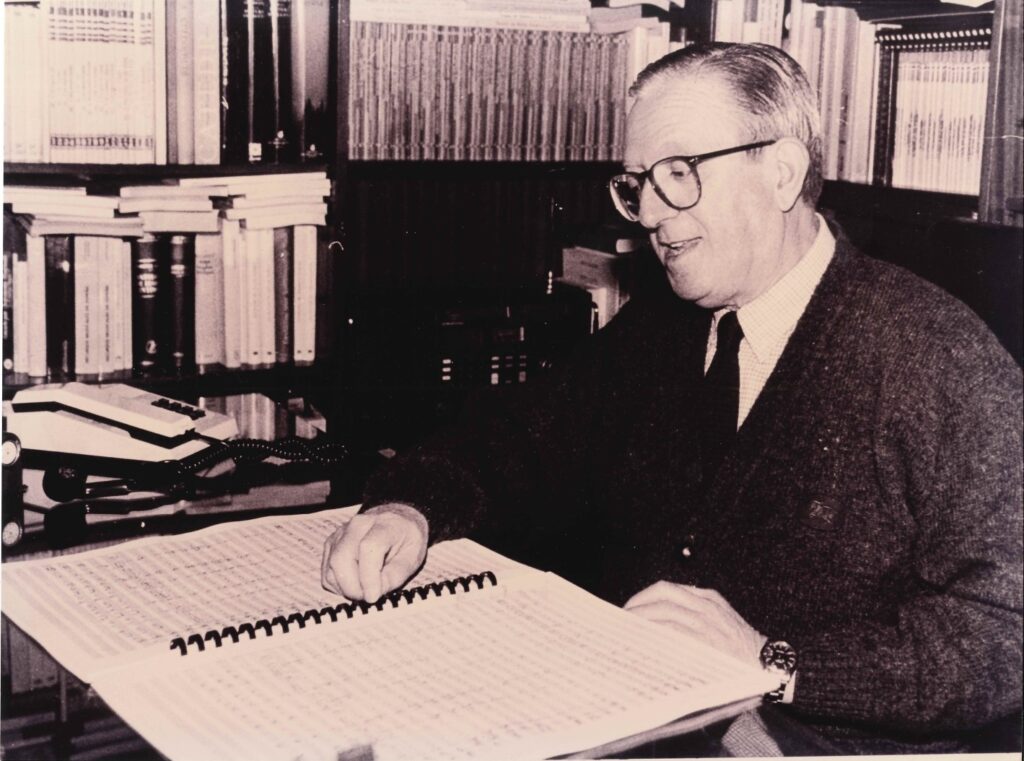

With today’s interview, we wish to remember and pay tribute to Manuel Castillo (1930–2005), Andalusian composer and a key figure straddling the divide between Spanish nationalism and the avant-garde that defined his era — in particular, the group known as the Generación del ’51. Castillo wrote extensively for guitar in a variety of contexts: from solo works to chamber music, from duos to concertos with orchestra. For a long time, little was known about these works — until Jesús Pineda, in 2015, undertook an extensive revision of the entire guitar repertoire written by the Sevillian composer. This conversation helps us uncover a long-forgotten archive.

Jesús, thank you for accepting our invitation. Your work began in 2015 with the idea of creating an archive of all the material written by Manuel Castillo for guitar. The result ended up being much more elaborate than expected: a monographic album, a critical edition, and a doctoral thesis.

To be honest, my first encounter with Castillo’s work actually took place in 2009. Motivated by the curiosity surrounding a legacy both close and yet strangely unknown, I decided to dedicate my master’s thesis to studying his compositional language. This eventually led to several articles and, ultimately, to my doctoral dissertation, which presents an analytical study of his complete works for guitar and their impact on the guitar community. However, details regarding how well his language fits the instrument, as well as issues stemming from his particular compositional style, were only sketched out theoretically in that document. It included no concrete proposals, practical solutions, or clarifications of the challenges I had identified. For these reasons — and also because part of the material was still in manuscript form — I decided to produce a critical edition. My aim was to include everything that might contribute to a deeper understanding of this heritage, thus helping ensure its preservation and dissemination.

The monographic recording, on the other hand, was conceived as a personal interpretative contribution, designed to support the theoretical foundations laid out in the editorial project.

Despite the long list of works dedicated to the instrument, Castillo’s music remains largely unfamiliar — even among guitarists. We know he wasn’t fond of speaking about his compositions, and introductory descriptions are often missing. What have you discovered that adds to what little was already known?

Castillo devoted a substantial portion of his output to the piano (his own instrument) and to the organ. In fact, there’s been solid fieldwork on that repertoire, and many of his pieces have been recorded and performed in dedicated concerts. On the other hand, when I turned to his guitar music, I quickly realized there were no prior studies, and almost no recordings of his works.

Without going too deep into why that might be, what’s clear is that there was a general lack of information. I therefore began to gather materials from various sources: from the premieres of the Sonata para guitarra and the Concierto para guitarra y orquesta, where introductory lectures had been given; from the brief program notes of Kasidas del Alcázar and Vientecillo de primavera; and from some of Castillo’s statements in various interviews.

Still, most of these declarations were rather superficial regarding his compositional process. They focused more on general evaluations of the character of the works or the motivations behind them. This made it necessary to carry out a detailed analytical study — one rooted in the music itself and attentive to the aesthetic influences Castillo had absorbed.

This effort took concrete form in my thesis, which explores a wide range of elements: from stylistic aspects to harmonic, formal, rhythmic, and textural approaches; from writing techniques to the adaptation of the music to the idiomatic characteristics of the instrument.

Interestingly, I found his guitar output to be much more stylistically diverse than I had initially imagined. Since these works were composed in his mature period, one can detect traces of several artistic movements — impressionism, nationalism, neoclassicism, serialism, and tradition — which, when filtered through his own artistic motivations, coalesce into a distinctive personal language.

At the same time, although he made a deliberate choice to avoid exploring some of the more experimental or timbral resources typically associated with the avant-garde (especially timbral or percussive effects), his music still fits the guitar very well — something not always true for non-guitarist composers. He knew how to exploit many of the instrument’s conventional expressive qualities.

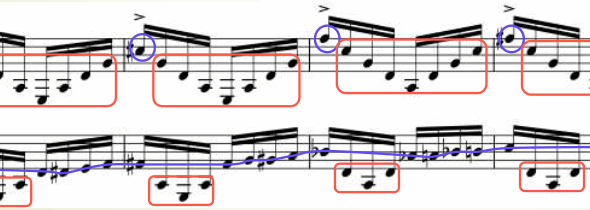

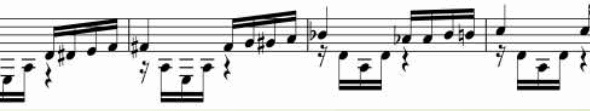

Lastly, some pages in this corpus feature extended passages written for a single melodic line, giving the guitar a purely monodic treatment that would seem, at first glance, to underuse its polyphonic potential and reduce its harmonic richness. However, a closer look reveals quite the opposite: many of these seemingly simple lines contain an underlying contrapuntal texture, in which two or more voices intertwine to create a hidden polyphonic fabric.

This aspect is hard to appreciate at first glance in the original notation, as the direction of the stems does not clearly distinguish the voices. In this context, harmony — understood as the vertical result of that polyphonic structure — is actually built from melodic development, from a horizontal rather than vertical perspective. This approach is one of the most characteristic features of Castillo’s compositional style.

Let’s talk about the critical edition: what changes did you make to the manuscripts?

Mainly three. Firstly, and in relation to what has already been said, a thorough revision of the actual polyphonic framework of certain pieces was carried out (particularly the first and third movements of the Tres Preludios and the Sonata para guitarra, as well as several passages from the Quinteto con guitarra), with the aim of clarifying the textures by proposing an appropriate separation of the voices through the correct positioning of the note stems.

Secondly, and perhaps as a consequence of the fact that during the period when he wrote most of his guitar works Castillo received a large number of commissions, there are some writing errors that have been reviewed and corrected. This occurs mainly in the Quinteto, where there are occasionally notes that do not match the serial scheme used as thematic material or its polyphonic imitations. Castillo was extremely meticulous in applying scholastic counterpoint, and it is striking when a note clearly diverges from the norm, strongly suggesting it was a small oversight. Similarly, in other pieces we find minor mistakes in identical repetitions or in transposed imitations in other voices. All of this is detailed and the reader is informed by either proposing the correct note directly, or (when there is no clear evidence whether it’s a mistake or a deliberate choice by the composer) offering an optional “ossia” version along with an asterisk on the original note or passage, allowing the performer freedom of choice.

Thirdly, a fingering plan was developed based on the aforementioned premises: clarifying textures and respecting voices through the overlapping or separation of polyphonic parts; articulation proposals for melodic motifs based on compositional criteria; presentation of various solutions for performing fast passages or non-idiomatic mechanisms, such as continuous five- or six-note arpeggios; and suggestions to help create the atmosphere and general character of a given fragment, such as cantabile melodic developments in some slow movements by using wide fingerings along the same string. All of this was done with the goal of making this repertoire more accessible to any interested guitarist.

Finally, and only in certain sections of Kasidas del Alcázar (written for two guitars), there is a more balanced distribution of the musical content between the two guitars, in order to facilitate certain passages, support legato phrasing, allow the sustaining of specific notes/chords, and generally contribute to the harmonic clarity of the work and the use of the acoustic-resonant potential of both instruments.

If we were to delve into Manuel Castillo’s style, we would find a blend of Spanish influences and an irregular use of symmetrical scales, serialism, and harmonies reminiscent of the avant-garde of the second half of the 20th century. This mix of elements creates a fluid identity for his intentionally unstable music. Considering all of his guitar works, do you think his style evolved over time?

As I mentioned before, I believe his language was forged from many influences and went through various creative phases (as also happened with many other composers), but there is undoubtedly an underlying essence that unifies and gives coherence to this blend of styles, forming his distinctive hallmark.

As for the guitar repertoire, since it was composed almost entirely in a later period, many of these influences can be appreciated, though not exclusively tied to any single one. From this perspective, the programmatic works Kasidas del Alcázar and Vientecillo de primavera move in a realm close to impressionism, due to the evocative poetic content that inspired them. The Tres preludios and the Sonata para guitarra evoke Bartókian reminiscences and procedures derived from neoclassicism in combination with his own techniques. Canción de cuna (Lullaby) is clearly linked to an earlier phase closer to tradition and Andalusianism, which can also be sensed at times in the Concierto para guitarra y orquesta. And as for the Quinteto, as already mentioned, he continues to flirt with serialism, although treated very freely and interspersed with regular elements in his language, such as the frequent use of chromaticism and a taste for contrapuntal elaboration.

Perhaps for all these reasons, his body of work for guitar is a compilation of nearly all of his influences and offers a comprehensive view of his creative identity. An identity that adapts to the communicative goal of each piece as its primary purpose, thanks to the conscious use of this blend of acquired languages—just like a visual artist uses all the materials at their disposal to recreate and shape their work.

In many cases, as we know, what we hear is not only the result of the author’s creativity and personality, but also of the context in which they lived. In this case, let’s talk about Seville—a city lacking cultural resources to support its artists, in a period of significant backwardness. How do you see his position within such a complicated environment?

Castillo had a phrase that summed up his attachment to the city: “Seville gives me a point of freedom.” The truth is that, although he spent virtually his entire life in his homeland, he always stayed up to date with the avant-garde scenes that were emerging elsewhere (particularly in Spain’s main composition hubs: Madrid and Barcelona), thanks to the consistent contact he maintained with his generational peers. Moreover, many of his works premiered in those cities.

However, according to his own statements, living far from these focal or nerve centers allowed him to develop his creativity with enough freedom to avoid conforming to any passing trends due to psychological pressures. At the same time, it spared him from rivalries or jealousies that were foreign to his nature and personality.

Likewise, Seville—and by extension, Andalusia—paid tribute to him during his lifetime with numerous honors and awards (he was named “Favored Son” of Andalusia in 1988 and of Seville in 1997), and commissioned him to write many works that were premiered and recorded primarily by the Real Orquesta Sinfónica de Sevilla (of which he was also a member of the Advisory Board).

In terms of education, he held the composition chair alone for more than twenty years, mentoring more than one generation of young composers. He passed on to them all the innovations taking place in the rest of Europe and became a pioneering reference in Andalusia, especially considering that, at the beginning, no similar composition chair existed elsewhere in the region.

At the same time, he did excellent work as director of the Conservatorio Superior de Sevilla, promoting the institution’s image in Sevillian society and championing contemporary music across various fields.

On another note, conductor Juan Luis Pérez said that Castillo served as a bridge between the era of Turina and Falla and the new generations of Andalusian composers, describing him as a “necessary composer” in a post-Civil War period marked by uncertainty, where the dominant references were still traditional canons based on folklore and fin-de-siècle nationalism. I believe Castillo transcended these frameworks and, thanks to his moderate yet forward-looking convictions—aligned with the identity of the Generación del ’51 (which sought new languages in line with advances in Central Europe)—he brought fresh air to a Seville still rooted in the past, both through his artistic output and his legacy as an educator and cultural leader.

Undoubtedly, the contribution and the rewards were mutual between the city and the composer, as they helped enrich the musical culture of the local population and opened the way to new horizons.

Originally published on Guitart n.110