Continued from PART I

II The Musical Poetics

In general terms, the poetics of Scodanibbio, the composer, can be understood according to three frameworks. The first involves the idea of renewing instrumental resources, through the exploration of uncommon sound production techniques. Scodanibbio draws on his experience with the double bass to develop original execution mechanisms, accompanied by compositional operations used by composers of his time. The second framework concerns the virtuosic mechanism that acts as a vehicle for the development of the writing, in a continuous passage between innovation and tradition. The composer does not escape the historicism that pervades the late 20th century, but filters it through the explorations of his time. It is worth noting here that musical practice has continuously been supported by the inventive capacity of the performer, not only in generating unusual sound materials, but also in the systematization and optimization of instrumental resources. Scodanibbio relies on vocality as the gravitational axis of that connecting technical virtuosity, formalizing it under the shadow of the lyrical spirit of the poetic-musical tradition of the West, even though this may occur in vocal forms that resemble the ritual songs of civilizations far from his cultural origin. The compositional dimension in which he has probably contributed most significantly, however, is in the interest he directed towards working with the string: an immediate acoustic study object and an apparently inexhaustible source of expressive resources. Finally, all of these poetic mechanisms materialize into some compositional strategies and form a third poetic framework. In this way, improvisation as a method of formalization, the consideration of the body-instrument as a creative research device, and the approach to oral tradition practices are vehicles that allow for an updated theoretical reflection, starting from the musical practice itself.

Instrumental Renaissance

The idea of “Instrumental Renaissance” suggests the renewal of musical writing through instrumental practice, drawing inspiration from the historical period situated between the 15th and 16th centuries, when the arts flourished significantly in Europe, particularly in Italy. Through this term, Scodanibbio would have given life to his creative research.

This concept is shaped around the activities organized in the Rassegna di Nuova Musica festival, dedicated exclusively to soloists. In practice, it involves delving into the creation of works for instruments that had remained on the margins of the avant-garde explorations of previous years (such as trombone, tuba, percussion, double bass, for example). A historical phenomenon in musical practice which, according to Scodanibbio, resembled the Baroque period for string instruments1. Indeed, Bañuelos emphasizes that part of his fraternal bond with the double bassist originates from the fact that they worked with instruments with a similar historical situation:

"I believe he felt a strong affinity [with the guitar] starting from the double bass. We felt that they were instruments, let’s say, ‘brothers’ in a certain way. Because they were like ‘ugly ducklings’. They were the newcomers, just entering the world of contemporary music. Instruments that were, as they would say now: emerging. And in this sense, yes, there was that complicity and brotherhood between those instruments that were rising and had to show and prove they had resources. Only then could they enter the Instrumental Renaissance. The term is very beautiful."2

As a performer, Scodanibbio places himself within this search for instrumental rebirth through the double bass,3 from which he develops a reflection according to which the task of the composer and the performer is to return to the intimate, almost loving relationship that has always existed and that underscores the singularity of the work. In the face of the decline of the avant-garde, their attempts to break with dogmas, and their homogenization, Scodanibbio sees a possibility in the conciliatory plurality. This idea builds a bridge to the postmodernism of the late century, and this becomes evident when he states that we must “accept influences and reminiscences, remember our past and our emotions.”4 It is within this ideological context that the idea of Instrumental Renaissance (Rinascimento strumentale) is situated.

On the other hand, the sought-after innovation is opposed to the traditional avant-garde that prioritized the idea, the process, and the discourse: “Music is not a theorem or a lecture, and it returns to being as it was before, but in new forms.”5 The response is implicitly directed at integral serialism, represented by the main composers linked to the Darmstädter Ferienkurse: “During the avant-garde, music was guided by an idea. There was a lot of theory and little music, and thus concepts and ideas from other arts and sciences were transported to music.”6 For him, the task was to integrate the composer, the performer, and the listener: “In this sense, I believe the avant-garde art was a cold movement; instead, today we recover the pleasure and beauty, and ultimately the eroticism of music.”7 The musical experience concerns more of a physiological concern and less a purely rational exercise; it is about seeing the instrument as another possibility: “The new and vast solo literature of these years seems to me the testimony of how the instrument itself is the key to research towards a possible musical evolution.”8

Between Innovation and Tradition

We have already seen how references to the great 19th-century guitarists are frequent in Scodanibbio’s imagination, but these types of historical resonances are formally embodied in his works. In the conciliatory space allowed by the musical thought of the late 20th century, the composer must confront apparent contradictions. On one side, there are attempts to mediate with the past after the abrupt breaks and radicalism of the avant-gardes in the second half of the century. On the other, there is coexistence with experiences that expand the spectrum of possibilities and push the musical language to the limit, to the boundaries of artistic creativity.

In Light of History

The ghosts of the 19th century appear in the way vocality in singing is transfigured in the score. The shift from expression to abstraction occurs through the prism of the lyricism of bel canto. Some formal strategies employed by Scodanibbio resemble the lyrical device that can be found with some frequency in the concertante music of the so-called Classical/Romantic period, primarily in Italy; for example, what can be found in works such as Sonata No. 6 in E minor, op. 3, M.S. 64, for violin and guitar by Niccolò Paganini. In Alisei (1986), Scodanibbio uses harmonic sounds, passing through an ornamental lyrical treatment, in conjunction with cadential forms. In this sense, the abstraction of concrete material finds a sensitive space in the aestheticized form of 19th-century operatic singing, which, in turn, combines lyricism with technical development. This is how certain operations inherited from the past allow for the articulation of the musical event in works such as Sei Studi (1983), for solo double bass: melodic bursts and harmonic arabesques (Studio 1, “Joke”), arpeggios linked to the contemplation of harmonic chains (Studio 2, “Dust”), or the programmatic and extra-musical reference (Studio 4, “Faraway”). It can be said that, in a sense, Scodanibbio approaches Giovanni Bottesini (1821-1889), the 19th-century double bass virtuoso, who, seeking to reposition his instrument in the soloist category, resorts to the lyrical potential of the cello by exploring the high, cantabile register of the double bass.

If this observation were true, Scodanibbio’s writing would diverge radically from the traditional avant-garde resources of his time. Let us recall, for example, the uncompromising rejection by Luigi Nono (1924-1990) of the use of operations that could suggest references to “bourgeois music.”9 Certainly, this is a point of divergence between Scodanibbio and the post-war generations. In fact, from the perspective of traditional avant-garde, his work could be perceived as an effort to trivialize the concrete material through conventional formal perception strategies.

In the Shadow of the Contemporary

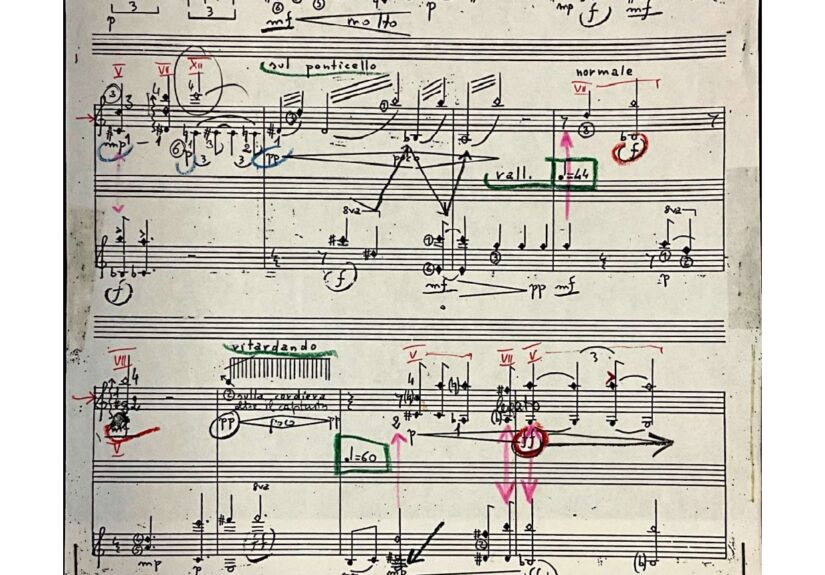

Despite his constant eclecticism, Scodanibbio’s work reveals moments of closeness to the writing of Salvatore Sciarrino (1947–), a composer who has had a strong influence on composers of this period. One link is found in the conception of “a sound close to the inaudible,” whose aim is to question aspects related to listening.10 Although not always, the use of harmonics as the primary material is an indicator of this research. In “Voyage continued”, the third composition of Voyage that never ends (1979-1997), Scodanibbio explores these perception relationships. Another aspect is the “pedagogy of form,” which in Sciarrino is linked to the theme of listening11, and in Scodanibbio, it merges with the idea of the progressive development of sound material through the components of improvisation. In Sei Studi (1981-1983), for solo double bass, this aspect can be clearly perceived. Thus, the transfiguration of forms inspired by classical tradition, aimed at constructing “sound organisms,”12 is one of the points of agreement between the two composers. More superficially, the arsenal of perception that Sciarrino explores, such as harmonics in tremolo and glissando or the multiple combination of timbres13, in Scodanibbio transforms into the object of instrumental play and combinatorics.

The Secret of the String

Scodanibbio’s most original aesthetic contribution may lie in what we can call the “secret of the string.” Indeed, the idea of Rinascimento Strumentale (Instrumental Renaissance) recalls the artistic flourishing that occurred between the 15th and 16th centuries, but it mainly rests on the parallelism with the evolution of Italian instrumental music during the Baroque period, particularly in the development of string instruments in the works of Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) and Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)14. That is, the idea of musical innovation proposed by Scodanibbio traces a historical line that spans the last five hundred years and is accentuated in more recent figures of the double bass such as Domenico Carlo Maria Dragonetti (1763-1846), Giovanni Bottesini (1821-1889), and ultimately Fernando Grillo (1945-2013).

The reflection of composer Maurizio Pisati (1959-) regarding Scodanibbio seems to align with this when he asserts that the uniqueness of his work lies in the invention on “the string” and states: “There, Stefano opened a laboratory that he never closed.”15 From this perspective, Pisati emphasizes that Scodanibbio’s work for guitar immediately enters the realm of the hands, not only due to the deep understanding of the strings tuned in fourths but, even more so, because of the secret of the string itself.16 As we will see later, the almost systematic exploration of the first natural harmonics of the guitar in works like Techne or Verano de Suerte allows for a focus on a sound material that had been scarcely referenced in earlier works.

There seem to be no precedents in the twentieth century for the application of this material in entire sections of a work, as was done by Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829) in Otto Variazioni Op. 6 (1811) or Fernando Sor (1778-1839) in Étude Op. 29 no. 21 (1827)17. Once again, it is confirmed that Scodanibbio’s aesthetics are based on the idea of innovation by striking with the elements of tradition, while mobilizing a deep reflection on instrumental practice in the current compositional context.

Compositional Strategies

Scodanibbio employed numerous compositional resources to complete his works. However, three stand out and highlight aspects of his uniqueness: improvisation as a method of formalization, reflection on the musician’s body in relation to the instrument, and finally, hybridization with music of oral tradition.

Improvisation

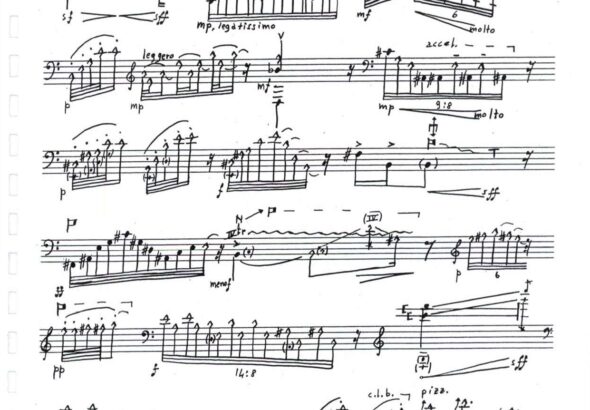

In a metaphorical sense, improvisation was one of the configurations of the journey for Scodanibbio. From this perspective, creation in situ seems to have been a means of venturing toward horizons rarely explored by traditional writing. Certainly, it was useful for the exploration of new instrumental possibilities as a sonic laboratory, but it was also a method of formalization: improvisation was understood as a procedural path toward the artistic idea and the sensory experience. As suggested by guitarist Magnus Andersson (1956-), this seems to have been the strategy most used in the composition of his guitar works, particularly in Dos Abismos.18 Another clear example is in Studio 6 “Farewell”, whose development is openly based on improvisation, as the composer himself emphasizes:

“This study is of an improvised nature. Only some phrases are suggested here, which can be repeated, elaborated (while maintaining the use of only pizzicato harmonics), and alternated with one another.”19

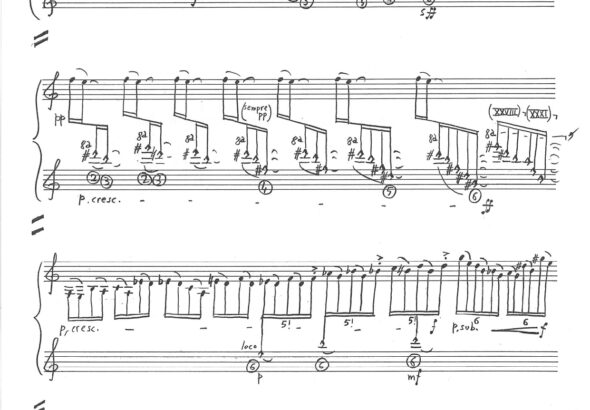

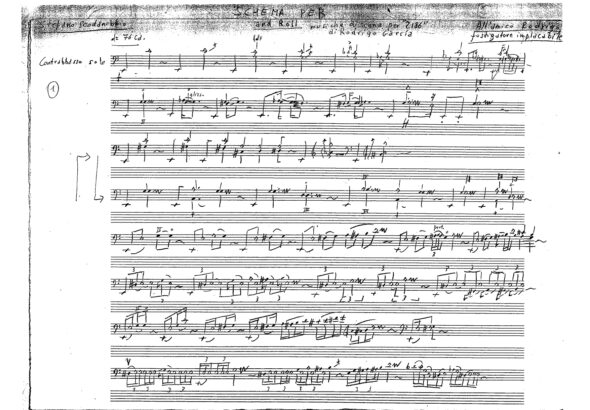

The idea of play is implicitly connected here. The composition suggests the inventive creation of syncopated motifs, with constant shifts in rhythm, in a kind of kaleidoscopic melodic pattern. The separate hand technique (upper system for the left hand, lower system for the right hand) is used to produce harmonics, which serve as the central material, in a manner akin to a drum or a metallic percussion instrument. Scodanibbio formalizes phrases in binary and simple and complex ternary meters, without repetition (3/8, 6/8, 13/16, 5/8, 4/8, 7/8, 8/8, 3/8). The strategy of this study is straightforward yet effective, enabling the creation of a percussive environment with intricate timbres. Moving toward the referential exoticism that frequently influences Western creation, the timbral orientation shifts to the sound of bells and metallic percussion. In many other compositions, this fluid environment of melodic and timbral movements, propelled by a sense of sequential gradation, can be perceived, as in & Roll (2007), where the material evolves over time.

An Extension of the Body and Musical Thought

In a text titled <<Una prolongación del cuerpo (el contrabajo)>>, published in Mexico in 1989, Stefano Scodanibbio and Gianfranco Leli share a reflection on the body-musical concept that deepens the understanding of the poetic ideas of their time.20 The starting point is an artistic approach that supports the idea that instrumental practice emerges from an exploration of the sound possibilities of the instrument, followed by the invention and development of a new technique grounded in theoretical awareness.21 This begins with two premises that make virtuosity the point of intersection between the performer and the composer. On one hand, the composer’s thought formalizes a mechanism in the score that pushes the performer to their limits. On the other hand, the performer’s virtuosity is understood not as a display of skill, but rather as “a tension to the limit, a pushing of human faculties, rediscovering, from a renewed perspective, the essence of the means, its true origin, the concept of ‘virtue.'”22

It is within this context that the importance of the performer in the creative process is reinforced, understanding the instrument as both a historical and symbolic condition, and at the same time, a fragment of the musical language (participating in its pragmatics and syntax)23. In this way, the double bass contributes with its specific resources: a broad harmonic body, a resonance surface, and infinite possibilities of range (very low notes and harmonics), offering opportunities for intervention in each of its parts. The idea of sensuality and the loving relationship between the body of the performer and that of the instrument is revisited, while not overlooking the fact that physical conditions demand specific attention to instrumental ergonomics: economy of movement, the valorization and preparation of attacks, and stillness during pauses or silences; conditions that allow for the establishment of, in the authors’ words, a “physiological contract” with the instrument.24

The text revisits the idea of the shaman, the magical being, the “magician.”25 The metaphor serves as an argument when questioning the existence of a commitment to the nature of the instrument, blending physiology and thought, sound and language in a balanced way. The achievement of the performer, in this sense, is to “enchant the listener,” making “a magical sense […] of enchantment emanate from the dialogue between performer and instrument, which no longer refers to virtuosity.”26 Through this concept, an appeal is made to the universe of primitivist poetics, where the double bass becomes a resonating chamber “of primordial distances, from the depths of cave vibrations, carrying a memory of gestures, dramatic and ritual behavior […]”27. Declared symbolic elements are framed within an exploration of what is called “instrumental theater,” likely referring to the “musical theater” device explored by composers since the late 1960s and which, to be precise, Luciano Berio (1925-2003) considered as a means to represent a non-aestheticized reality.28 It is in this dramatic exploration that the double bass (according to the words of Scodanibbio and Leli) finds its most complete form, due to its choreographic character, whose presence “captures, fascinates, and demands an unlimited attention to perceive the most faithful sound, to capture the smallest gesture.”29

This reflection on the body, both emancipatory and a source of theoretical contemplation, resonates in some of the poetics of our time. We can recall the research of composer Yann Robin (1974-), which is framed within the organization of saturated sound material, pushed to its technical and physical limits.30 This idea is further reinforced by what the double bassist Nicolas Crosse (1975-) has observed regarding the importance of the body’s engagement and the energy it projects—an element that, in his view, young composers often overlook when it comes to the double bass.31 We should also remember the concept of physicality that motivates composer Arthur Kampela (1960-) to explore the ergonomic relationship and the embodiment between the body and the instrument32—an approach that aligns with that of composer Samuel Cedillo (1981-), whose work embodies the idea of a score-device that allows the embodiment of sound action, to be projected as a mass toward the senses.33

Other Musical Traditions and Practices

It is impossible not to mention that the very idea of a Renaissance of Instrumental Music is fueled by an observation of other traditions and practices. The search for innovation through instrumental means involves the appropriation of resources from other creative sources, but not necessarily those that might seem the most obvious. The temptation to link Stefano Scodanibbio’s artistic work with figures such as Charles Mingus (1922–1979) or Jaco Pastorius (1951–1997) is strong, yet it does not appear that this is the way to understand the phenomenon of hybridization. It seems that the relationship is found in references more closely tied to the sonic culture of his time, which would have consequences in how the sound of the instrument itself is conceived.

There has been discussion of a possible connection between Scodanibbio and bass figures in practices such as jazz, particularly Charles Mingus (1922–1979), who died in the same region of Mexico where Scodanibbio chose to spend his final days.34 Beyond the anecdotal aspects and speculations described in these sources, it is certain that Scodanibbio mentions the American bassist on only one occasion in his memoirs. He does so in a brief entry in his diary, dated October 18, 2010, while in Cuernavaca, Mexico, just months before his death. In this text, Scodanibbio describes a beautiful environment around him, but a dark internal atmosphere, likely due to his severe health condition:

“The first two weeks in Mexico were filled with the usual dark thoughts, a few anxieties mostly caused by Maresa’s instability, many enchantments in the Garden, undoubtedly due to the Gabapentin but also to the “Mexican time.” I like this house, a bit as I imagined it: fascinating, old, full of colors, and also with beautiful paintings by Jody, the luminous studio, the shadowy room, the garden that is a living Douanier. How about Mingus?” 35

In fact, the clue to understanding the connection between Scodanibbio and other musical traditions lies on a broader level of sonic culture:

“On the other hand, I cannot completely ignore what has happened in this century, not only musically... as if nothing had occurred on the staff between Brahms and Ferneyhough. I cannot continue thinking as if jazz had never existed, as if Hindu music had not reached our concert halls, as if rock had not bombarded everyone’s ears in public spaces. I cannot continue ignoring the fundamental contributions that certain artists, outside of “European” classical music, have made. I think of the importance, for the evolution of the guitar, of a musician like Jimi Hendrix, or of that of Jaco Pastorius for the evolution of the bass. I cannot think of the voice without thinking of João Gilberto or the great jazz singers. I think of Ram Narayan as one of the great living musicians, possessing an extraordinary bowing technique. I think of how it came to be that the sarangi, an accompanying instrument of Northern India, was transformed into a solo instrument that sings like the cello, or sometimes even better.

All of these, and many others, are part of my sonic universe, before it is musical.”36

The categorical statement that concludes this fragment allows us to understand that the greatest influence of these practices lies in the sonic culture of the present. In this same sense, we should recall the pedagogical perspective of oral tradition practices, as testified by the composer Fausto Romitelli (1963-2004) regarding his sonic environment. It is not just an interest in the universe of amplified devices of his time (radio, television, etc.), but rather an assimilation of the practices of musicians like Jimi Hendrix and Aphex Twin; from which Romitelli extracts the lesson of an electroacoustic sound exploration and the idea of sonic processes and interferences.37

Among the possible references, two stand out due to their connection with oral tradition practices. The first strategy is based on instrumental exploration through improvisation, with electroacoustic sound at its core. In & Roll (2007), a solo double bass piece composed in the context of music intended for theater38, the reference to Foxy Lady (1967) by Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970) allows Scodanibbio to explore instrumental sound in two main directions. On one hand, it anticipates the idea of imitating electroacoustic sound, particularly that of the electric guitar with distortion effects, through an acoustic means. This result is achieved by emphasizing the spectrum of fundamental frequencies through the strategic use of the bow (bow positioning, dissonant intervals on simultaneous strings, percussive attacks with the ivory tip of the bow, etc.) and by preparing the instrument to generate sound-noise similar to electric material. These strategies strengthen the approach to improvisation through processes of gradual transformation of sound, based on the repetition of the characteristic riff of the song. Another example of this operation can be heard in “Voyage Started” and “Voyage Continued,” the first and third movements of Voyage that never ends (1979-1997).

As for the second strategy, it involves the exploration of modular repetition according to the principles of improvisation mentioned above. In & Roll, instrumental virtuosity traces a path that combines technical exercise with instrumental sound exploration in situ39. In other words, the performer becomes the creator of the emerging sound material, triggering a continuous cycle between sound production, listening, and repetition. This process constantly regenerates, giving rise to a musical form without rigid prescriptions, characterized by fluidity and flexibility, and leading to the invention of a new instrumental language.40

An emblematic reference could be Jimi Hendrix’s concert in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1969, particularly during his performance of Sunshine Of Your Love (1967). Around the central riff, Hendrix explores various timbral qualities of the guitar, intervening on the pickup, manipulating the potentiometers to filter the sound, and employing techniques ranging from the use of the pick to direct percussion on the strings. Scodanibbio’s connection to the practices of oral tradition lies precisely in this exploration, free from any predetermined calculation, through improvisation processes and the use of modular variations.

- 1. Stefano Scodanibbio, Giorgio Agamben et Maresa Scodanibbio, « Sul Rinascimento strumentale », in Non abbastanza per me: scritti e taccuini, Macerata : Quodlibet, 2019 (In ottavo, 29), p. 34‑38. ↩︎

- 2. Bañuelos, op. cit. (nota). ↩︎

- 3. Estrada, op. cit. (nota), p. 29. ↩︎

- 4. Scodanibbio et al., op. cit. (nota), p. 35. ↩︎

- 5. Ibid. ↩︎

- 6. Ibid. ↩︎

- 7. Ibid. ↩︎

- 8. Ibid., p. 38. ↩︎

- 9. Testimony from Helmut Lachenmann in 2019, during a composition masterclass in Tel Aviv, Israel. In it, he recounts how Nono considered the trill a technique inherently “bourgeois.” ↩︎

- 10. Grazia Gracco, « Salvatore Sciarrino : vers une écologie de l’écoute », in Théories de la composition au XXe siècle, Paris, France : Symétrie, 2013 (vol. 2/2), p. 1716. ↩︎

- 11. Ibid., p. 1717. ↩︎

- 12. Ibid., p. 1719. ↩︎

- 13. Ibid., p. 1726. ↩︎

- 14. Storia della musica, third edition, Torino : Giulio Einaudi editore, 2019 (Piccola biblioteca Einaudi), p. 159. ↩︎

- 15. Maurizio Pisati, Intervista a Maurizio Pisati: l’opera per chitarra di Stefano Scodanibbio, 2023, Questionnaire. ↩︎

- 16. Ibid. ↩︎

- 17. Seth Josel et Ming Tsao (dir.), The techniques of guitar playing, Kassel Basel : Bärenreiter, 2014, p. 108‑109. ↩︎

- 18. Magnus Andersson, Intervista a Magnus Andersson: l’opera per chitarra di Stefano Scodanibbio, 2023, Questionnaire. ↩︎

- 19. Stefano Scodanibbio, Sei Studi, Manuscript (copia), 1983. ↩︎

- 20. Stefano Scodanibbio et Gianfranco Leli, « Una prolongación del cuerpo (el contrabajo) », in Nuevas Técnicas Instrumentales: flauta, oboe, clarinete, arpa, cuerdas, contrabajo, guitarra, translated da Magolo Cárdenas, México : Conaculta, INBA, Cenidim, 1989, p. 112‑114. ↩︎

- 21. Ibid., p. 112. ↩︎

- 22. Ibid., p. 112‑113. ↩︎

- 23. Ibid., p. 113. ↩︎

- 24. Ibid., p. 114. ↩︎

- 25. Ibid. ↩︎

- 26. Ibid. ↩︎

- 27. Ibid. ↩︎

- 28. Luciano Berio, Angela Ida De Benedictis e Giorgio Pestelli, « Problemi di teatro musicale », in Scritti sulla musica, Torino : Einaudi, 2013 (Piccola biblioteca Einaudi, N.S., 608), p. 42‑49. ↩︎

- 29. Scodanibbio et Leli, op. cit. (nota), p. 114 ↩︎

- 30. Jéremie Szpirglas, « Entretien avec Yann Robin et Nicolas Crosse », Ensemble intercontemporain, 2/11/2014.URL:https://www.ensembleintercontemporain.com/fr/2014/11/entretien-avec-yann-robin-et-nicolas-crosse/ Accessed September 6, 2024. ↩︎

- 31. Testimony from a meeting with the double bassist in Paris, 02/04/24 ↩︎

- 32. Arthur Kampela, Arthur Kampela : Lenguajes modernos de la guitarra II, Videoconferenza presentata da Arthur Kampela : Lenguajes modernos de la guitarra II, Università di Guanajuato, 10/06/2020 URL : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hw-CNRwH5dY. Accessed August 5, 2024 ↩︎

- 33. ván Adriano Zetina, Prologue à Machine Parlante : notes sur la création musicale mexicaine, Conferenza pre-concerto Machine Parlante e, Grand Salon, Fondation Satsuma- Maison du Japon, CIUP, Paris, France, October 11, 2019. ↩︎

- 34. Paolo Gironimo di, « Mingus y Scodanibbio: los dos volcanes del contrabajo », PiLacremus: perspectiva interdisciplinaria del laboratorio de creación musical, translated da Julio Estrada, 2016, p. 15‑23. ↩︎

- 35. Scodanibbio et al., op. cit. (nota), p. 263. ↩︎

- 36. Ibid., p. 36. ↩︎

- 37. Eric Denut, « Produire un écart : entretien avec Fausto Romitelli », en Musiques actuelles, musique savante : quelles interactions ?, Paris, France : L’Harmattan : L’Itinéraire, 2003, p. 74. ↩︎

- 38. Stefano Scodanibbio, Giorgio Agamben et Maresa Scodanibbio, Non abbastanza per me: scritti e taccuini, Macerata : Quodlibet, 2019 (In ottavo, 29), p. 292. ↩︎

- 39. Stefano Scodanibbio: & Roll (2007), 9:10, [s.l.] : [s.n.], 2010. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFQj1AR2YP4. Accessed May 3, 2024. ↩︎

- 40. Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E7LCiaixhtI. In this fragment, we can appreciate the way Scodanibbio moves between improvisation and composition, sound production and listening, material creation and its formalization, thus redirecting the idea of instrumental virtuosity. The structure of & Roll, which serves as a score, confirms the pendular movement between determination and freedom in musical writing. ↩︎