Julien Malaussena, born in 1980, is one of the most eclectic and creative composers of his generation. Trained in Paris with Jean Luc Hervé and Pierre Farago, he studied electroacoustic composition, sound engineering, and orchestration, before earning a Master’s degree in Musicology with Ivanka Stoianova. His works have been performed in France, Israel, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany, Russia, Austria, Brazil, the United States, Turkey, and Spain. Analyzing his catalog, one can notice his interest in the guitar, present in both solo and chamber music contexts. After his experience with the electric guitar in the piece Other Space, dedicated to the Nikel Ensemble, we interview him to delve deeper into his already substantial repertoire, where our instrument plays a leading role.

What is your experience with the instrument? Did you study guitar before dedicating yourself to composition?

Yes, it was the instrument through which I discovered music. I started when I was about 12, after hearing an electric guitar solo on a CD.

Are there composers, schools, or artistic movements that you consider a reference?

Not entirely. I see my style as an encounter with the music of Lachenmann, Romitelli, Amon Tobin, Billone, Czernowin, and many others. However, I think there is a significant aesthetic difference between my writing and theirs. Electronic music has also always had a big influence on my work, and this influence is probably still growing. Sound design techniques and sound engineering really stimulate my imagination, and I constantly try to improve these skills. At the same time, I am increasingly obsessed with Webern’s music, which is probably paradoxical.

Could you tell us how you approach writing a piece? Do you follow a methodical process, or are you inspired by an idea that you then develop into a discourse?

I don’t think I have a “personal grammar.” I work with a number of sounds that I classify into categories based on the dynamic functions I want to achieve. From this classification, I follow certain parameters:

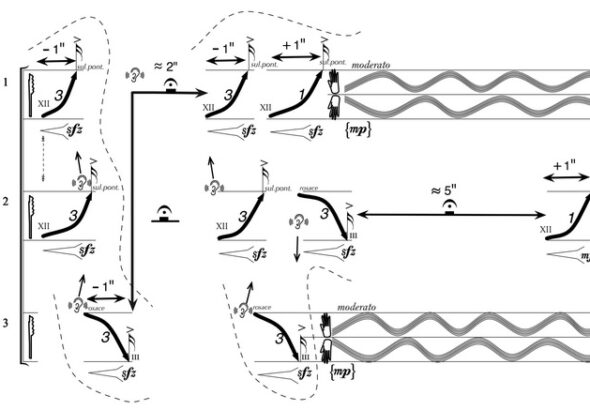

- With the performers, I search for material that inspires interesting sound relationships.

- From the results obtained, I develop a small number of “situations,” usually between three and seven.

- I analyze different possible combinations to create a larger sound context.

Once I establish principles that can bring all the ideas together, I begin writing. Somehow, I navigate through the small galaxy of musical situations I have previously created.

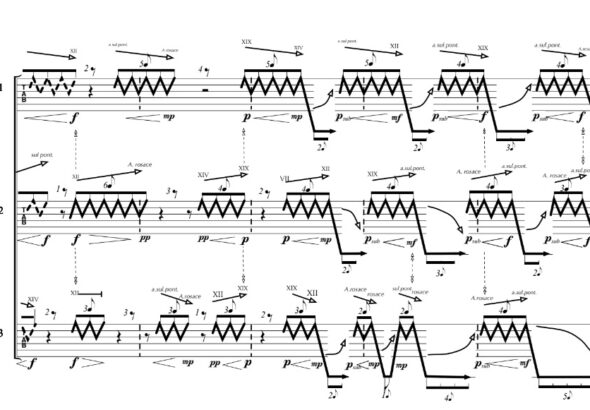

In your works for guitar (Introduction au timbre et à l’énergie for three guitars, (EP) Scra’p for solo guitar, Exigüe (Contigüe) for guitar and string trio), we can observe how the timbral center around which all ideas are developed is what we commonly call “noise,” achieved through the use of knives, coins, pencils, or by rubbing hands on the strings. Can we consider the union of gesture and sound as the real leitmotif of your compositional process?

Exactly! As mentioned before, having different categories of sounds that dictate energy and dynamics makes it very complicated, if not impossible, to reproduce certain materials on the guitar using traditional techniques. Therefore, I prefer to transform the instrument to find this “function-energy,” which creates a completely personal aesthetic. It’s the same core principle in my more recent electric guitar piece de toucher de lignes, written for Carlo Siega.

Could you tell us about your work (EP) Scra’p? What were the ideas, timbral choices, and formal organization of the piece? How did your relationship with Remy Reber evolve?

The piece was written in 2013 for a project that ultimately didn’t take off. Not wanting to abandon the proposal, I looked for a guitarist who would support my ideas. Remy “took ownership” of the piece brilliantly, performing it in concert two years after the final revision.

The initial idea was to conceive a dialogue or duo between the two hands, as if they were independent voices. From this, I developed each section by writing one voice at a time, combining gestures as the results emerged. I did not plan a form—I never do, actually. I prefer to relate musical situations in an entirely free manner, without adhering to a specific structure.

How was your experience with the electric guitar? Did you encounter any specific difficulties while writing for this instrument?

The electric guitar fits very well with my musical language. By the time I started writing for it, I already had a clear idea of its characteristics, having played electric guitar for many years in the past. The experience was incredible, thanks to the work of Yaron Deutsch, a musician I admire immensely, who always manages to bring out a deep understanding of my music.

What do you think are the main differences between classical and electric guitar? What adjustments did you make to ensure your aesthetic remained consistent?

Beyond the technological aspects, I had to deal with substantial differences, especially when imagining and organizing the various sound elements that interested me.

For example, one major divergence is resonance: since the electric guitar can sustain sound for much longer, I based my work on this characteristic. Amplification, on the other hand, opens up a completely different sonic universe, allowing dynamic exploration from pianissimo to extreme intensities. In that case, I had to carefully integrate the instrument into an ensemble, applying various filters to create a unified sound.

Overall, it felt like starting from scratch. Many techniques used on the classical guitar, like the guero technique or various percussive effects that I used in (EP) Scra’p, cannot be reproduced on the electric guitar. It was a completely new exploration that allowed me to innovate my writing.

In contemporary music, the electric guitar has become a cornerstone in many ensembles. With its vast range of effects, timbres, and dynamics, do you think the classical guitar still has a place in this field? How do you imagine the guitar of the future? After your experience with Ensemble Nikel, do you think you will continue writing for classical guitar?

I don’t think there is a “clash” between the two instruments. The electric guitar, despite its immense range of sounds, will never replace the classical guitar. As mentioned earlier, certain techniques are virtually impossible to replicate on the electric guitar.

Moreover, the electric guitar requires a different sonic context, with specific amplification. In an ensemble, it dramatically alters the chamber texture it is part of. Both instruments have great potential, and their future depends entirely on the creativity of composers.

In 2021, you wrote de toucher de lignes for Carlo Siega. The piece was presented at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt. How did the collaboration unfold? How did working with Carlo influence your approach, and how did your writing evolve between Outer Space and de toucher de lignes?

Carlo lives in Italy, and I live in France, so during the composition phase, our collaboration was remote. Since the guitar is my instrument, I didn’t need to experiment much with him. We mainly exchanged ideas about his pedals, different guitar models, and the possibilities they offered. This phase of discussion was very stimulating and crucial in determining the choice of materials and instrumental techniques used in the piece.

I then composed independently and only reconnected with him once the score was finished. After the first performance, following the experience gained during rehearsals with Carlo Siega, I slightly improved the notation and rewrote the technical sheet.

It’s hard for me to pinpoint exactly how my writing evolved between Outer Space and de toucher de lignes. These were two very different projects. Outer Space was written for a cine-concert with Peter Tscherkassky’s film, where the relationship between sound and image was fundamental—I wanted the music to convey my personal interpretation of the film, which also had a political dimension. In de toucher de lignes, the focus was purely musical.

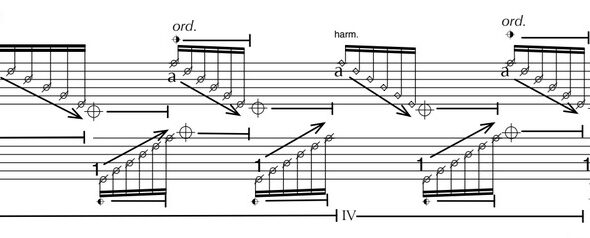

Among the indications in the score, there is the use of an expression pedal and a whammy pedal. Could you explain their role in your composition and how you structured this piece?

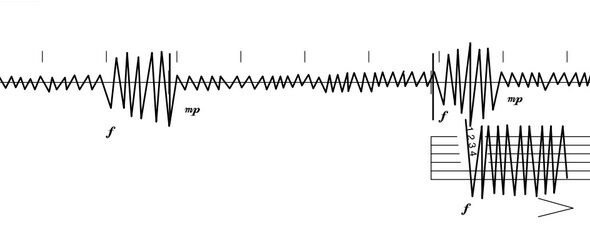

The core idea was, in continuity with my solo classical guitar piece, to search for instrumental materials and gestures that allow one of the two hands to remain free. I wanted to create a hand duet rather than a solo piece, with the whammy pedal and pitch switches adding a third dimension. I also aimed to develop material with resonance control.

During the composition process, I moved between direct experimentation, improvisation, and composing away from the instrument. In this piece, I focused a lot on the impression of stretching and friction in the sound material, working with energy categories like stretching, rewinding, projection, and waves.

There is an almost symmetrical relationship between the pedal settings (the whammy is set on a perfect fourth, with three pitch shifts at +50c, -50c, and -100c) and the guitar’s tuning (D-10c/A/A+50c/F#/B/B+50), reinforcing the presence of fourths and quarter tones. This allows for a continuous tactile space (using slide guitar or thimbles along the strings) and a dynamic interplay between foot controllers (expression pedals and switch pedals).