Editor’s Note: With this interview, we inaugurate a new section on our website: GuitarOFF.

As the title suggests, it will be dedicated to personalities and themes in contemporary music, but beyond the world of the guitar.

After this brief introduction, we leave you to the interview with Stanislas Pili and Spielplan by Mauricio Kagel.

Mauricio Kagel (1931-2008) was one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. His works explored crucial themes for the evolution of musical and theatrical practice through sound research, the use of unusual objects and a unique scenic writing style. Kagel often challenged avant-garde conventions, maintaining a constant tension between the absurd and the everyday. Among his most notable compositions is Staatstheater (1967-1970), a monumental work that defies the very concept of musical theater. The sixth book, Spielplan – Instrumentalmusik in Aktion, consists of 42 graphic pages that require the use of prepared and amplified objects and allow for a “concertante” version.

Stanislas Pili, João Calado and Andrea Zamengo devoted months studying and interpreting this work, presenting a first version in Basel at the Gare du Nord-Bahnhof für Neue Musik on May 21, 2024. On the occasion of this debut, we interviewed Stanislas Pili for Guitar Off to delve into the unique aspects of this ambitious project.

Stanislas, thank you for accepting our interview proposal. Where did the idea for this project originate?

In recent years, I have mainly focused on creating pieces and performances of my own composition, but I also wanted to return to work as a performer, searching for something in the repertoire that had not yet been thoroughly explored. By consulting the seven volumes freely available to realize the Staatstheater spectacle, I noticed that Spielplan is explicitly written for percussionists and can be performed autonomously, without integrating it into a theatrical staging.

I found various artistic productions dedicated to Staatstheater in written and online archives where some pages of Spielplan had been included. However, I did not come across any information regarding an excecution of Spielplan in an independent version, so it is likely that no one has never realised this possiblity or, at least, documented it. Perhaps a concertante version of Spielplan has never been considered because it was overshadowed by the theatrical and visual focus of Staatstheater, which caused stir at the time.

Instead, Repertoire (1970), the first volume of Staatstheater, it was often performed autonomously by both Kagel and other international artists. Acustica – for experimental sound generators (also from 1970), written in a very similar way to Spielplan, was also performed and documented several times.

However, Kagel believed in this possible interpretation of Spielplan. At the Paul Sacher Stiftung archives in Basel, I read an early version of the score, printed as a test by Universal Editions, where, strangely, the phrase indicating the possibility of a concert version does not appear. Kagel had corrected the rules page of the piece, adding the idea of an independent version, which is still present in the score today.

One of the reasons that convinced us to reconstruct Spielplan is the vast array of sounds it proposes, considering that the piece is over 50 years old. Simply browsing through the book pages reveals an astonishing number of experimental ideas and techniques illustrated by Kagel. My friends João Calado and Andrea Zamengo, also interested in sound experimentation, were immediately motivated to embark on this adventure together.

Even though the rules allow for a selection of pages, we decided to play the piece in its entirety. Our mission was to explore the proposed sound materials as deeply as possible, isolating them from theatrical and scenic elements that could influence the listening experience and structural arrangement.

In the book, Kagel specifies that each gesture must be performed only once during the performance. This entails a continuous change of positions and scenes, requiring performers to adhere to precise rules. What were the main challenges you encountered, and how did you address each interpretative choice?

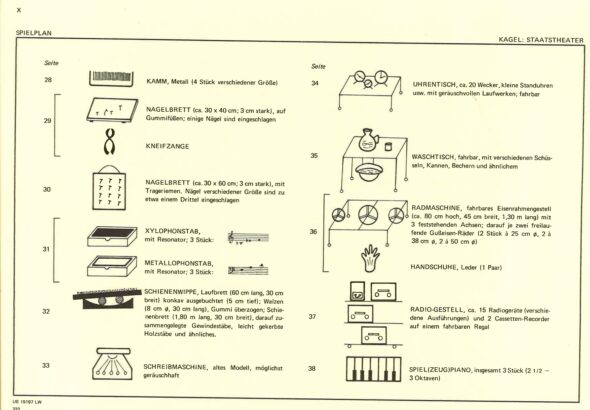

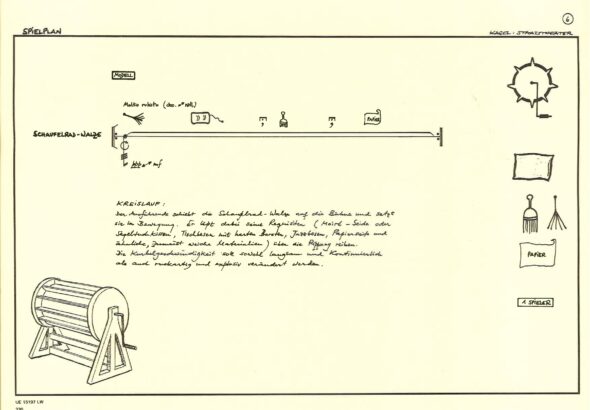

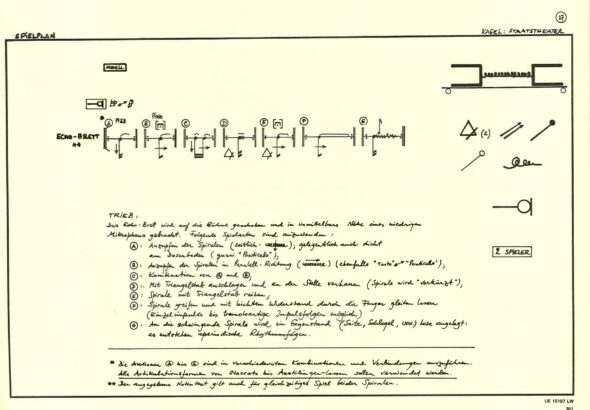

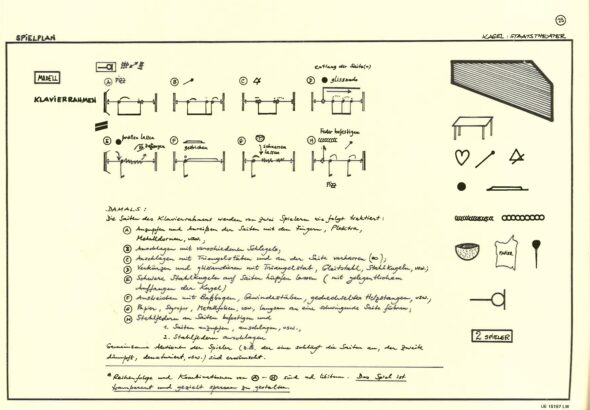

In the introduction, a long catalog (Instrumentarium) describes the materials and objects (sound generators) to be used. Each of the 42 graphic pages of the score focuses on one sound generator and offers:

- A drawing representing the instrument to be played.

- Performative and sonic possibilities explained through handwritten phrases.

- Short musical excerpts, written on staves and called Modell, provide examples of how to play the instruments.

The order of the pages and the duration of each sound action is free. However, as you mentioned, a page cannot be repeated once completed. Additionally, the various pages can overlap, but a performer can only play one page at a time.

Unlike some works by John Cage, where chance creates the structure (aleatory systems, the use of I Ching, etc.), Kagel specifies in the pages of Spielplan that everything must be determined precisely during rehearsals and the material must be used sparingly to keep the musical interest and, consequently, the audience’s attention high. Therefore, Kagel not only allows the performers to create their own version but also places significant responsibility on them as arrangers.

It was an enticing challenge for us to combine the executive aspect with the creative one. In addition to learning how to play the various materials appropriately, we had to determine a clear structure without repetitions, avoiding the piece sounding like a mere catalog and maintaining musical tension from the beginning to the end of the concert.

Here some structural solutions we adopted in our 50 minutes version include:

- Certain pages are played simultaneously (each performer plays one) for several minutes, creating musical scenes conceived as movements that segment the concert.

- In other cases, all the performers play the same page together. For example, page 23, Klavierrahmen (piano frame), constitutes a micro-piece within the concert.

- Other pages are short and are used as transitional elements between longer musical sections.

The pages of Spielplan require a very specific sound exploration through the use of prepared instruments, modified objects, and amplified sounds. Which sounds impressed you the most during your exploration, and which characterized your performance choices?

As soon as we began working, we confirmed that, behind the 42 drawings and the few handwritten explanations left by Kagel, lay an extremely vast sound universe to explore.

Rediscovering the sounds of Spielplan was not only the most enjoyable phase but also the most decisive one, as it influenced our final arrangement choices. For example, we noticed that some pages worked well when played in parallel because they generated similar sounds or, conversely, offered contrasting elements that acted as counterpoints to other materials.

We wanted to explore all the sonic possibilities of the work, especially taking advantage of the fact that Kagel suggests to use a close-up microphonation. After collecting and assembling the various materials, we tested one instrument at a time, monitoring the sounds through headphones (never acoustically) to evaluate all possibilities based on microphone placement. Thus, in addition to trying the various sound effects an object could produce, we tested which microphone to use and where to place it to capture the most intriguing sounds.

Producing sounds using a “strange” instrument proposed by Kagel was not enough; it was necessary to explore all the performance opportunities, nuances, preparations and possible timbres of the sound generators he had designed, just as it has been done at the academic level with conventional instruments.

Was there a moment during the performance when you felt the need to emphasize a gesture to help the audience better understand the sound source? Or did you prefer to surprise the audience, letting them discover where certain sounds came from on their own?

Kagel explains that every action must be “transparent”, a performer plays only one instrument at a time, so the audience can easily identify the various sound sources on stage. Additionally, in our version of the piece, we did not include pre-recorded tapes (although Kagel allows them), except for brief moments when the performers activate noises using cassette players on stage. Therefore, every sound is produced live and each gesture corresponds to a sound.

Our conversation highlights the importance of sound. How did you collaborate with audio engineer Maxime Le Saux to achieve specific results?

For the Spielplan project, we worked with Maxime during the final phase, during rehearsals at the Gare du Nord. As mentioned earlier, we always studied Spielplan using microphones, immediately developing a clear sound design concept for the piece. However, before being able to set up all the instruments at the Gare du Nord, we worked in a small room without using loudspeakers to listen to ourselves, so we had to work with headphones. Maxime’s challenge was to balance the sounds at the Gare du Nord as we had heard them in our headphones. This was not always simple because some instruments sounded hyper-amplified in headphones but lost sonic mass in the hall (for example, rhythmic sounds produced by a water dripper installation) and in other cases, certain frequencies were too prominent in the hall. It is worth noting that some microphones were placed inside tubes; in headphones, the sound was fantastic, but in the hall, feedbacks occurred and the volume gain was too limited compared to other instruments.

Thus, Maxime not only managed the live mix during the concert but also had to find the right solutions during the sound check to transpose the sound design we had created during the study phase to the Gare du Nord.

During the arrangement process, were there gestures indicated in Spielplan you had to sacrifice to maintain the overall balance of the performance?

Rather than sacrifices, I would speak of compromises, especially in terms of instrumentation. For this project, we had to do a philological work to find the necessary components to recreate the piece. Kagel had at his disposal both objects found in the fundus of the Hamburg Staatsoper (where the premiere of Staatstheater took place) and other personal materials, which were not always easy for us to find in identical versions on the market.

In some cases, we reworked certain information provided in the score to ensure effective sound results, solve transport issues, manage stage space and accomplish everything within the available budget.

In the Staatstheater staging, as in a carousel, instruments and performers can enter and exit the stage. In that context, the instruments, even if used to produce sound, also acquire a scenographic and sometimes caricatured function. But we focused on a concertante version of Spielplan where the all instrumentation remains fixed on stage. Consequently, our choice of materials was always made based on sound quality rather than visual appearance. When analyzing Kagel’s descriptions, we always asked ourselves how an instrument should sound rather than how it should look.

For example, the score proposes a giant bass drum with a shell 2,50 m in length and 1,60 meters in diameter, prepared with cables coming out of the drumhead (also used in Saison, the fifth book of Staatstheater). It was difficult for us to build and it took up a lot of space on the stage. For this version at the Gare du Nord, it was replaced with a smaller drum, inside which we placed a microphone and worked extensively on bass equalization, thus sacrificing the scenographic aspect but not the sound effect. Another example: long PVC pipes are required; we opted for a pool plumbing pipe because it produces many more harmonics and can be rolled up for transport.

In other cases, we enlarged the instruments for sound reasons: for instance, Kagel suggests connecting tin containers with springs, but after several attempts, we chose to mount the springs on drum-set toms and finally amplify the sound with contact microphones placed on the drumheads. This solution allowed us to achieve longer reverberations and deeper bass.

In other pages, we were extremely faithful: Kagel requires the metal frame of a grand piano, which is difficult to obtain because, in addition to having access to a piano, you must be able to disassemble the wooden case, completely dismantling the instrument. Luckily, Andrea owned a grand piano that had already been disassembled for another project.

In the category of traditional instruments, a wind machine is required, from which the top cloth must be removed to apply preparations on its wooden blades. A wind machine is an instrument available only in opera theaters and has a very high cost. In this case, it was more convenient for us to buy the wood and build a new wind machine specifically for the project.

This research on the experimental sound generators proposed by Kagel is an ongoing work in progress that can evolve in the future.

Kagel was a central figure in avant-garde music and theater. In your opinion, what remains of his work in contemporary musical theater today?

In my opinion, Kagel was one of the pioneers of the “cross-media” composer figure, dedicated to create music in combination with visual and scenic elements of all kinds. He always wanted to experiment with new ideas taking advantage of all available media, at a time when technology was not as accessible as it is today. We can find a “transmedial” approach (sound, video, performance, staging) in the work of prominent contemporary composers (Simon Steen-Andersen, Brigitta Münterdorf, Alexander Schubert, Jennifer Walshe and Heiner Goebbels, to name a few) as well as among young artists of the latest generation.

Let us also remember that Kagel, in addition to his production of chamber and orchestral works, created radio plays (Hörspiel) and experimental films in which he explored the relationships between sound and image.

He was certainly among the first to include multimedia elements in a single score, treating them musically and in a non-hierarchical way. One example is Camera Oscura from 1965, written for spatialized sound tapes, three performers moving on a cyclorama, three performers controlling rotating video projectors and three performers managing spotlights.

In his works of music theater, or as he defined it, instrumental theater, he combined sound action with gestural, scenic, and vocal events. In these experiences, he often included humorous, parodic, or self-referential moments, elements that, although developed differently, are present in some current music theater creations.

In addition to directing and staging his own works, he was often one of the performers on stage, anticipating the current figure of the composer-performer. This aspect is also developed in works such as Staatstheater, where the performers must work on their arrangement of the piece.

Kagel, with his eclectic state of mind, did not crystallize around a single artistic attitude or language. I believe that a synthesis of this “kaleidoscopic” approach also exists in his scores, where he explores writing techniques become fundamental to current musical production. In fact, in addition to using rigorous conventional notation, he also integrated drawings, rules reminiscent of role-playing games, graphic elements and actions described in words on a vertical table (for example, Sur scène from 1960). Sometimes, these different writing methods mix within the same piece, such as in Transition II from 1959 (for a pianist, a percussionist playing the piano strings and audio tapes) and in Spielplan itself, where three levels of writing (conventional, graphic and descriptive) coexist on each page of the book.Although Kagel is mainly cited for music theater, I find that one of the most surprising and still highly relevant aspects of his work is his sound and timbral research. In addition to working with electronics from the beginning of his career, he was an innovator in the idea of developing new musical instruments, expanding or transfiguring conventional ones and exploring new performance techniques. Kagel included instructions for creating analog sound devices, often self-built and realized with a DIY approach. But not only that, he was interested in extra-European musical traditions (Exotica from 1971) and even in reusing ancient instruments (Musik für Renaissance-Instrumente from 1966).

Finally, what fascinates me in pieces like Spielplan is that Kagel does not limit himself to making prepared instruments or, alternatively, ready-made noise-producing objects but goes further by proposing the preparation of the object itself, an approach currently developed by contemporary composers such as Michael Maierhof.

After the presentation at the Gare du Nord, do you plan to continue with this project?

Certainly! We are organizing concerts for 2025 and 2026 in both Switzerland and Europe. In parallel, we are working on an album, an essential step to complete our work on Spielplan.