In 1977, Helmut Friedrich Lachenmann presented his work Salut für Caudwell for two guitars for the first time in Baden-Baden, with the performance entrusted to Wilhelm Bruck and Teodor Ross. Although Salut für Caudwell is not Lachenmann’s first composition for guitar, it is the first entirely dedicated to this instrument, simultaneously marking a true turning point in its history.1

This work not only holds significant importance in the development of the guitar but also serves as a clear example of the composer’s aesthetic evolution, as well as his musical, philosophical, and political thought.

Using Salut für Caudwell as a representative piece—allowing a deeper exploration without reducing the article to a mere analysis of this single work—three fundamental aspects of Lachenmann’s music will be examined: the aesthetic-sonic dimension, the conceptual-aesthetic considerations of this period, and the political dimension in his work.

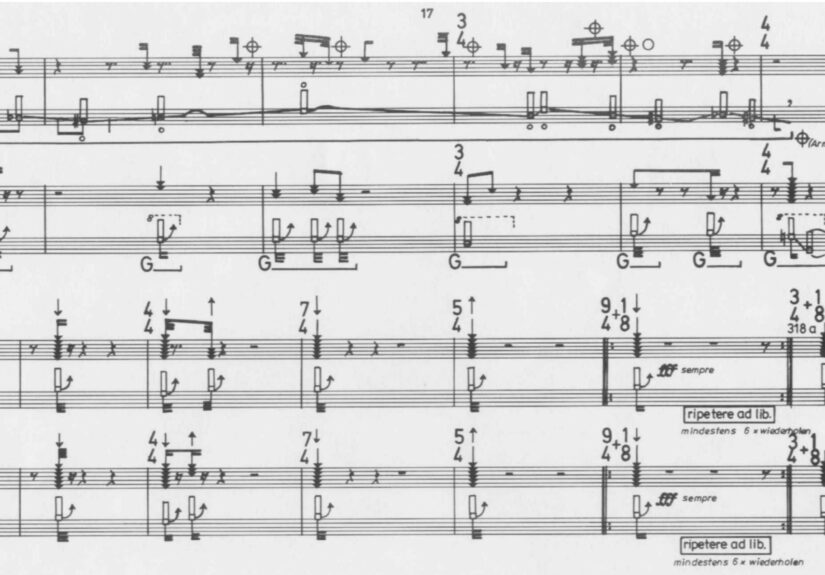

The first thing encountered when opening the score of Salut für Caudwell is a detailed legend with precise performance instructions. These include techniques never previously used, multiple notational forms, and a structural layout that was innovative for its time. In other words, the performers’ first task is to familiarize themselves with techniques and a method of notation uncommon in traditional guitar pedagogy. Added to this is a non-transposing2 score and scordatura (all strings of the second guitar must be tuned half a tone lower than standard tuning).

All of this reflects the aesthetic-sonic exploration developed by Lachenmann, particularly in the late 1960s and early 1970s with works such as Pression (1969-70) for solo cello and Kontrakadenz (1970-71) for large orchestra, an approach that would continue evolving throughout his career. Lachenmann succeeded in transcending the abstract structuralism of the 1950s and the sonic empiricism of the 1960s, synthesizing both through the mutual interpretation of the structural aspect of sound and the sonic aspect of structure.3

His work would focus on exploring the essential characteristics of sound production and the energy required for it, resulting in what he himself defines as “instrumental concrete music.”4

The goal of this exploration, derived from the artistic-social context of the time, is to subvert bourgeois listening habits, as well as to “liberate listening” from all internalized expectations.5

As the composer will write in Hören ist wehrlos – ohne Hören:

“Listening – to which too much is demanded and at the same time too little in an era of musical abundance – must liberate itself by entering into the structure of what must be listened to, acting as a perception consciously set in motion, an evident, provoked perception.“6

Listening must not only enter into the structure of what needs to be heard, but it must go further, marking realities and possibilities situated around us and within us. This will lead Lachenmann, not only to a deep revision of the fundamental aspects of sound production, but also to a reconsideration of the relationship between performer and instrument.

In this regard, in his text Über das Komponieren (1986), Lachenmann states that “composing means building an instrument.”7

In other words, the composer adapts the instrument to his sonic intentions, treating it as a “sonic body” rather than according to traditional interpretive standards. For Lachenmann, composing means “experimenting with something” rather than “saying something.”

The construction of a new instrument is not only the concern of the composer, but the performer must actively participate in the process by re-learning the technicalities of the instrument or, as in the case of Salut für Caudwell, adapting their technique to a new interpretive and sonic reality. Beyond the composer and performers, the audience completes the circle of the work, as they too must learn new listening codes and reconsider the ones they already know. As Luigi Nono, Lachenmann’s mentor, would say, “The ideal listening would not be the one that escapes all conditioning, but the one that can point out and bring to light what conditions us in order to question it and search for other possibilities.”8

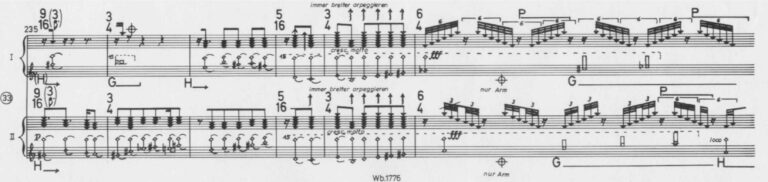

Returning to Salut für Caudwell, as mentioned, the performers will need to adapt their technique to a new interpretive reality. For example, in the introductory section (measures 1-23), the right hand of both guitarists primarily performs plucked sounds with a pick, while the left hand executes Barré stops, both with the fingers and a bottleneck. Up to this point, the performers are in a “technically familiar” territory, yet in other aspects they must adapt to a new reality. The first innovation is a score divided into two systems associated with the right and left hands, with the first serving as tablature for the six strings, also indicating rhythmic and dynamic aspects, while the second is used exclusively for fingering notation.

On the other hand, the performers must be very aware of all the subtle sonic changes that each detail of the score implies: variations in pressure in the left-hand fingerings, the use of the bottleneck as an element for fingering instead of the fingers, changes in the right-hand contact point, and its use to dampen the resonance of the strings, and so on. In addition to all of this, the left hand of both guitarists moves in areas that are unfamiliar in traditional interpretation, adding another layer to the adaptation required.9

It is very important to emphasize that Lachenmann’s writing does not show the sonic result as traditional musical notation does, but rather what is written represents the physical gestures that the performers must execute to achieve a sonic result that cannot be anticipated without their experimentation.

Although graphic notation was not new at the time, Lachenmann takes it into a conceptually and sonically different territory. Until that moment, scores created with graphic symbols or those distanced from traditional notation (such as those by Cage, Feldman, Kagel, etc.) tended to lean more towards performance or musical theater than towards the Western tradition.

In Lachenmann’s work, the issue of notation returns to being a direct consequence of his exploration of the essential characteristics of sound production. However, in Salut für Caudwell, we can observe an evolution compared to earlier compositions, whose starting point was the energy and technique of sound production. Although this aspect remains a fundamental principle, Salut also proposes a reinterpretation of certain elements of the guitar’s sonic tradition, which appear in the piece as “ruin” or “shadow” within the overall sonic result. As the composer himself states, it is about: “eliminating the linguistic context of a familiar musical material and establishing connections through a renewed order of its elements.”10

Lachenmann had already developed this concept in some earlier works, such as Accanto (1976) for clarinet and orchestra (also featuring an electric guitar part), where he uses elements that could be interpreted as reminiscences of the Mozartian style found in the clarinet concerto K. 622.

In Salut für Caudwell, Lachenmann creates a series of sonic gestures that aim to connect not only with the tradition of the classical guitar but also with its use in folklore, rock, and even with geographical and cultural connotations.

An example of this connection to classical repertoire can be found in measures 239-240. Although in these measures the pitches are not defined in the sonic result, Lachenmann presents a certain reminiscence of the compositional tradition for guitar, such as in the Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 99 by Castelnuovo-Tedesco. In this moment, both guitars perform a continuo of arpeggiated elements, where the timbre varies depending on whether the left hand applies a light pressure on the strings without reaching the pressure of the harmonic (Lachenmann describes it as a “muffled” sound); whether the strings are fingered with the fingers or with the bottleneck; whether the contact area of the right hand is on the sound hole or on the bridge; or whether the resonance of the strings is muted or not.

The result has nothing to do with and cannot be directly associated with the neoclassicism practiced by Castelnuovo-Tedesco. However, if the listener is familiar with the guitar writing tradition, they may perceive a reminiscence of the Italian composer’s style in that arpeggiated character, within a kaleidoscopic and captivating moment, which is, in reality, closer to the acousmatic.

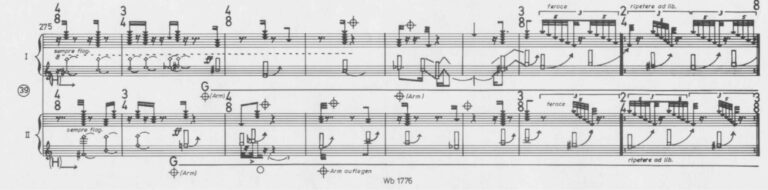

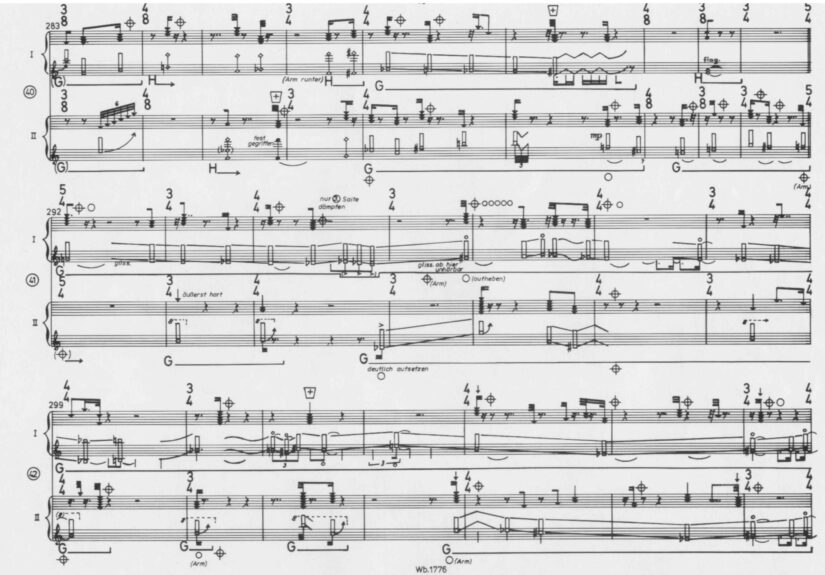

A conceptually similar moment, but with a distinctly different sound, can be appreciated in measures 281-282. Both guitarists’ right hands perform exactly the same descending arpeggio gesture as described earlier, but the left hands of both players execute an ascending slide of the bottleneck across all the strings, starting from a marked position. The result is a sort of crossed glissando, as the descending movement of the right hand causes the pitches to become progressively lower, while the ascent of the left hand produces exactly the opposite effect.

This interaction between the two hands creates a rich and intricate soundscape, blending the contrasting motion of both hands into a single, unified sonic experience. The timbral complexity introduced by the bottleneck sliding across the strings adds to the layered texture, allowing for a deep exploration of sound that challenges the listener’s expectations.

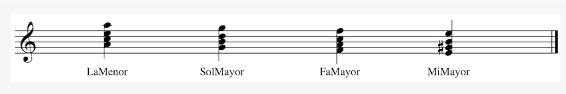

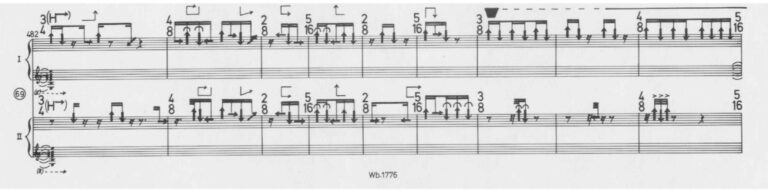

In Salut für Caudwell, as mentioned earlier, there are also connections with repertoires far from Western classical music. One example can be found in the final section (from bb. 465 to the end). In this fragment, both guitarists must rub the strings with the palm of their hand in a quick gesture, following the direction indicated by arrows in the score, even forming geometric figures with their movements. Once again, the experienced listener might detect very subtle reminiscences of flamenco in the harmony used and the rhythmic nature of the gestures.

On one hand, both guitarists’ left hands alternate between playing a standard A minor chord and an E major chord throughout the passage (it is important to remember that the second guitarist is tuned a semitone lower than usual). Therefore, as the right hand performs the rubbing gestures, the listener may sense a faint shadow of something familiar: the IV degree and tonic chords of the Phrygian cadence in flamenco harmony. This cadence consists of the descending steps of the first four degrees of the E Phrygian scale (derived from the Greek mode), with the third of the final chord altered in an ascending motion.

This subtle connection to flamenco further enhances the multi-layered sonic landscape of Lachenmann’s work, where traditional forms are reinterpreted and integrated into a new, experimental context, blending them with his unique exploration of sound and gesture.

However, by using only these two chords, the passage remains deliberately ambiguous, leaving room for interpretation. It could indeed be seen as a reference to the key of A minor (V-I), which is frequently discussed in Lachenmann’s writings. The final result of this passage is further distorted by the difference in tuning between the two guitars, creating a tension in the sound that makes the tonality blurred and not easily recognizable.

From a rhythmic perspective, the gestures of the right hand reflect the accentuation subdivisions typical of flamenco palos. These palos, which are usually built on twelve pulses, are accentuated in groups of two and three (or more), depending on the type of palo. Lachenmann reinterprets this rhythmic idea in the figures he writes in this passage, always aware that it is a reinterpretation within a completely different sonic reality from the flamenco tradition.

Additionally, in measure 490 (second guitar), there is a gesture that recalls the typical rasgueo of flamenco guitarists, further demonstrating how Lachenmann incorporates elements from distant musical languages but transforms them and places them within an entirely original and experimental sonic context.

Similarly to the conceptual evolution observed in the motivic-sonic treatment of the piece, one could speak of a structural continuity in Lachenmann’s work in relation to his previous compositions. The structural organization could be understood as a thought derived from John Cage’s idea of the “empty container,” as well as from the exploitation of motifs from the music of German composers, especially starting with Beethoven.

From the very beginning of his career, critics have drawn comparisons between Lachenmann and John Cage in terms of structure. Despite efforts to distance himself from the American composer, sometimes through heated debates, the Stuttgart composer recently admitted that he truly has a “deep influence” from Cage.11

This idea of the “empty container” involves the preliminary fragmentation (regular or irregular) of a temporal space into sections that will be filled (or not) with sounds. This fragmentation could derive from mathematical elements, nature, or even chance. In Salut, Lachenmann carries out a division of the structure where, clearly, different sound objects will dominate depending on the section, or, in Lachenmann’s terms, the structure will consist of “a polyphony of ordered juxtapositions.”12

There is no clear process that leads us from one moment to the next, nor is there an apparent sonic connection between adjacent parts, except in some transitions with overlapping elements. That is, each sound object, or group of sound objects, has its own vital space where it is born, develops, and dies, although the same elements may be reused later. A brief motivic-structural association would be the following:

- Introduction (1-27): Almost like an opera prelude, it presents most of the sound objects that will be developed throughout the piece.

- Section A (28-178): Fragmented into two parts, the first focuses on sounds derived from the plucking of strings with a pick. The second continues with the same sounds but adds the vocal part of the piece.

- Transition (179-207): A moment of ethereal sounds in which secondary sound objects of the work are used.

- Section B (208-360): Fragmented into three parts, the main element is again the string plucking with a pick. The first part bears similarities to Section A; the second introduces the use of the bottleneck as a digitating element, as well as the introduction of sliding glissandi with it; the third involves a substantial lowering of the dynamics and focuses on resonating sounds supported by the movements of the bottleneck in the left hand.

- Section C (361-464): Also fragmented into three parts, the first focuses on sounds obtained with the bottleneck, either through a whammy-bar-like vibrato, slides, or tremolos. The right hand only produces sounds of scraping the strings with the fingernail or dampening their resonance. In the second fragmentation, the bottleneck is used as a percussive element against the strings. The right hand continues similarly. Finally, in the third, the bottleneck moves to the right hand and continues to act as a percussive element, while the left hand now focuses on digitating.

- Final Section (465 to end): Focused on the string-friction gestures described earlier.

As seen, each gesture has its own space and is rarely combined with others, except in particular occasions. Despite this structuralism, Lachenmann utilizes many resources that could be associated with the German compositional tradition, for instance:

- The sonic gestures evolve throughout their respective sections and mark their subtle directionality.

- He uses recurring sonic elements as connections between distant sections.

- In some cases, the change from one section to another is not abrupt (with silence), but the subsequent sonic material is briefly anticipated or, conversely, the previous sonority is slightly maintained during the section change. This creates an intermediate blending that connects the sections.

- At certain moments, Lachenmann uses classical techniques of accumulation or dissolution of sonic elements to increase or reduce the tension of a section.

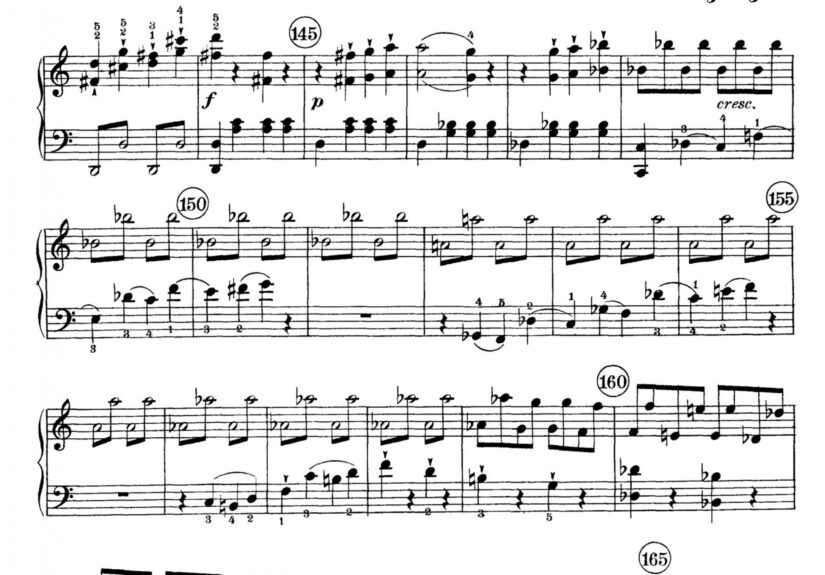

If we take a brief comparative example between the second fragmentation of Section B (measures 283-312) and the development of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 8 Op. 13 (measures 136-193), we can observe subtle similarities based on the ideas discussed above.

In this section of Salut, Lachenmann uses the element of string plucking with a pick as the primary and sole element, along with the bottleneck as a digitating tool. With this single basic element, he builds the entire fragment. Beethoven, in his development, constructs the section using the theme A motif from the exposition as the primary and sole element.

In Lachenmann’s case, the gesture evolves in timbre depending on how the sound is produced, but the technical basis of the gesture remains unchanged: at the start, the left hand uses the fingers to pluck the strings; it then switches to using the bottleneck in a static position on the second guitar and sliding on the first guitar; both proceed with subsequent slides, with the second guitarist finishing with an energetic upward slide that will connect to the third fragmentation. The right hand remains unchanged throughout the passage, with some changes in the plucking area and the work of damping and releasing resonance. An entire timbral evolution based on the same basic motivic element.

In Beethoven, the same motif also changes sonically, but in this case, it is associated with harmonic, register, and articulation factors.

As mentioned, Lachenmann uses the energetic sliding element (measures 311-318) as a connecting element between the fragmentations, at the end of the second and at the beginning of the third. Beethoven uses the dominant pedal to harmonically anticipate the recapitulation with a 28-measure lead.

The last element to comment on is the aspect of the text and its political connotation. Lachenmann uses a text by Christopher Caudwell, integrated into the work for a vocal part that both guitarists perform in the first section (bars 55-171). The text, originally in English and translated into German, is an excerpt from the last chapter, titled The Future of Poetry, from the book Illusions and Reality (1937). In this excerpt, marked by a Marxist perspective, it is argued that the bourgeois conception of freedom is truly socially conditioned by the vital circumstances. Despite the use of the text, Lachenmann distances himself from Caudwell’s belief that proletarian art should be the vehicle for the dissemination of the ideas discussed. In fact, while Lachenmann aims to subvert bourgeois listening habits, the composer has always stated that music does not have a political function.

This aspect has been discussed on several occasions. For instance, German musicologist Reinhold Brinkmann considers Lachenmann a politically engaged composer, as he breaks aesthetic taboos and challenges the norms of thought and musical listening. According to Alastair Williams, in Music in Germany since 1968, although Lachenmann is reluctant to align himself with any political ideology, connections to Marxist thought can be found in his music. While, as mentioned, Lachenmann distances himself from Caudwell’s way of exposing bourgeois illusions, he aligns with the English writer in the belief that artistic activity is necessary as a vehicle to achieve this goal.

In Salut für Caudwell, Lachenmann does not choose the text before composing, nor does the idea for the work seemingly originate from it. As Lachenmann himself acknowledges: “I had the feeling that this music was accompanying something: a text, scattered words, or thoughts.”13

Although the text has meaning and connotation, Lachenmann uses it more as a means to achieve a particular sound than for rhetorical purposes. Lachenmann asks that the text be read with a neutral tone, at mezzo-forte, seeking for the voices and instruments to have a uniform sound, with no one exceeding the volume of the others. Additionally, he emphasizes that the rhythm and proper pronunciation must be strict. In fact, he provides a transcription of the entire text in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) in German to facilitate pronunciation.

Finally, the fragmented arrangement of the text, both within the individual lines and between the two guitarists, suggests that the words have more of a sonic intention, like another gesture of the performer-instrument, rather than an impulse of meaning. Moreover, the transcription in the International Phonetic Alphabet would damage the naturalness of the diction, as well as the accentuation of the text. This further supports the idea that the text is purely for sonic purposes.

However, Alastair Williams proposes a meaning for some of the gestures in the composition. For him, for instance, the gestures Lachenmann introduces repetitively and fragmentedly starting from bar 312 (referred to earlier as “of energetic displacement”) evoke gunshots, as a direct reference to the cause of Christopher Caudwell’s death. Caudwell voluntarily enlisted in the army of the Second Spanish Republic to fight against the military coup that sparked the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939. He died in the Battle of Jarama in 1937, at the age of 29.All that has been said leads us to consider Salut für Caudwell as a work that faithfully represents the compositional thought of Helmut Lachenmann. From the need to seek a new sonic path as an element of subversion in relation to the elements of tradition, both guitaristic and Western music in general, from which we can only infer an element of destruction. On the other hand, it also exemplifies the ongoing debate regarding the political question in the composer’s music. Finally, it is undoubted that the work represents a turning point for the instrument, both in terms of interpretation and composition. Lachenmann opens a multitude of new paths to (re)understand the concept of what the guitar means and its performers.

- The first time Lachenmann wrote for guitar was in Air (1968) for large orchestra and solo percussion, where he included a part for electric guitar. ↩︎

- It is important to remember that the guitar is traditionally considered a transposing instrument, meaning that the sounding result is usually an octave lower than what is written in the score. However, Lachenmann, in line with composers of his generation, writes the actual sounding pitch. Therefore, guitarists must finger an octave higher than what is notated. ↩︎

- Bernal, Alberto. Helmut Lachenmann: 1976, 1984 y 2005. Tres estaciones de un espíritu crítico. Radio clásica. 2005 ↩︎

- The term derives from Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète. ↩︎

- Rebhahn, Michael. Nada está conquistado (80 cumpleaños de Helmut Lachenmann). Goethe-Institut. 2015 ↩︎

- Lachenmann, Helmut. Hören ist wehrlos — ohne Hören. Über Möglichkeiten, MusikTexte 10. 1985, 7–16 ↩︎

- Lachenmann, Helmut. Über das Komponieren. MusikTexte 16. 1986, 9–14 ↩︎

- Jiménez Carmona, Susana. Luigi Nono: por una escucha revuelta. Akal Música. 2023 ↩︎

- Dyer, Mark. Helmut Lachenmann’s Salut für Caudwell: An analysis. Tempo 70. 2016. 34-46 ↩︎

- Williams, Alastair. Music in Germany since 1968. Cambridge University Press. 2013 ↩︎

- Chamizo, Mikel. Notas al programa del concierto del dúo Lallement-Marques perteneciente al X ciclo de conciertos de Música Contemporánea. Fundación BBVA en Bilbao, 2019. ↩︎

- Williams, Alastair. Music in Germany since 1968. Pág. 87 ↩︎

- Williams, Alastair. Music in Germany since 1968. Págs. 12,94 ↩︎