Experience #2. Your Moon written for guitar, cello, snare drum, objects and amplification. The preparation of the guitar in that piece was more extensive. It was the first piece where I worked with feedback. I created the relationship between the reverb box attached to the guitar and a mini-amplifier and singing into the corrugated hosepipe, one end of which I placed inside the guitar’s soundhole. When coinciding with the pitch of the feedback, the overtones produce “singing” difference tones.

So, I guess both pieces already have some noticeable traits of my later guitar works and musical interests.

In 2018 you received another request. To write not just one piece, but a work of almost one hour for six electric guitars.

Last August, in Darmstadt, the Ufa Sextet project performed Asymptotic Freedom for the first time.

How did you organise your writing work? How did you develop the initial idea present in the solo guitar study in such a large context?

I knew that I wanted to explore the sound world that I tapped onto with the etude further, so my starting point was to continue with the idea of the rubber band preparation. The project consisted of a shorter piece and a one-hour piece, which took off the first one. Working in these two stages was crucial because the first 12-minute piece established the sound world, and hence, I was able to see the multitude of possible openings into new sub-worlds within it. And then the lockdown happened but for my creative work on this specific piece, that was a blessing. Instead of three months, I got the whole year to work on the one-hour piece, and this amount of time is what allowed it to grow.

I didn’t take any other commissions that year because I knew this piece is exceptionally dear to me, and it needed my whole attention and presence. I always worked with my guitar at home, recording all my sessions into Reaper, listening to them, and composing the piece right there, without writing it down on paper. Then I allowed myself sometimes not to touch the work for weeks if I didn’t yet know where to go next. This luxury of time allowed me to take distance to the already written portion of music, and the next time I would come back to it, I knew exactly where to go.

The structure of the piece changed several times, and what I thought was a beginning eventually found a new location in the work. Six or seven months through, I started again to be in close contact with the guitarists of UFA sextet; we tested certain things and discussed the part that was already written. During this stage of the process, incredible discoveries started to happen on that front, like a sonic research with magnets that Samuel Toro Pérez and I were doing over Zoom. That was the last significant change in the piece: that specific sound material exploded in three different sections and constituted nearly a third of the whole work.

I was lucky to be on a grant that whole year that I was writing. I didn’t have to teach or do any other work. That is why I dedicated my entire year only to one project. This type of working condition has never happened to me before. Another part that was crucial to the project’s success is the collaboration and friendship with the musicians of UFA sextet. Personal connections changed my relationship with the project because I was writing for people I sincerely admire and enjoy spending time with, with whom I shared some lovely moments. It was an unforgettable year for me and my most magical project so far with an unbelievably fantastic sextet, and I’m honored that it carries the name of the town where I was born – UFA.

Besides being a composer, you have written many texts, poems and are involved in visual art.

In fact, seeing the scores of your pieces, it is as if you wanted to represent in pictures and lyrics the sounds you are imagining. How much have these “parallel” arts influenced your way of composing?

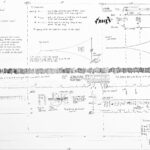

I have experience in visual art and dance, and I’m often collaborating with other artists from various disciplines. I always seek a different approach to creation as it always teaches me a new way of seeing things, a new perspective. Also, I believe that writing music is interdisciplinary by nature. We naturally engage in expressing ideas from a visual domain into music and translating the latter into visual language on paper. But what if you explore a new type of sonority with a found object that no one used before? In that case, there is a necessity to invent a language to write it down. I love drawing and painting. I also tend to think of a score as an art object that can inspire performers and tell them something about its world even when they first look at it. It becomes especially relevant when I can’t travel to the performance, then my scores speak for me through the drawings, symbols, and texts. I always create my scores by hand (and it takes a lot of time to draw them), but the notation itself is mixed. Whenever necessary, I use the traditional notation, but most often, I combine it with other graphics and drawings that might be necessary for the sound and the world of the piece.

Since several years you live in Boston, where you carry out various academic activities.

How is the contemporary music scene developing in the US?

The contemporary scene in the US is quite different. In most cities, it is centered around universities with excellent master and PhD programs but most often they don’t have any ensembles in permanent residence, so they have to invite other ensembles to come for a week residency to workshop the pieces and then perform them in a concert. There are some exceptions like UCSD, which has a fantastic performance department with incredible musicians, or in the cities like Chicago or New York, there is a vibrant music scene too. Some musicians in the US also try to freelance, but it is much harder in general than being a freelance musician in Europe because there is no state support for arts, and on top of that, the cost of living is much more expensive here.

Would you like to tell us about your future projects?

This year is going to be quite busy, which is very exciting. I have three upcoming commissions for chamber music pieces. The first one is for Moscow contemporary music ensemble in Russia by Aksenov Foundation, where I am experimenting with amplification and space. Then I’ll be writing for ensemble Schallfeld (a commission by IEMA and Mixtur festival). After, I will be working on the piece for Nikel ensemble commissioned by I & I Foundation. Besides, I will also have a premiere with the ensemble Proxima Centauri commissioned by Radio France.

Right now, I’m working a lot with my voice, and I’m going to continue moving in that direction. The singing, melodic quality already revealed itself in Asymptotic Freedom II, and I’m curious to see how it will express itself in other formations. I’m also curious about how my next piece for an electric guitar will sound. I haven’t yet decided what exactly I am going to explore there, I usually decide in the process. Of course, the experience of the recent guitar projects has been internalized; it is in my veins. But in each new piece, I always go towards the unknown territories in order to try something new, to challenge myself. So, I guess there will be a palpable connection to my guitar pieces, but I also expect some tangible change to happen as well.

Originally published on Guitart n. 105